![]()

PART ONE

HISTORIES

Popular music lends itself particularly well to historical study: different styles of music have clear paths of development and influences can be mapped out over the years of the twentieth century. A grasp of the history of the music, its listeners and the institutions that produce it provides us with an explanation of why music is as it is today. In addition, the study is interesting in itself because it can reveal how and why music-making and consumption were different in the past from how they are now. For this reason a good historical analysis of popular music will attempt to look at the processes of development and change as well as drawing out principles of analysis that can be used for any period of music history, including our own.

Studying history involves the study of both primary and secondary material. Because the music industry and much music consumption is focussed on the recording of music performance, there is a large amount of primary material available for study through records and videos, and associated films, memorabilia and media reporting are archived and often commercially available today. The importance of the history of popular music is signalled by the large number of books (both general and academic) on the subject. Because of this abundance of secondary material the aim of these next four chapters is not to provide a definitive history of popular music, but to indicate what conclusions can be drawn from analysing existing histories, and to develop a set of tools that will enable you to analyse some moments of popular music history for yourself.

This part of the book is divided into four chapters. The first will examine the ways that authors have told the story of popular music, and the differences and commonalities of these histories. The chapter then looks at some of the criticisms of these existing histories, and offers a model for undertaking a historical analysis of popular music culture. Chapters 2 and 3 look in detail at two parts of this model, so that you can understand the approach in some detail. The fourth chapter presents case studies to show how this analysis can be applied in practice, along with a discussion of online music archives and television pop music documentaries.

![]()

1

CONSTRUCTING HISTORIES OF POPULAR MUSIC

This chapter examines how histories of popular music in books, online and in television documentaries have been constructed, along with some of the criticisms of these conventional approaches. Engaging with the histories that have already been produced will enable you to undertake analyses of your own, and encourages you to ask some important questions about the way we understand what happened in pop history. The final section of the chapter outlines a model for approaching a historical analysis of moments in popular music’s past that builds upon the most useful elements from existing accounts and the critiques of these histories. This knowledge and skill is central to the approach taken in the subsequent three chapters.

The chapter poses some fundamental questions about the pop histories that currently exist. By working through your own answers to these questions you will start to develop the understanding and skill that is necessary to do your own analysis of existing histories of pop found in books, online and in television documentaries.

- What’s the difference between a history of popular music and a study of something that happened in popular music in the past?

- Why isn’t there just one, widely agreed, history of popular music?

- What influences the way pop music histories are written and produced?

- What sorts of criticisms are made of the histories we can already read and watch?

- What should we look at when we do our own historical analysis of a moment in pop’s past?

Histories construct a narrative of the past in which the significance of certain events are emphasised over others, and ideas of cause and effect are woven into an unfolding story. In histories of popular music these narratives are usually built around musical artists, genres of music and the social worlds in which they operated, and the histories are given a strong sense of chronology through the use of key dates. These histories ‘tell the story’ of how pop changed over time, usually take a sweep of time greater than the careers of individual artists, and are usually concerned with general shifts in the music itself. We can find these histories in book form, on websites, or as television or radio broadcasts.

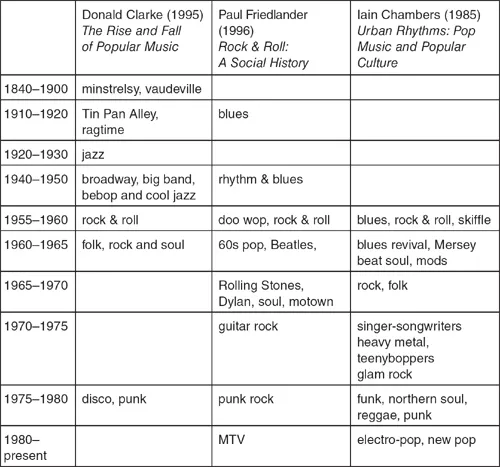

However, even though they all present a chronology of musical and social events, one of the first thing that strikes the reader flicking through books or websites on popular music history, or the viewer watching television documentaries, is that there is very little consensus about which musicians and which genres are significant. Even when these books, websites or broadcasts are presented as general histories of pop, they often cover very different periods of time. A comparison of three such books, shown in Figure 1.1, reveals this clearly.

Figure 1.1 A schematic of three histories of popular music

Comparing the three lists, it is apparent that each book constructs a very different history of popular music. This is in part because the books are focussed on different questions and make different arguments. Clarke’s history contrasts what he considers the two golden decades of popular music starting in 1940 with what he sees as the fall of popular music to the present day. Friedlander traces the origins and then dominance of rock music in the 1960s and 70s. Chambers focusses on British popular culture and music from 1956 to the early 1980s.

