![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Cities, Puppets, and Identity

Within the walls of Asiatique on the Riverfront, an evening shopping and entertainment destination for tourists and locals in Bangkok, sits an unassuming Thai man who bills himself as “Manop the Puppet” (Figure 1.1). He sits on a short stool and holds a puppet on his lap. There are several other puppets lying on the ground. Off to a side there is a sign that declares he is “the best street performer in Thailand.” Manop the Puppet sits with a small grayish-blue muppet-style robot on his lap, who wiggles his electronic eyebrows as he sings. A small crowd, taking a break from shopping or eating, gathers around to watch. The street is really a pedestrian walk lined with shops, bars, and restaurants creating an upscale night market. The puppet’s recorded songs switch from Thai to English, or Japanese, as appropriate to the audience gathering around; the man’s own voice is not heard. People laugh and applaud, children dance, couples pose for photos, and sometimes people deposit money in a small tip jar sitting on the ground in front of Manop. This simple performance articulates complex local and global Southeast Asian identities as expressed through relationships between city spaces and puppet performances.

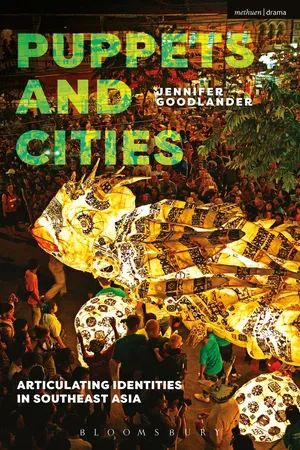

FIGURE 1.1“Manop the Puppet” at Asiatique on the Riverfront, Bangkok, Thailand. Photo by the author.

The Asiatique on the Riverfront opened in 2012 on the shore of the Chao Phraya River in Bangkok’s Bang Kho Laem district. The location and style of Asiatique strives to recall past glories mixed with global aspirations. The complex, which includes over 1,500 shops and more than forty international restaurants, sits at the prior location of the East Asiatic Company—a pier constructed by King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) at the beginning of the twentieth century in order to fend off possible colonization by European countries and to raise the status of Thailand. According to the district’s website, the “pier signaled the beginning of international trade between the Kingdom of Siam (the former name of Thailand) and European nations and was the key to Siam maintaining the sovereignty and independence it enjoys to this day” (Asiatique website). The shops and restaurants sell a mix of Thai “traditional” goods, such as textiles, spices, and small dolls dressed in traditional clothes, together with many international brands and foods.

Manop the Puppet reflects the different values expressed through the spaces of Asiatique. On one hand his performance harkens to the past—it is a simple street performance with several puppets and props. On the other hand, his performance relies on technology for light, amplification, and sound. His main puppet is a large blue-and-silver robot with “R-2” emblazoned across its chest, wearing blue jean shorts. The puppet manipulation uses both strings and robotics to delight the audience with songs, jokes, and dance. The puppet’s features and clothing do not suggest a particular Asian or Thai identity, but through song he moves freely between cultures and languages. The Lionel Richie ballad “Say You, Say Me” drew audiences from many different nationalities, who laughed and cheered.

Asiatique is a modern reconstruction of a glorious Thai past; a crossroads of culture located on a former location of trade and commerce. The puppet performance is the “best” in Thailand, but little or nothing of his performance identifies it as “Thai.” The man operating the puppet is Asian, but he wears black jeans and a black long-sleeved shirt. The man and his puppet would be just as likely to be seen in New York, London, or Berlin, as in Bangkok. The performance and its place demonstrate how the complexity of identity is articulated through interactions of puppet, bodies, place, and audience. The space intentionally invokes tradition but the modern bodies of the performer and audience suggest an intermingling of local and global. The puppet serves as a signifier of all these things—he looks like a modern robot but uses both traditional strings and electronics for animation.

This book addresses how puppetry complements and combines with urban spaces to articulate present and future individual, cultural, and national identities. I provide crucial insight into the dialectical relationships between traditional and contemporary performing arts as creative social agents within systems of economics, politics, and community formation in Southeast Asian cities. I am interested in not only “how places of performance generate social and cultural meanings of their own which in turn help structure the meaning of the entire theatre experience” (Carlson 1989: 2), but also in how city spaces work with performances to do the work of theatre, which, in turn, reflects and informs social interactions and community. As Jill Dolan writes, “live performance provides a place where people come together, embodied and passionate, to share experiences of meaning making and imagination that can describe or capture fleeting intimations of a better world” (2005: 2). I believe that most of the intersections of space, people, and performance described in this book are part of larger projects and feelings in Southeast Asia to work toward improvement. Tradition, modernity, globalization, and a celebration of the local are all enacted in order to better negotiate the past and look with hope toward the future of the region.1

