![]()

1878 to 1885

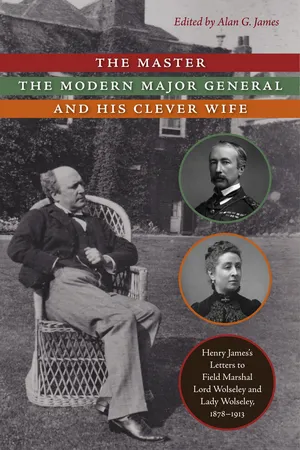

IN THE SUMMER OF 1877 Major General Sir Garnet Wolseley, “supreme master of irregular warfare in an expanding empire” (Lehmann, Model Major General 9), and Lady Wolseley were spending a weekend with friends in Warwickshire. “A showery day,” Wolseley wrote in his diary on Saturday, July 28. “Played tennis in a long unfurnished drawing room. Mr. James an American novelist … joined our party here” (Wolseley Diaries, South Lanarkshire Council Museums, Hamilton, Scotland).

To his mother, James enthusiastically described the occasion, one of his first English country house weekends since arriving in London eight months earlier. He had, he wrote, recently enjoyed “a very pleasant episode of a couple of days at a country house at the Dugdales in Warwickshire, and they were charming.”

It is a glorious old place—an immense park: oaks six hundred years old.1 Browsing deer etc.; the house—quite a ‘great’ one—was full of easy, friendly people; and the combination of the spacious, lounging, the talking-all-day life, the beautiful place, the dinner party each night, the walk to church across such ideal meadow paths …—all this was excellent of its kind. Staying there was Sir Garnet Wolseley, the victor of the Ashantees, a couple of years since, and proprietor of a very charming wife2 with whom I became quite ‘thick.’ (HJL 2:128; 6 Aug. 1877)

Host to James and the Wolseleys was Stratford Dugdale (1828–1882), proprietor of the “great” house, Merevale, and scion of a venerable, landed Warwickshire family. His wife, Alice, whom James had met two months earlier and thought “a nice friendly woman,” belonged to one of England’s “governing families.” Her father was Sir Charles Trevelyan, a former governor of Madras and a social reformer; Lord Macaulay was her uncle; and George Otto Trevelyan, Liberal Party grandee and historian, friend to James and the Wolseleys, her brother.

When James met the Wolseleys, he was plunging “deeply into the study of London,” Gosse observed, “externally and socially, and into the production of literature in which he was now as steadily active as he was elegantly productive” (A&I 25). He had not yet, however, brought out a book or an article, although some of his work published in the United States had been favorably reviewed in England. So his welcome into English society was, Gosse thought, “remarkable,” for “he seemed to have little to give in return for what it offered except his social adaptability, his pleasant and still formal amenity, and his admirable capacity for listening” (26).

Six months later the Wolseleys invited James to dine at their London home. To his brother William, James recounted that agreeable evening.

I also dined one day at Sir Garnet Wolseley’s—amid the usual collections of rich accessories (it is a beautiful old house in Portman Square filled with Queen Anne bric à brac to a degree that quite flattens one out) plain women, gentlemanly men etc. After dinner I was entertained of course (the men were all, I think, army men) with plenty of the densest war-talk.3 Sir Garnet is a very handsome, well-mannered and fascinating little man—with rosy dimples and an eye of steel; an excellent specimen of the cultivated British soldier. But my slight acquaintance is chiefly with his wife, who is pretty, and has the air, the manners, the toilets and the taste, of an American. (HJL 2:149; 28 Jan. 1878)

In the summer of 1878 Prime Minister Disraeli appointed Wolseley governor of Cyprus, which Britain acquired at the Congress of Berlin as part of the settlement of the Russo-Turkish War.

In the year after he met the Wolseleys, James wrote French Poets and Novelists, Daisy Miller, and The Europeans. The autumn of 1879 saw him in Paris, where he finished Hawthorne. There he met, apparently by chance, Lady Wolseley and Frances, then seven years old, who were staying at a hotel in Versailles. He lodged at the Paris hotel where his and the Wolseleys’ friends Andrew Lang and his wife, Leonora, were staying. Being in Paris “is very cheerful and comfortable,” James wrote to his father, “and makes a salubrious break in my London life; … There have been various English people, whom I have had to be more or less preoccupied with—Lady Wolseley the last in order” (HJL 2:257; 11 Oct. 1879).

