![]()

1

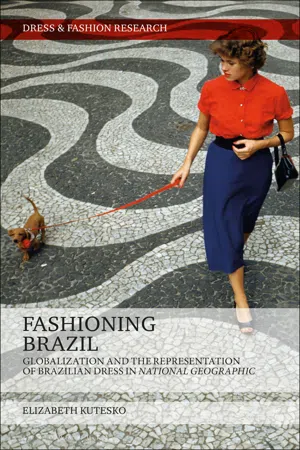

Introduction: Fashioning Brazil and Brazilian Self-Fashioning

In February 2014, four months ahead of the World Cup which commenced on June 12, the Brazilian tourism board Embratur requested that a pair of limited edition T-shirts produced by German multinational Adidas be discontinued. The two offending articles were a yellow T-shirt, which displayed a curvaceous brunette wearing a tiny bikini on Copacabana beach (identifiable by the imposing Pão de Açúcar in the background) beneath the words “Lookin’ to Score,” and its green companion, which presented an upside-down thong bikini bottom encased within a heart, amid the slogan “I love Brazil.” Embratur argued that the T-shirts celebrated a stereotypical Brazilian sensuality, which touched upon the host nation’s problematic reputation as a destination for sexual tourism, and presumably bore little relation to the multifaceted image of Brazil that then president Dilma Rousseff (in office from 2011 to 2016) and her administration were keen to project to an international audience ahead of the games. This revealing altercation is but one example of how the Western fashion industry has capitalized on outsider stereotypes of tropical Rio de Janeiro for its own commercial gain, further to the very real and emotional insider reactions that they provoke within Brazil, whose local populace does not straightforwardly recognize such categorizations as part of their own lived experience of dress, body, and identity.

This book aims to present a more holistic view of how dress and fashion in Brazil have been created, worn, displayed, viewed, and represented over the last one hundred years. It examines how the representation of Brazilian dress in National Geographic has been inextricably linked to culture, identity construction, the interconnected experience of globalization—as it has occurred in multiple and differentiated ways—and the shared histories of Brazil from inside and outside. As a popular “scientific” and educational journal, National Geographic, since it was established in 1888, has played a key role in imagining the world at large. It has divided and labeled that world into areas of greater or lesser importance, often using dress as a vehicle for national identity to be articulated and realized through an outsider gaze. Yet simultaneously, the magazine tells multiple insider stories, about how global subjects have used dress to understand and negotiate their place within the world, expressing local, national, and transnational identities through their personal style and clothing choices. National Geographic is a multilayered resource then, which reveals the deeper connections between different people and places on the map, as well as the power relations that underpin them. It provides a revealing lens—yet to be seriously examined by fashion historians—through which to grapple with the nuances and complexities of dress as an embodied cultural practice, as well as the sensory and affective capacities of its representation that are communicated to the viewer through the pages of the magazine. Anne Hollander developed the idea that fashion only exists through visual media, highlighting the reciprocal and mutually exclusive relationship between the projection of ourselves to the outside world through dress, and the “constant reference of its interpretation” that an imaged world reflects to us (1993: 350). While a global history of fashion is in the process of being pieced together, that dress scholarship to date has neglected to engage with National Geographic can still be understood as part of a larger scholarly tendency to privilege inquiries into Western high fashion. This book bridges a gap between existing scholarship on National Geographic—that has tended to view representations in the magazine as essentializing local cultures—and contemporary academic debate concerning non-Western dress and fashion, which strives to capture the complex history of cross-cultural contact as ideas and inspirations are appropriated from across the globe. In writing of transnational encounter and exchange, I move beyond dichotomous understandings of the power relationships between National Geographic and Brazilian subjects to uncover the complex dynamics of dress as an embodied practice of performing culture.

By turning sustained attention to an underexplored region of fashion production, this book uses National Geographic to broaden our definition of what fashion is within a global context, while proposing a methodology with which to study it. My analysis does not simply apply Western fashion theory to a Brazilian context, but uses Brazilian scholars to contextualize and extend debates on the complex realities of dress and fashion practices in Brazil that have been documented by National Geographic’s vivid gaze over the last 125 years. While I draw upon Brazilian fashion scholarship throughout this book—an important and growing area of research, demonstrated by the work of Katia Castilho and Carol Garcia (2001), Nizia Villaça (2005), Rita Andrade (2005), Valeria Brandini (2009), João Braga and Luís André do Prado (2011), Maria Claudia Bonadio (2014), and Kelly Mohs Gage (2016)—my decision to use five Brazilian cultural theorists to frame the analysis of each chapter is motivated by a desire to open out the key debates on globalization, as well as the relationship between the local and the global, in a more interdisciplinary and unconventional way. Despite constituting a fascinating resource for the fashion historian, National Geographic is not a fashion magazine, nor is it predominantly read by a fashion audience. It is therefore more fitting to draw upon the work of Brazilian cultural theorists Oswald de Andrade (1928), Robert Stam (1998), Silviano Santiago (2001), Roberto Schwarz (1992), and Renato Ortiz (2000), who are not primarily concerned with dress or fashion but nevertheless touch upon these interrelated subjects within their writing.1

