![]()

1

Angry(-ish) Young(-ish) Men: Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and Absolute Beginners

The year 1958 was pivotal in the development of British youth culture and in post-war writing about it. In addition to the publication of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, 1958 saw the appearance of Keith Waterhouse’s hugely popular Billy Liar (made into a film starring Tom Courtenay and Julie Christie a scarce five years later) and Ernest Ryman’s sensational novel Teddy Boy, which contrasted the rehabilitative effects of a reform school on juvenile delinquents with the downward spiral into deviance and violent criminality of the Teddy boy living outside the reform system. The year also yielded the first bona fide rock ‘n’ roll hit song to come out of the UK, in Cliff Richard’s ‘Move It’, and the dance craze/song ‘The Stroll’ – which would already belong to the distant past by 1971 when Led Zeppelin sang that ‘It’s been a long time / Since I did the Stroll.’ It’s the year during which Colin MacInnes’ Absolute Beginners was written and in which it was set, though the book itself did not appear until the following year. Finally, and perhaps most importantly of all, 1958 is the year of the first post-war race riots in England, starting in Nottingham and the Notting Hill and Notting Dale sections of London at the very end of August.

In this chapter, we will see how Sillitoe and MacInnes think about the emergent fact of truly distinct youth cultures. We’ll also see how they use those cultures to think with, approaching a heady mix of issues including masculinity, sex and sexuality, class, violence, the legacy of the war and above all race. Along the way, we’ll encounter the first true post-war youth-cultural group, the Teddy boys, along with early prototypes of the mods and rockers who will usurp the Teds’ status as folk devils du jour as the 1950s give way to the 1960s. Contrasting how these two near-contemporaneous novels handle these youth cultures illuminates surprisingly disparate attitudes and sets the stage for the next chapter’s consideration of perhaps the most self-contradictory post-war novel of all, A Clockwork Orange. Ultimately, though, we will see how profoundly conservative both Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and Absolute Beginners end up being – again, in anticipation of Burgess’s arch-conservative novel.

One of the key differences between the two novels is their temporal orientation: Saturday Night and Sunday Morning faces backwards, presenting a 1958 that is still well and truly in the clutches of the 1930s, while Absolute Beginners gives us a 1958 that is in a desperate rush to leave the past behind and to arrive in the future now, if not sooner. They present complex temporalities that overlap, conflict and shift arbitrarily depending on which aspect we focus on. The novels’ divergent treatment of Teddy boys illustrates this divergence in temporal orientation.

That divergence has its origins in Teddy boys themselves. As ‘Britain’s first youth subculture’ (Bell 3), Teddy boys articulated a complicated cultural moment. For many members of the British public, the Teds presented a menacing view of the future arriving just a bit too early for comfort. Life had just begun to return to normal after the end of rationing in 1954 and here already were people chafing under that normalcy. Refusing to go back to pre-war social distinctions, the Teds mobilized their unprecedented prosperity – achieved through full employment, but also through black market economies trading on goods ‘liberated’ from American PX stores still in England – to challenge the old social hierarchies. They took advantage of relaxed curfew laws and increased urban mobility to assert their agency in the streets, flaunted their affluence and embraced aspects of American culture such as African-American music (though preferably played by whites). ‘Usurping the Savile Row-sponsored neo-Edwardian style of young aristocrats in the late 1940s, “Teddy” style also combined the fashion of wartime “make-do-and-mend” customization, “spiv” gangsters, American “zoot” and East End “cosh boy” youth gangs’ (Bell 3). They seemed harbingers of a brave new world, one marked by swagger, brash confidence and a determination to take full advantage of the privileges won for them in the war.

And yet the Teds were not by any means only a forward-looking group. The moral panic they provoked had as much to do with their invocation of a past that was gone for good as it did with a heady vision of the future. The two are but sides of the same coin, to be sure: The edgy threat of Teddy boy futurity gains heft in its contrast with an idyllic past that can never again be. On this point, Bell goes on to note that the Teddy boys’ ‘complex postwar reaction to austerity, rationing and National Service’ was ‘measured against a nostalgic vision of the English past’ (3). This ‘nostalgic vision’ is key; the Teds sought not only to assert their agency against a bewilderingly changed world, but also to anchor their identities in pre-First World War certainties. The ‘Edwardian’ aspect of their dress did not just assert affluence in its use of extravagant quantities of fabric and its flamboyant colours; it also anchored the Teds in the warm glow of Britain’s last time of self-assurance – the summer of 1914. Sartorially at least, the Teds rejected both world wars, the ‘roaring twenties’ and the ‘dirty thirties’, reaching back to the days of their grandparents’ youth for an historical correlative to their sense of present possibility. Contrary to what many thought at the time, and what most commentators since have continued to assert, the Teds sought not only to break with the past, but also to anchor their claims to authenticity in a nostalgic vision of the summer of 1914. In doing so, the Teds introduced the problems that would dog youth cultures for the rest of the century: Crises of masculinity, class and national identity provoked by Britain’s changing place on the world stage; shifts in women’s status and rights; massive immigration; post-war prosperity; and the horrors of the Holocaust. By asserting allegiance to Edwardian values in their choice of clothes, Teddy boys also declared a clear, elemental model of masculinity and national identity.