Seeing James evidently was an agreeable surprise to Lady Wolseley. She described their meeting to her husband, who was then in South Africa, where he had been transferred from Cyprus to deal with a crisis in Zululand. “Mr. James turned up in Paris and went to the Opera with us one night,” she wrote. “He has become quite Frenchified looking” (LW/P 5/71; 1 Oct. 1879). A week later she reported:

Yesterday Mr. James, who I had seen in Paris with the Misses Lawrence4 came down to see us. I was out when he called, so he came back at 6.30 and stayed until 7. There was no train for him til 8, by which time he’d reach Paris at 9, too late for dinner, so I asked him to share my frugal meal, which he accepted and he was most pleasant. He gave me the whole history of Mrs. Ronalds. I will keep the particulars in my mind for you. She is supposed to have been for some years the mistress of the Bey of Tunis.5 I am going to the Comédie Française tomorrow, or Friday, and taking one of F’s governesses with me, and Mr. James is to get our tickets and go with us. (5/8; 8 Oct. 1879)

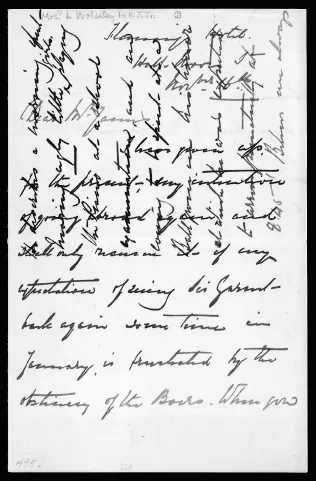

Lady Wolseley returned to London in mid-October. James remained a little longer. A month later, she wrote him the following letter, the only one of hers that has survived.

Fleming’s Hotel | Half-Moon Street | Novbr. 16th |[1879]

Dear Mr. James:

I have given up, for the present, any intention of going abroad again and shall only reassess it if my expectation of seeing Sir Garnet back again some time in January is frustrated by the obstinacy of the Boers. When you come to London,—I think you proposed remaining abroad until December?—I hope you will come and see me, and I write you my plans in hopes of your doing so.

I spent a pleasant three weeks with the Lawrences and go to their brother’s place,6 where I shall find them also, for a couple of days mid-week. Here also (I am writing from a country house in Essex and not from Fleming’s) I am spending a “Saturday til Monday.” One gets spoilt by having one’s entire freedom from society for some months as I had this summer, and I feel now a two days visit the longest I can bear.

I envy you Paris and its surroundings, and “Le Marquis de Villemer.”7 I only nearly put off my return home another day to see it, as it was given the very evening I left Paris. My husband is grousing over his social duties at Pretoria.

He describes a morning spent hearing ugly little girls playing the piano at a school examination, and an evening to be spent at a ball given in his honour at which he was expected to arrive punctually at 8:45. Believe me always sincerely yours

L. Wolseley

MS Houghton Library, Harvard University, bMS Am 1094 (495); reproduced by permission of the Houghton Library and Bay James

James returned to London in late autumn 1879 and sold Washington Square to Cornhill Magazine; it was illustrated by George du Maurier (1834–1896). In Florence in the spring of 1880 he started to write The Portrait of a Lady, which began serialization later in the year.

Wolseley successfully completed his mission to South Africa and returned to London in May 1880. He continued to rise in the military hierarchy, becoming in the next two years quartermaster general and then adjutant general.

After passing the first half of 1881 in Italy, James made his first visit in six years to the United States. While he was there, his mother died, in January 1882, and he stayed on until May. There are no letters from James to the Wolseleys during his stay in the United States, and it appears that he saw little of them after his return. In October he was off once more to France to tour the châteaux of the Loire and the Midi.

Meanwhile, a stunning feat of arms in the Egyptian desert brought Wolseley new honors and even greater popularity. In 1881 a revolt led by Colonel Ahmed Arabi, a nationalist firebrand, had broken out against the khedive. When Arabi’s activities threatened European lives and property, as well as the Suez Canal, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Gladstone decided (reluctantly) to intervene. In the summer of 1882 a small but powerful British army, commanded by Wolseley, was sent to Egypt. The general maneuvered his force skillfully and in September met the rebels at Tel-el-Kebir, between Cairo and Ismalia. There the British destroyed the insurgent army, ending the rebellion. The Tel-el-Kebir campaign may have been warfare on a limited scale against an ill-equipped, non-European enemy, but it was a masterpiece of generalship. The purpose of the expedition was achieved quickly, efficiently, and with few lives lost (few British lives, that is; the rebels suffered frightful casualties). Victory brought a peerage for Sir Garnet, who took the title Baron Wolseley of Cairo and Wolseley, and he was promoted to full general.

As he toured in France, James read press accounts of Wolseley’s triumph in Egypt. He returned to London in late autumn 1882 but did not have an opportunity to see the Wolseleys before he was summoned to the bedside of his father, who died in December, before he reached Boston. After his father’s death, James remained for the next half-year in the United States, settling his father’s affairs and visiting old friends and family. Back in England in August 1883, he began to see the Wolseleys more frequently.

First page and conclusion of Lady Wolseley’s letter to Henry James, 16 November 1879. (By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University [bMS Am 1094 (495)], and Ms. Bay James)

In the summer of 1884 Wolseley was given command of an expedition to rescue his friend and Crimean War comrade General Charles “Chinese” Gordon (1833–1885), who had been sent to the Sudan by the Gladstone government to evacuate Egyptian troops and later was besieged at Khartoum by the Mahdi’s army. Wolseley deployed his force with customary skill but could not reach Khartoum before the dervishes killed Gordon in January 1885. James closely followed Wolseley’s ascent of the Nile and its tragic dénouement. ...