It is valuable to have an overall sense of what music was being made in different periods and the schematic of the contents of these three books is a good starting point. However, as this simple exercise demonstrates there is no one history of popular music, but many different ones. As well as differing in their styles of scholarship or writing, each book also differs in the particular history that it constructs. It is important that we therefore ask questions about why they highlight particular people, styles and moments, and what sorts of histories they therefore construct.

Activity 1.1 Analysing histories of popular music

Produce an analysis of other books on the history of popular music. Select three histories of popular music from your library. Using the contents page and the chapter subheadings, produce a schematic of the dates and key musicians and musics used to tell that story of popular music. What story do they tell? What periods do they emphasise? Do they see popular music as progress? Or decline? How important are non-musical events in the story? What role is assigned to the music industry?

For all their different emphases on different musicians, however, most histories of popular music share common features in the way they are constructed. First, they often outline their history as a series of dramatic disruptions. Second, they draw a clear distinction between ‘mainstream’ musical culture and a marginalised ‘alternative’ one (usually they champion new alternative music cultures). Finally, they emphasise the idea of musical roots, so that each new musical form is understood in terms of earlier precedents. Understanding these characteristics will sharpen your ability to read and research other histories critically; once you have become familiar with them you will be able to discern them in almost all broadcast documentary, online and book-length histories.

SIGNIFICANT MOMENTS IN A HISTORY OF DISRUPTION

Like the vast majority of other such histories, the histories listed in Figure 1.1 are built upon types of music and artists understood as being recognisably different from those forms that preceded them. That is, these are histories of change and disruption. New music is presented as revolutionary in some way, and it is the abrupt changes in popular music that each author wants to contextualise or celebrate. Of course there are also other narrative components – in the examples in Figure 1.1 for instance, Clarke uses a narrative of decline, while Friedlander in contrast uses a narrative of maturity – but the notion of abrupt and significant new musical forms is there centrally, as it is in almost all such histories. However, we should not see each disruption as of equal significance. When dealing with a moment of disruption you need to ask questions about the particular historical significance of that moment. For instance: in what ways did particular artists change the music? Was the music of these artists widely liked, or did it in some way articulate the ‘voice’ of a particular group or subculture? Why are these events significant: because they show a change in music-making, or in music consumption, or in the mediation of the music?

As you investigate various representations of each historical moment you will discover that there is no consistency in the selection of music or artists that populate these histories. For instance, Clarke selects two types of music for the 1920s and 30s: Tin Pan Alley and ragtime, but they are selected for very different reasons. While Tin Pan Alley is the name given to the mainstream commercialised songwriting that dominated music publishing and then radio, film soundtracks and recorded music for urban white Americans through the first half of the century, ragtime was a short-lived music with more of a minority appeal. It remains significant for Clarke because it is one of the earliest example of a musical form rooted in African-American culture that gained popularity with a white American and European audience.

We must be aware, then, of two important points. First, each historical moment was as musically and culturally eclectic and diverse as today’s popular musical culture. Second, each historical moment was not necessarily dominated by the music or artists identified with that moment by historians. A particular musical form may have significance for a particular historian not because of its role at that time, but in some future moment. For instance, the blues music of the 1940s was not particularly influential on the mainstream of American and European popular music at the time, but became hugely influential on the popular music of the 1950s and 1960s. In almost all cases the music identified with an era was not the best selling, nor the most exposed in the wider media, but is significant in some other way that the author often assumes (even if they are not always explicit).

THE MAINSTREAM AND THE MARGINALISED UNDERGROUND

Most histories emphasise musical forms which at their moment of origin had small followings, and which were often produced on the margins of the record industry. Dave Harker (1992) has pointed out that the best-selling records of the late 1960s – a period often written about as dominated by the classic period of rock – were soundtrack albums from film and theatrical musicals like The Sound of Music. In the 1960s, rock-based musical forms were named ‘the underground’ to distinguish them from the forms of music which dominated record releases and sales, radio plays and film and television appearances. Although the term ‘underground’ has moved in and out of general usage and, of course, has been used to define some very different sounds, the concept remains a very useful one to understand the history of popular music.

