This is a test

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Translated into English for the first time, the letters collected here bring to life one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century, Ludwig Wittgenstein.

In letters written over forty years, we see how his ideas and relationships developed during his time as a prisoner of war, a school teacher, an architect and throughout his years at Cambridge. Always frank and often brutally honest, these letters between Wittgenstein, his brother Paul and his three sisters, Hermine, Margaret and Helene are filled with a familiarity and an intimacy. They allow us to enter the bygone world of an extraordinary family, revealing a side of Wittgenstein we have never seen before.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Wittgenstein's Family Letters by Brian McGuinness, Peter Winslow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Language in Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

LUDWIG’S EARLY LETTERS: THREE LETTERS FROM 1908

A nineteen-year-old Ludwig moved to Manchester in May 1908, after three semesters studying mechanical engineering at the Technical High School Charlottenburg (1906–1908). As a rather informal research student at the university, he was involved in experiments and research on aeronautics until 1911. In the autumn of 1912 Ludwig left Manchester prematurely. Still enrolled for the academic year, he moved to Cambridge to study logic and philosophy with Bertrand Russell.

In her Family Memories, Hermine speaks of ‘the dual and conflicting inner vocation’ under which he suffered. As early as 1909, as we know from Ph. E. Jourdain’s diary, Wittgenstein presented his proposals for the solution of a leading problem of mathematical logic to the Russell circle, and most likely in the summer of 1911 he got in contact with the great logician Gottlob Frege. Encouraged by Frege and Russell, he decided to become a philosopher instead of an aeronaut. He spent the two years of 1911/12 and 1912/13 in Cambridge and the academic year 1913/14 in Norway, developing the logical basis of his early philosophy.

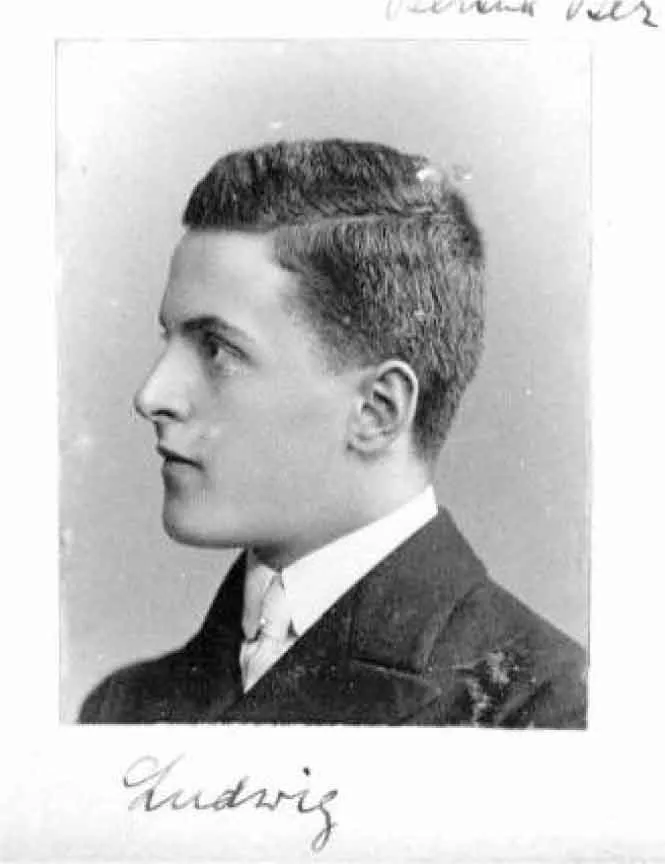

Young Ludwig © The Brenner-Archiv.

1 Ludwig to Hermine

[1908]1

Dear Mining!

I think about you very often, and your painting comes to mind every time! Each and every time I revisit my conviction that the single most useful thing you can do is to procure simple geometric objects and study them from various perspectives until it’s clear why a shadow falls precisely at such and such a place, etc., etc., and how that is connected with the position of the light source, and so on. Whenever you draw complicated objects, intentionally simplify them first and create a sketch of such and such an object so simplified; then you won’t have any difficulties in adding further details to a second sketch, etc. Here, however, it is necessary that you draw the sketch so that it’s physically complete and entirely clear to you. The object can be as simplified as you want it to be: e.g., a tree trunk drawn as a cylinder with branches emerging from it. But you shouldn’t just draw the shadows as they truly fall with respect to the tree, but, as they would fall, for instance, if the sun were illuminating the tree from a particular angle and if it were not overshadowed by other trees. By doing it this way, you’ll see what’s essential about any given shadow, etc., etc.