Definitions

It is important to outline from the outset the terminology that I use to describe and analyze various dress practices in Brazil. The most widely used term throughout this book is dress, in accordance with anthropologists Joanne B. Eicher and Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins’s understanding of it as “an assemblage of body modifications and/or supplements” (1995: 7). This encompassing definition considers the material properties and expressive capabilities of all types and styles of clothing or garments worn throughout the world. I prefer the term dress to clothing or garment since it extends beyond single or several items covering the body, to acknowledge the numerous acts and products used on the body, including makeup, hairstyle, piercing, scarification, body paint, tattoos, and perfume. Dress is not simply cloth, but a multisensory system of communication, whose many meanings are not fixed but continually informed and to an extent, even performed, through both wearing and representation. I avoid the highly problematic term costume within an everyday context, except when describing carnival or theatrical attire. I also define fashion within an expansive framework, as the demonstration of change and flux within any dress practices, and an additional value that is attached to clothing and its visual representation to entice consumers (Arnold 2009; Kawamura 2011). Fashion can be fast and throwaway street-style, but also rarefied and elite haute couture. It exists in numerous locations across the globe—a potent reminder that challenges the myth that fashion is solely a Western phenomenon, intrinsically connected to industrialization, modernization, and capitalism, which is passively adopted by non-Western cultures as they become Westernized. In retaining the terms Western and non-Western throughout this book, I hope to problematize them from within, demonstrating that they are imaginary constructs, which are brought into sharper focus by examining the case study of Brazilian dress practices. My analysis seeks to develop a globally inclusive and expansive definition of fashion, which emphasizes non-Eurocentric narratives of cultural and sartorial exchange, as well as the multiplicity of fashion systems. Jennifer Craik (1993), Joanne B. Eicher (1995), Karen Tranberg Hansen (2000), Leslie Rabine (2002), Sandra Niesson (2003), Margaret Maynard (2004), Susan Kaiser (2012), and Sarah Cheang (2013) are but some of the scholars who have challenged the perennial distinctions drawn between Western fashion, perceived to be fluid and shifting, and purportedly non-Western dress, misunderstood as static and backward-looking. Their work has highlighted the vibrant and dynamic fashion systems, both macro and micro, that exist and interact across the globe, giving rise to the interconnected processes of mixing, fragmentation, syncretism, multiplication, creolization, and hybridity. Hybridity is an important term that frames my analysis throughout. As Néstor Garcia Canclini has articulated, “No identities [are] describable as self-contained and ahistorical essences” (1995: xxvii); while material objects may have originated in a specific area or location, due to the forces of globalization they are no longer affiliated with one space or place, but rather with multiple spaces and places throughout the world. Everyday modes of dress that have originated within the West do not necessarily signify Western values, since this ignores their creative appropriation in local contexts (Cheang 2017). I use the term local to refer to dress practices that are smaller in scale, and more specific and familiar to a certain group, community, geographical region, city, or state. In contrast, the term global is used to denote the style of clothing, fashion trends, or dress practices that are worn more ubiquitously throughout the world. Throughout this book, fashion is understood as the cultural practice of dress, imbued with a sense of continuous change and the shared consensus of trends; both are intrinsically connected to our individual experiences of being in the world, and embodying multiple subjectivities, whether of race, gender, age, sexuality, ethnicity, class, and nationality.

