![]()

1 IDENTITY

The following chronicles Cornelia Hahn Oberlander’s life from childhood to her graduation from Harvard University in 1947. It gives an account of her motives as well as the circumstances that have shaped her life, and eventually her practice as a landscape architect. Here, Oberlander’s own words order the narrative. These brief passages speak to her identity: her experiences in Weimar Germany and her mother’s gardening and writing endeavors, her resolve to assimilate and not let the appreciably traumatic events from her past feature disproportionately in her future, and her sheer determination to be a modern landscape architect. These quotations and the ideas they spark also illuminate experiences shared by others regarding gender and the future of the profession. During and immediately after World War II the notion of women working and raising a family was questioned; however, Oberlander was determined to do both. Ultimately it was her experiences at the GSD that nurtured her social convictions and fostered her use of abstraction, her participation in cross-disciplinary collaborations, and her belief in the economic thrift of design. Together these principles formed the poetic pragmatism of her modern landscape architecture.

I’ve made up my mind to adjust myself, discard sentiments and look into the future. — Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, “Reflective Moments,” 1941

Born in Mülheim/Ruhr, in 1921, Oberlander is part of what the historian Walter Laqueur has called “Generation Exodus”: German Jews born between 1914 and 1928 who fled Nazi persecution during the 1930s. Laqueur reveals that this cohort of refugees hailed from different classes, from the very poor to the wealthy, and diverse religious backgrounds; some were practicing Jews while others were members of assimilated families. However, an underlying pattern that they commonly shared was their ability to thrive in their adopted countries. According to Laqueur, age mobilized their success. These refugees, who included Henry Kissinger and Ruth Westheimer, were teenagers and young adults when they escaped. Thus, they were old enough to feel the gravity of their family’s situation but young enough to adapt and survive in their new countries. In fact numerous individuals from this generation, such as Oberlander, made significant contributions to their professions and their newfound communities. Moreover, members of Generation Exodus continued to identify with Weimar Germany. Although they felt the raw sense of loss when they fled their homeland, scores still remember happy childhoods when Germany was a culturally rich, democratic society.

The Weimar period marked a time when modern design and new materials heralded the emergence of a postimperial society and a leveling of social inequities. Oberlander’s family actively participated in this effervescent period of art and design. Her mother attended dance performances at the Bauhaus in Dessau, her father studied Bauhaus prefabricated houses, and her grandparents lived in a house designed by Erich Mendelsohn.1 Jutta, Oberlander’s best friend, lived in Mendelsohn’s Bejach house in Berlin/Steinstücken. Playing there daily she was impressed by the way the structure extended into the landscape with long terraces and perimeter walls that matched the same materials and design of the house, an integration of landscape and architecture that she would seek in her own work. Indeed, Oberlander’s experiences of modern architecture during one of its early evocations in twentieth-century Europe gave voice to her belief that an enlightened life was a modern one, and it propelled her gravitation to modern landscape architecture as a young woman.

The Hahn family’s escape from Nazi Germany was a long and carefully planned process. In 1932, when the National Socialists succeeded in dominating parliament, Oberlander’s parents, Beate and Franz, pledged to each other that they would leave.2 Since 1926 Oberlander’s father, an engineer, had studied scientific management in the United States with the renowned industrial psychologist and engineer Lillian Moller Gilbreth. Beate and Franz agreed that the United States would be their destination. Tragically, on 12 January 1933 Franz Hahn died in an avalanche while skiing in Switzerland. Although his death may have slowed the family’s departure, Beate Hahn was still determined to leave. Now a widow with young children, she kept in close contact with family members abroad and with Franz’s colleagues working in England and the United States. Gilbreth, who had been widowed with eleven children in 1924, was a particularly loyal friend. As Nazi oppression and terror campaigns mounted, Gilbreth visited the Hahns in Germany each year to show her support for Beate and the children.3

While Beate Hahn planned her family’s exodus she attempted to keep things as normal as possible at home in the leafy suburbs of Berlin.4 The Hahn family continued to ski, despite Franz’s accident, as well as skate, swim, and garden together. While seeing a painting of a landscape initially inspired Oberlander’s quest to become a landscape architect, tending her own garden was also a motivator. It was during this time period that Oberlander began to garden extensively, learning precepts and skills about working with natural systems that she would build upon as a landscape architect later in life. Using companion plants, amending soil organically, attracting birds and insects that mitigated pests, and working with plants hardy to a location laid the groundwork for the ecological basis of her practice. It was also during this time that Oberlander developed otosclerosis, abnormal bone growth near the middle ear (repaired in 1967). While the condition gradually impaired her hearing, it sharpened her visual acuity. As vision supplanted sound, she developed a predilection for the world as comprehended by the eye, another aspect that would inform her later work.