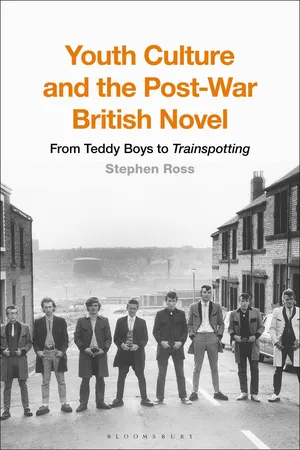

The Teddy boy phenomenon was far from exclusively masculine, though its afterlife in fiction and mass media alike might well lead one to think so. As with all the youth-cultural groups of the 1950s and 1960s, the male core was attended by a strong and vibrant female auxiliary. Teddy boys were joined by Teddy girls, or ‘Judies’, who ran their own gangs and indulged in the same vices and behaviours as their male counterparts. Ken Russell’s series of photographs entitled ‘The Last of the Teddy girls’ provides the most vivid document of this group, recording these rebellious young women in poses of defiance, swagger and arrogance truly befitting the Teddy brand. As these images illustrate, Teddy girls dressed like Teddy boys, came from the same class background and neighbourhoods as Teddy boys and fought just as viciously as well. Though they ran in smaller numbers and provoked much less of a moral panic than Teddy boys, they were indeed a force to be reckoned with.

FIGURE 1.1Teddy boys and Teddy girls, or ‘Judies’, 1955. (Photo by Popperfoto/Getty Images.)

Tellingly, though, this clearest record is visual – it exists in a series of photographs and has no textual equivalent. Indeed, none of the women in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Absolute Beginners or even Ryman’s Teddy Boy is presented as a Judy. Nor are there any readily identifiable female mods or rockers, even in MacInnes’s cutting-edge depiction of English youth culture. As I discussed in the introduction, the problems surrounding women’s exclusion from fictional representations of post-war youth cultures – at its most acute in the 1950s and 1960s – are complex. Simply put, in the 1950s, such subcultural young women seem not to have captured either the popular imagination or the writerly fancy as their male counterparts did: To put it colloquially, they were wild in the streets but nowhere in the sheets (of paper). Whatever the reasons for this disparity, the fact remains that while up-and-coming writers such as Sillitoe and MacInnes were thinking with and about the emergent youth cultures of their day, women writers such as Iris Murdoch, Doris Lessing and Muriel Spark were exploring different topics.

These historical and cultural complexities mean that the Teddy boy functions as a much more complex figure than most critics have thus far allowed. Not simply the product of relatively lawless childhoods during which they ‘had spent the most important years of their childhood during the war, with fathers away in the Forces and mothers often out on war work’ (Elloway in Waterhouse 204–5), nor simply thuggish young men with money, time, mobility and a heady sense of agency marauding the streets, the Teds in fact articulated a dense knot of conflicted temporalities with complicated ideological significations. The differences in how contemporary writers such as Sillitoe and MacInnes think with and about this figure are thus profoundly interesting.

On one side of the divide is Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Sillitoe’s novel articulates a vision of the Teddy boy as an authentic representative of traditional English masculinity, individualism and agency. The novel appears in 1958, but presents a vision of life in industrial Nottingham that is riven with nostalgic disjunctions, glaring blindspots and a profoundly conservative outlook. It is nostalgic about the war years, and grudgingly optimistic about post-war prosperity (as measured against the terrible years of the 1930s), but ultimately uninvested in the revolutionary potential of youth culture despite having a Teddy boy as its main character. Sillitoe teases the liberatory anarchic potential of the Teddy boy, only to yank away any promise it may hold at the first sign of trouble. Most crucially, the novel presents a vision of post-war Nottingham that nourishes a National Front fantasy of the harmonious working-class city: Sillitoe’s 1950s Nottingham has virtually no black people in it, despite the fact that tens of thousands of West Indian immigrants had been arriving in England throughout the 1950s.