Theatre scholar Claudia Orenstein declares “We are living in a puppet moment,” because the current global society “habituates us to see things as a means of satisfying our desires, expressing our personalities, and somehow completing us—things as an essential extension of ourselves (Posner, Orenstein, and Bell 2014: 2). In Southeast Asia puppetry is one of the oldest performance genres and is linked to religion, politics, and popular entertainment. UNESCO has designated traditional puppetry in several Southeast Asian nations to be “Intangible Cultural Heritages,” adding to its economic and political relevance, but complicating issues of ownership, preservation versus innovation, and transmission. Contemporary or new forms of puppetry are used in development projects and are often combined with traditional dance and theatre to create new hybrid performances. Puppets as material objects require a revised understanding of performance and materiality within different social structures. Puppets parade in street fairs, tour in international festivals, and enact religious rituals; they are talked about and presented in social media, and are also displayed in museums and commoditized as tourist objects. Puppets perform and circulate as things that articulate identities locally and globally.

Nations in Southeast Asia have gone through a period of rapid change within the last century as they have grappled with independence, modernization, and changing political landscapes. Governments, alongside citizens, strive to balance progress with the need to articulate identities that resonate with the precolonial past and look toward the future. The regional focus and effort to put contemporary and traditional performance practices into meaningful dialogue makes this study unique. Most research on Southeast Asian arts and cultures focuses on a single country, even though there are clear connections between the artistic forms that can be traced through their iconography, social uses, stories, and histories. Theatre scholar Glenn Odom offers that there is a direct link between society’s perceptions of identity and theories of acting and approaches to theatre (2017: 155). The puppet is not only a type of actor, but also an aesthetic object manipulated in performance by a human, or mechanical, actor, but the puppet in performance or on display likewise offers insight into identity. I examine various puppet performances to interrogate how various nodes of tradition, community, technology, urbanity, globalization, and modernity interact, clash, and consolidate to create and reify identities in Southeast Asia.

The city as performance space

Cities, recognized as key nodes in networks of local, regional, and global identity, are central to this project; by 2020 the majority of Asian citizens will live in urban areas. Bangkok, Jakarta, Bandung, Kuala Lumpur, Yangon, Phnom Penh, and others serve as large-scale testing grounds for the reinvention of tradition and the questioning of cultural and national identities. Discourses regarding traditional performance often situate art within the villages, or disregard space as an important part of the meaning-making process of the performance. Likewise, traditional and contemporary performances are often segregated and the interrelationships between artists and audiences are frequently overlooked. Cities as sites for global flows, economic growth, and cultural communities have been repeatedly cited as crucial for Southeast Asian development; the performing arts offer hubs for expressing and enacting these goals. The city in Southeast Asia functions as the cultural, political, and economic center for a growing middle class occupied with formulating local and global identities. Social media connects these two spheres as artists promote their work and communicate across borders; besides, it allows public interaction with fans. These various elements compel a rethinking of performance in relation to identity in Southeast Asian cities as productive agents of public/private spaces, economic reform and development, heritage, and transnational networks.

Cities in Southeast Asia are both part of complex international urban trends and unique entities onto themselves. T. G. McGee traces the development of cities in Southeast Asia as originating as hubs of spiritual practices, such as Angkor Thom, or as centers of trade like Malacca. As contact with the West developed from the sixteenth century on, cities became more important as communication and trade network foci. Most key cities had access to the sea, housed important foreign institutions such as banks, and linked Southeast Asia to European economic systems. The relationship between Southeast Asia and the West through these cities intensified at the beginning of the twentieth century when most of the region was under colonial rule. Throughout their history, these cities have been both places of primary contact with outsiders, but also places where dynamic cultures and identities have developed.

The city in Southeast Asia is quite different in character and function from other cities around the globe. Cities in Western Europe and the United States grew in part as a result of industrialization—larger populations of people were needed to manufacture goods. In Southeast Asia, the dependence on foreign trade and governance resulted in jobs being primarily within the tertiary sector—retail, administration, and so on. McGee asserts that this focus on growth within the tertiary sector resulted in an “unhealthy” trend. The lack of industry meant that even though many people were migrating to the cities in hopes of finding opportunity, there was a lack of jobs. “The proliferation of petty traders, pedicab drivers, footpath astrologers, trinket vendors, and food sellers in the colonial city was not a reflection of a growing demand, but simply the result of employment opportunities not growing at a rate fast enough to absorb city population” (McGee 1967: 58). Population growth consisted of people moving from rural areas, natural growth, and migration from other parts of Asia and the world. In some cities there are many foreigners residing or visiting, which influences the character of the city and how it articulates identity. Various cities have large populations of ethnic Indians or Chinese who, even though they have been there sometimes for generations, often retain many aspects of their own heritage and identity. Artists working in urban spaces must think about how to address these diverse audiences.