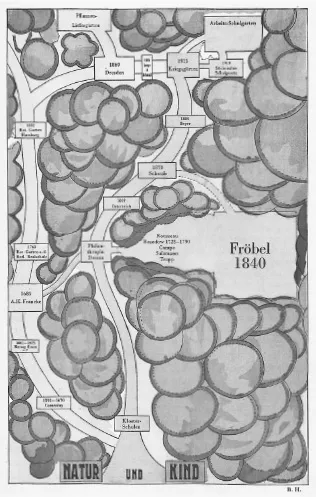

As a professional horticulturalist, Beate Hahn authored several books about gardening with children and how this activity supported their development and education.5 For example her 1935 book Hurra, wir säen und ernten! (Hooray, we sow and harvest!) linked the seasons of the year with activities and songs that children could perform in the garden. Hahn also studied the work of Friedrich Froebel, founder of the original German kindergarten, and she was one of the earliest twentieth-century writers to acknowledge the use of gardens in his schools. Certainly Hahn’s interest in Froebel’s gardens is telling. Froebel sought refuge from an increasingly strict Prussian government by creating a garden culture, the kindergarten, which was based on the maxim: “Come let us live with our children.” For Froebel, the kindergarten provided an idealized world distinct from real-world Prussian oppression — a concept that would have surely appealed to Hahn at the time.6

Oberlander was recycling at a young age. She created her costume by reusing the straw baskets from large Chianti wine bottles, Switzerland, 1934.

Oberlander assisted her mother with the drawings for her books. Her rendering of a diagram entitled “Natur und Kind” (Nature and Child) for Hahn’s 1936 Der Kindergarten ein Garten der Kinder—Ein Gartenbuch für Eltern, Kindergärtnerinnen und alle, die Kinder lieb haben (The kindergarten a children’s garden—A garden book for parents, kindergarten teachers, and everybody who loves children) is an exquisite example of Oberlander’s early exposure to the power of the plan as a conceptual device to communicate ideas. “Natur und Kind” is a plan view of a woodland landscape with paths expressing the passage of time. Along the path, stopping points represent events and people as diverse as Bishop John Amos Comenius, the sixteenth-century Moravian author of The Whole Art of Teaching;7 the nineteenth-century children’s garden advocate Erasmus Schwab; and the development of twentieth-century school gardens in Germany. These individuals and events contributed to the development of children’s gardening and other philanthropic programs in Europe. Froebel, depicted as the largest stopping point on the main path, is a clearing in the woodland landscape.

Plan view rendered by Oberlander for her mother’s book Der Kindergarten ein Garten der Kinder—Ein Gartenbuch für Eltern, Kindergärtnerinnen und alle, die Kinder lieb haben, 1936.

The metaphor of time as a pathway would continue for Beate Hahn. Years later, Oberlander asked her mother how she was able to cope with the rising violence against Jews during these years. Hahn replied, “I envisioned a path, a long straight path with posts on either side. At the end was our new home. I just kept following that path, never straying from it.”8 On 23 November 1938, two weeks after Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), the Hahns joined the nearly 40,000 refugees fleeing Germany that year. Their escape was not without incidence. Fleeing by train they approached the German border and an officer boarded. He bellowed at Beate and her two daughters to get off the train immediately. Fortunately, Oberlander’s uncle, Kurt Hahn, had sent his friend Sir Alexander Lawrence to accompany the Hahns. Lawrence asked the officer why they should get off. Appealing to the officer’s fascist adherence to rules of conduct, Lawrence also added that when attending a conference in Germany he was very impressed by the nation’s lawfulness. While the pair conversed the train started to move. The officer had to jump out of a window and the train continued on its way.9

The Hahns eventually reached the United States in early 1939, and Oberlander spent her first weekend at Lillian Gilbreth’s house in Montclair, New Jersey. Gilbreth took a special interest in Oberlander. Sensing her desire to fit in she decided to treat Oberlander like all the other members of the Gilbreth family and assigned her a household task—washing dishes.10 The Hahns initially moved to New Rochelle, New York, living in a house almost identical to one in a photograph given to Beate by Franz in 1932. While the house matched the picture, Hahn needed a larger property so that she could garden and they soon moved to a farm in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire. There, Oberlander spent her first year helping her mother manage the farm, donating their harvests to the war effort, and that winter partaking in her favorite pastime, skiing.

Oberlander in Berlin, 1938.

In 1940 Gilbreth took Oberlander along to visit her daughter at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. The Olmsted office had designed the campus in 1893, and Gilbreth knew that this women’s college offered degrees in landscape architecture. (By 1938 the Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, founded in 1915 by the architect Henry A. Frost to exclusively educate women, had been made part of Smith College.11) In 1940 Oberlander was accepted into an interdepartmental major in Architecture and Landscape Architecture. This was a critical step in Oberlander’s adjustment to her new life. Smith provided her with academic courses regarding landscape architecture; but the college environment also gave her a place where she could assimilate into American society. In an essay penned in 1941 for English IIIa, Oberlander offers a glimpse of her struggles to adapt, writing, “There are long periods where I don’t think of being a foreigner. But then again, a sudden little incident might shake me, throw me back and make me meditate again. It happens sometimes when I go to a house of a friend’s. I often have to tell of our escape. I am made to feel like a movie and I don’t feel real: I suddenly notice that there is a high wall between me and my hosts, which neither of us can cross. I feel as if I am in borrowed shoes which are much too large for me and no one can make them fit.”12

During the summer and school breaks from Smith College, Oberlander continued to work on her mother’s farm in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, 1941.

While the instructor’s comments on her paper indicate a greater concern for Oberlander’s spelling rather than the story being told, the essay is a poetic testament to her struggles. Her conclusion is equally revealing. At the end of the essay, Oberlander resolved, “I am determined not to give up. I’ve made up my mind to adjust myself, discard sentiments and look into the future and learn and understand the demands of America.”13 But as she soon discovered, these demands were not always in keeping with her own views, particularly as they regarded her future as a female landscape architect.

If you ...