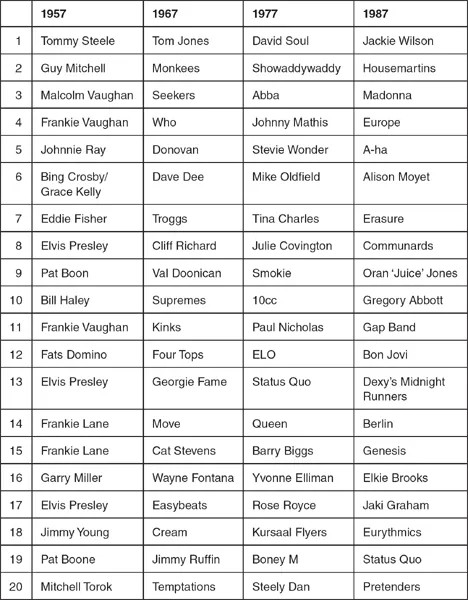

The emphasis in histories on less prominent sounds can be demonstrated quite simply by examining the sales charts for particular years highlighted in the histories. Figure 1.2, for instance, provides a comparison of the artists in the British Top 20 singles charts in the same week in 1957, 1967, 1977 and 1987.

In most histories these years are constructed as emblematic of rock and roll with Elvis Presley, psychedelic rock (and maybe soul) with the Beatles (and Otis Reading), punk (and maybe disco) with the Sex Pistols (and the Bee Gees), and house with DJ artists like Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk. My analysis of these charts suggests that even by the most generous interpretation there is never more than 25 per cent of each type of music to be found in the sample chart for that year. In fact it is mainstream pop music that is dominant in each chart, accounting for between 50 and 75 per cent of the artists in each sample chart. Interestingly, there were the same number of rock artists charting in the sample chart of 1987 as 1967, and while it is possible to identify five rock and roll singles in 1957, four rock and four soul singles in 1967, three disco singles in 1977 and five dance-based singles in 1987, the vast majority of them relied very heavily on the conventions of mainstream pop. Additionally, in January 1977 there were no punk singles at all, and in January 1987 there was no house music (although both styles are apparent in the lower Top 40 later in the those years).

Figure 1.2 Sample Top 20 singles charts for the second week in January 1957, 1967, 1977 and 1987

Source: D. Rees, B. Lazell and R. Osborne (1992) 40 Years of NME Charts. London: Boxtree.

Of course it could be countered that rock and roll, soul and house were, in 1957, 1967 and 1987 respectively, American phenomena, or that psychedelic rock was usually issued on LPs (‘long-playing’ records) rather than singles, or that punk and house were issued by small independent companies not well represented in the high street shops used to construct the charts, and so were unlikely to be prominent in a UK Top 20 singles chart. These are all telling points, but they merely reinforce the fact that however significant these were as cultural and musical phenomena, at these times at least, these forms of music were being produced and distributed on the margins of the record industry, and purchased by a minority of music consumers.

The historians of popular music culture, then, emphasise forms of popular music and artists that were not always even dominant in popular music culture of the time they are examining. Rather, they emphasise new sounds and styles of artists. The historical story is that they are part of a new type of music that starts in the margins and moves into the mainstream. Its existence in the margins is seen as significant because the music was associated with other significant social or cultural movements, or because the performers introduced radically different forms of music-making. A music’s adoption by the mainstream is presented as a decline in its social relevance or vigour. Rock and roll, rock, punk and house are all presented in this way in histories of popular music.

We cannot read these histories, then, as accounts of what was happening in popular music culture at a particular time, but as ways of highlighting certain values (those of innovation or social significance) over others, and of processes through which new musical or social ideas move from a minority interest to have a place in the mainstream. This distinction between the underground and the mainstream is itself an over-simplification, and the processes of change in popular music culture are far more complex. Nevertheless, as will become clearer in the rest of this book, the concepts of the ‘mainstream’ and the ‘margins’ does allow us to understand that there are differences between different parts of popular music culture. Different parts of the music industry and the wider media are organised around different patterns of music production and promotion. And different social groups give significant meanings to different ways of buying, listening and dancing. In the historical dimension this mainstream/margins distinction allows us to see how the sounds and meanings of music relate to these sociological patterns, and how these elements have changed over time. As such, the idea is often linked to the notion that histories explain the roots of a type of music.

MUSICAL ROOTS

The idea of change constitutes a central characteristic of histories of popular music. As I have already suggested, one of the reasons that these histories examine just one particular type of music in one time period is that they can then highlight a process of musical development. Marginal musics – particularly those established before the 1950s – are examined simply because they are seen as constituting the roots of a later style. This idea of musical roots is the final characteristic of popular music histories. The titles of many histories cannot help but belie this approach. Right On: From Blues to Soul in Black America (Haralambos, 1974), From Blues to Rock (Hatch and Millward, 1987), The Roots of the Blues (Charters, 1981) and Origins of the Popular Style (Van der Merwe, 1989) are all good examples.

Simon Frith opens his influential book on popular music, Sound Effects (1983), with such a study of ‘rock roots’. In it he examines rock music as...