Let’s begin with Arthur Seaton, Sillitoe’s Teddy boy protagonist. Thus far, critics have either ignored Arthur’s Ted credibility or else vacillated about its authenticity. Of the very few critics who have considered Arthur’s nomination as a Teddy boy worthy of critical commentary, Ian Brookes is exemplary, insisting that ‘Arthur is not a Teddy Boy but he is twice identified as one’ (Brookes 21). He offers no justification for his reading. Nick Bentley ultimately withholds his verdict. Likewise insisting that Arthur cannot ‘be said to be part of a subculture such as the Teddy boys’ (Bentley 2010, 24) and that ‘Arthur is not a Teddy boy in the sense of his belonging to a subculture’ (25), Bentley allows that ‘Arthur Seaton’s relationship with his clothing matches [that of …] Teddy boy subculture’ (26) and ‘the suits Arthur owns are of the style worn by the Teddy boys’ (26). The logic behind these repudiations eludes me, I confess. Brookes and Bentley both seem to be marking a distinction without a difference.

That Arthur does not run with a gang of other Teds seems a wholly inadequate reason to discount the fact that he is explicitly presented as a Teddy boy. He is repeatedly called a Teddy boy, first by the woman he throws up on in the novel’s famous opening scene (‘“Looks like one of them Teddy boys, allus making trouble”’ [16]) and then by a sergeant-major during his two weeks’ national service (‘“You’re a soldier now, not a Teddy-boy”’ [138]). His clothing is uniformly characterized as being in the Teddy boy style, from the ‘teddy-suit’ he prefers ‘for going out in at night’ (Sillitoe 28), to the closet full of flashy, expensive items in which he has invested a huge amount of money:

[He] selected a suit from a line of hangers. Brown paper protected them from dust, and he stood for some minutes in the cold, digging his hands into pockets and turning back lapels, sampling the good hundred pounds’ worth of property hanging from an iron-bar. These were his riches, and he told himself that money paid-out on clothes was a sensible investment because it made him feel good as well as look good. (66)

Later still, he surveys ‘his row of suits, trousers, sports jackets, shirts, all suspended in colorful drapes and designs, good-quality tailor-mades, a couple of hundred quids’ worth, a fabulous wardrobe of which he was proud because it had cost him so much labour’ (Sillitoe 169). Even his girlfriend Doreen takes note, in tones of admiration and suspicion alike (is this the kind of man you marry?):

‘Are all them clo’es yourn?’

‘Just a few rags’, he said.

She sat up straight, hands in her lap. ‘They look better than rags to me. They must have cost you a pretty penny.’ (185)

Even Arthur’s footwear fits the Teddy boy mould, corresponding to the crepe-soled ‘brothel-creepers’ favoured for dances, fights and loitering in the streets (66). Moreover, Arthur wears his ‘fair hair short on top and weighed-down with undue length at the back[, sending] out a whiff of hair cream’ (66), in the signature Teddy boy style of the quiff up front and the duck’s arse or duck-tail in back. If Arthur is not a Teddy boy, he sure as hell looks like one.

And yet, Bentley is not entirely wrong to suspect that there is something missing – something inauthentic – in Arthur’s Teddy boy credentials. He lacks some key features of Teddy boy comportment: He is not gratuitously violent, he does not loiter in the streets, he carries no weapons, and he does not participate in any criminal activity – at least not of the sort typically associated with Teds (e.g. black marketeering and theft). We know nothing at all of his musical preferences, let alone whether they are consistent with the Ted affection for ‘black gospel and blues […] fused with white country and western’ (Hebdige 49), whether he dances the Teddy boy signature dance, ‘The Creep’ or whether he shares the growing Teddy boy antipathy towards the flood of immigrants entering the UK in the 1950s. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and it may even be the case that it’s the Teddy boy’s ambiguity, his unknown quantity and the new possibilities he embodies that make him such a flexible figure for Sillitoe to use in his navigation of emerging realities after the war. In what follows, I show that Sillitoe recognized these possibilities in both cultural and narrative terms, and seized his chance to use the Teddy boy as a figure for working through a range of anxieties about masculinity and race.

The question of Arthur’s attitudes toward race is especially poignant, since it points to Sillitoe’s particular take on the Teddy boy, and thus to the novel’s larger politics. In particular, the novel’s racial politics are critical to any understanding of it as a key cultural document of 1950s England. To get there, though, we must first lay the groundwork of understanding Arthur’s masculinity and his politics. Put simply, Arthur is very clearly an ‘angry young man’, with a distinct impulse towards violence. He is an open misogynist and latently violent anarchist, though only in a vulgar sense: He lacks the coherent political or ideological awareness of the genuine anarchist. In both his misogyny and his anarchy, Arthur betrays Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’s temporal displacement from its contemporary moment in the 1950s, anchoring Sillitoe’s view of youth culture in a profoundly conservative direction.

Arthur’s masculinity is of central importance. Sillitoe uses the figure of the anarchic, virile, swaggering Teddy boy to interrogate some of the institutions associated with traditional British culture, perhaps chief among them marriage. The figure of the Teddy boy articulated a whole range of possibilities, particularly with regard to sexual liberty and sexual relationships. In its capacity as a folk devil, the Ted presented a clear and present danger to the social norms embodied i...