Cities in Southeast Asia must overcome many challenges. Poverty and transportation are two of the most immediate. Recent figures, published by Southeast Asia Globe, demonstrate that large percentages of the population in the region’s cities reside in slums. In 2014, slum population ranged from 20 to 60 percent of the total urban population. This is while the urban population in relation to the total population has risen to be about 30–60 percent of the total population in 2014, with projected growth in the cities to be around 70 percent of the total population in most countries by 2050. The urban geography of most of these cities consists of overcrowded shanty towns pushed up against tall skyscrapers. This dynamic worsens when coupled with problems of clean water, sanitation, flooding, and social problems of crime, prostitution, poor education, and illegal and unsafe housing. In 2015 I visited some of the slums of Jakarta, and the residents in one shanty town complained that their situation was even more precarious because the Indonesian government would sometimes, and without warning, bulldoze settlements to make way for new construction. In spite of these challenges, cities are thriving and middle- and upper-class populations are growing. Cities remain the center of politics, culture, education, and opportunity for the people of Southeast Asia. Tradition, modernity, local, and global all mix to make these cities vibrant places that reflect the complex identities of Southeast Asians.

Puppet performances and displays often address both the problems and triumphs of the city through a combination of heritage and development as part of larger urban planning initiatives throughout the region. Puppetry offers a place to expose the different layers of identity inherent within the cities—“Cultural layering is a common attribute of most Asian cities. All these different layers are significant, since they reveal stories about stages in spatial production and societies” (Martokusumo 2011: 182). This book uncovers those layers through examining the interactions between puppets, people, and urban spaces. Place, especially place in a city, becomes part of one’s identity—“The sense of one’s historical position and place in time is based on historical places, whether they are in the form of individual buildings, entire cities, or the countries in which they are located” (Martokusumo 2011: 182). Space offers people a means to engage with their sense of history and how the past and future relate. “Performance can help renegotiate the urban archive, to build the city, and to change it” (Hopkins, Orr, and Solga 2009: 6).

The definition of city around Southeast Asia varies—by global standards only Manila in the Philippines is considered a mega-city by the UN—but others argue that official numbers are difficult to come by in the region and that Bangkok, Jakarta, and Ho Chi Minh City ought to be considered mega-cities (Sheng 2013: 147). In this book the size of the cities covered varies greatly, because some countries like Brunei have very small populations while other cities like Luang Prabang, Laos PDR and Siem Reap, Cambodia, are smallish in size, but remain important economic and heritage centers. Throughout this book I argue that the city in Southeast Asia presents a particular set of cultural values, institutions, and ways of being. Cities are where Southeast Asia is most global—that is, people, ideas, and economies intersect in various ways with “outside” worlds. It is also the space where Southeast Asia strives to best articulate its identity to the world and to its own people.

For me the city is not just a place but an object like the puppet. It lives and moves, but never totally on its own. The city and puppet both depend on human animation, but they are a particular kind of object that dictates and controls its movements. Cities and puppets interact with humans to generate meanings and to negotiate identities. Performance studies scholars often examine “how cities are produced and performed” (Martin 2014: 10). I do not interrogate the city as a performed entity, but rather consider puppets, cities, and people together within the production of Southeast Asian identities.

Puppetry, heritage, and identity

Identity is an important concept for understanding Southeast Asia in the current moment. It is linked to economics, nationhood, security, culture—it is the formation of a dynamic and multifaceted “imagined community” that reaches from specific spaces and peoples to cities, nations, regions, the world, and into virtual spaces. Identity belongs both to individuals and to society. It incorporates religion, ethnicity, class, education, gender, and age. Identity is not “just there, it must always be established.” It is an active process within interactions and institutions—it is not something that just “is”—we make our identity; identities are made as ongoing and are never complete (Jenkins 1996: 4). For this book I look at identity in Southeast Asia as a product of both tradition and modernity; I will draw from and complicate different social and political conceptions of identity.

Key notions relating to Southeast Asian identities are diversity, heritage, and nationalism. Numerous books, websites, and even the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) describe ethnic diversity as a defining feature. Beyond national identities there are hundreds of distinct ethnic groups with individual languages and customs that often extend beyond national boundaries. There are also significant populations of ethnic Chinese and Tamil (from India) people in Southeast Asia who have migrated throughout its history. Additionally, Southeast Asia has many different religions, environments, and geographies. Southeast Asia has enjoyed multiple arrangements of exchange with countries from all over the world and experienced its own shifting borders. “Scholars have characterized such territorial arrangements as akin to the concept of a mandala, a Sanskrit term, which used in this way symbolizes the waxing and waning of territories and group allegiances in the absence of firm boundaries” (Shaw 2009: 2). During the twentieth century most countries in Southeast Asia, except for Thailand, were colonized by European countries and the United States, which has added traces of Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and American languages and cultures to the mix. Today, China, Japan, and Korea influence the region’s politics, fashion, and popular culture. The Middle East is becoming more important to expressions of Muslim identity in the region through the sponsorship of religious schools, the spread of Arabic, and more Southeast Asians going on Hajj and wearing headscarves.

Within this great mosaic of diversity, countries are using tradition and heritage to express national identities both a...