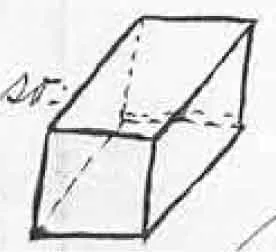

Or you’ll see that the crown of a tree is similar, say, to the form of a ball’s surface. So draw it only as if it were a completely smooth ball and shade it accordingly, then add the details only in another sketch. What is more, if an object is shiny and others are reflected in it as, say, in any polished metal object, then draw it first as if it were matt and shade it from that point of view as well; only then should you add, in another sketch, the highlights the object’ll have on account of its finish, etc. The main thing is always that, with each sketch, you draw a completely concrete object and that, consequently, you see an object in front of you whenever you look at each sketch, which you can compare with the object you intended to draw. That object may, as I’ve already said, be as simplified as it wants to be in your sketch. But it has to be an object, not something flat. Perhaps you’ll now object that you can’t, e.g., imagine how a shiny object would look if it were matt, but you will learn from your simple geometric models how certain forms of object look, and if you were to draw, say, an iridescent pyramid, then you’ll always be able to first draw how your pyramid would have looked if it were painted white and to add the less essential tones only later. But I have yet to recommend something of particular importance: in sketching objects, remember to draw the lines and edges which you can’t actually see, but which more readily permit what’s essential about the object to come to the fore: for example, draw a prism like this

and not like this

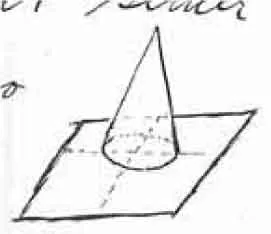

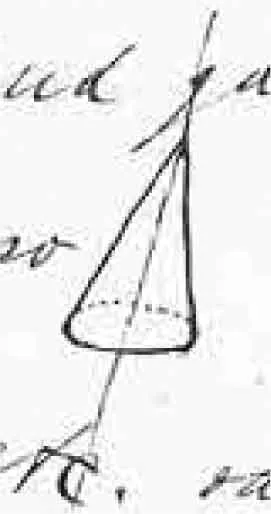

that is, with the edges which are actually hidden, so that the physical connections are completely clear to you – or a cone like this

with its axis, etc., etc., or like this

so that, e.g., the orientation of the base surface becomes clearer to you, and so on. I hope I have expressed myself clearly.

Your devoted brother,

Ludwig

2 Ludwig to Hermine

Ludwig arrived at the Glossop observatory during the summer of 1908. In a letter to Hermine of 29 May 1908 – the complete text of which seems to be lost – he reports how he and Mr Rimmer, a meteorologist and observer, were the only ones living in a secluded guesthouse. The food and toilet facilities were ‘rustic’, and Ludwig had difficulties in growing accustomed to it all. While his previous job consisted only in making observations, his current ‘job was to provide kites, which had hitherto been ordered elsewhere’. What he missed, though, was a friend, and he was keeping a lookout among the students who visited the observatory on Sundays. He was sleeping well and reports that ‘if my own ego weren’t gnawing at me, then I would really have to find it agreeable here for the time being’.

3 Ludwig to Hermine

20 October 1908

Dear Mining!

I was with Lamb2 a few days ago, and he is going to attempt to solve the equations3 which I most recently came up with and which I showed him. He said he doesn’t know for sure whether they are solvable with today’s methods, and I am therefore very curious to hear how his attempt turns out. Incidentally, he was very gracious with me, which is quite a lot for a man some 70 years of age.4 My evil spirits put me in the stupidest of moods imaginable. As I was leaving the university after my talk with Lamb, my ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- People and Places

- Wittgenstein family tree

- Introduction by Brian McGuinness

- 1 Ludwig’s Early Letters: Three Letters from 1908

- 2 The Great War: August 1914 to April 1918

- 3 Captivity: November 1918 to September 1919

- 4 The elementary school years: October 1920 to March 1926

- 5 A Viennese Intermezzo: A Letter from Late 1928?

- 6 Cambridge: January 1929 to February 1938

- 7 Second World War: March 1938 to May 1945

- 8 Ludwig’s Last Letters: January 1946 to April 1951

- Appendix

- Index

- Copyright