Global Dress Cultures

As a multifaceted form of cultural expression, dress is well equipped as a medium to analyze the widespread economic and cultural exchanges that have transformed contemporary social life and resulted in the interwoven processes of fragmentation, cross-fertilization, and hybridization. The adoption of mass-produced Western-style clothing throughout the world might suggest that we are witness to a pervasive and homogenized global culture. This would equate globalization, which unequivocally takes place on uneven terms of power, with a one-directional force of cultural imperialism that has standardized, homogenized, Westernized, and Americanized more vulnerable cultures (Barber 1996; Huntington 1996; Friedman 1998). Yet this oversimplified perspective does not account for the numerous cultural and stylistic particularities that have been mobilized when Western-style dress is worn in ambiguous ways, often reconfigured for local tastes, or adopted for different reasons, possibly even as a form of resistance to the West. Arjun Appadurai (1986) has acknowledged that objects in cross-cultural networks have no intrinsic meaning but acquire new values through their exchange; in fashion, the different contexts in which Western-style clothing has been worn reveal articulations and negotiations that are variable and dialectical, based upon their new uses and requirements.

Appadurai has theorized the complex interactions and exchanges of information and ideas since the late 1980s as a series of conceptual frameworks, comprised of overlapping flows and connections between economic, political, and cultural constructs that are continually in flux. He coined the terms ideoscapes, technoscapes, mediascapes, ethnoscapes, and finanscapes to describe these multiple realities, which shift in accordance with one another and establish tensions between the warp of cultural homogeneity and the weft of cultural heterogeneity (1996: 33). It is within this hybrid space, where the weft is drawn through the warp, that new sartorial expressions are generated as two hitherto relatively distinct forms, types, patterns, or styles of dress mix and match. Certainly, all cultures have been hybrid for a long time, due to trade, slavery, warfare, travel, and migration, but the development of media and information technologies throughout the 1990s and beyond have substantially expanded the contact that different cultures have had with one another, and accelerated the speed at which these global interactions have occurred (Kraidy 2005: 21). Jan Nederveen Pieterse has eloquently described hybridization, and the heightened connectivity of contemporary global culture, as a process by which multifarious identities are “braided and interlaced, layer upon layer” (2009: 145). His use of a dress metaphor is a crucial reminder that globalization, in its economic, political, cultural, and technological dimensions, is intricately woven into everyday life; it shapes, encloses, exposes, and interacts with different bodies, defining and expressing personal and collective identities.

What Is Brazilian Dress?

The key focus of the analysis throughout this book is the impact of globalization on Brazilian dress practices. The development of Brazilian dress reveals a long history of cross-cultural contact, slavery, and immigration. It is a complex and fluid process by which Brazil, since it was first colonized by the Portuguese in 1500, has absorbed but also reinterpreted influences that stem from its indigenous populations, as well as from Europe, Africa, Asia, and the United States. Brazilian dress innovations illuminate Brazil’s role as an active participant in global fashion culture, unsurprising given that it is the fifth largest and fifth most populous country in the world. The success of Brazilian fashion designers such as Alexandre Herchcovitch (Figure 1.0) enables us to see the country as something far greater than just a source of exotic inspiration to the West. His darker designs, as Brandini (2009) has articulated, challenge recurring stereotypes in European and North American fashion magazines, which still resort to oversimplification in their representation of Brazilian culture as an exotic spectacle, failing to appreciate the internal subtleties of the country’s racial, religious, social, cultural, geographical, and sartorial diversity. From North to South, huge variables in culture and climate necessarily impact directly upon the everyday clothing choices made available to Brazilians. It leads one to question whether there is a form of dress characteristic of Brazilian culture or conspicuously national in character. Simplistic outsider reactions might suggest the bikini or Havaiana flip-flops, possibly even carnival costume, but this tells us more about foreign perceptions of Brazil—which have tended to treat Rio de Janeiro as a synecdoche for the entire country (Root and Andrade 2010)—than of the lived experience of dress for most Brazilians. Any attempt to define Brazilian dress in a sweeping brushstroke is a palpable reminder that national identity, like clothing, is a material construct, not an intangible essence—an ongoing social process of articulation and negotiation that involves both insiders and outsiders to the group. There is an incredible variation in dress styles in Brazil. The differing styles tell multiple stories about their wearers, revealing global networks of ideas and objects that are in dialogue with local identities. The forms of Brazilian dress analyzed throughout this book include, but are not limited to, indigenous forms of clothing, such as the complex sartorial system of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, who live in the state of Rondonia and combine jewelry and body paint with Western-style shorts and T-shirts, in addition to ceremonial dress, such as the white outfits worn by baianas in Salvador da Bahia, who adhere to the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé and wear a hybrid fusion of sartorial elements that originate from Europe and West Africa (Mohs Gage 2016). I analyze not only low fashion, such as the localized use of Lycra among anonymous Brazilian designers influenced by interna...