- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Doing Conversation Analysis

About this book

This is the book for introducing and getting to grips with conversation analysis. Accessible, comprehensive and very applied.

- Steven Wright, Lancaster University

"A clearly written book. It puts CA into perspective by presenting exemplary studies and differentiating CA from other approaches to discourse. It is full of advice concerning the technicalities of recording, transcription and analysis. It will be most useful to my students."

- Spiros Moschonas, University of Athens

The Second Edition of Paul ten Have?s classic text Doing Conversation Analysis has been substantially revised to bring the book up-to-date with the many changes that have occurred in conversation analysis over recent years.

The book has a dual purpose: to introduce the reader to conversation analysis (CA) as a specific research approach in the human sciences, and to provide students and novice researchers with methodological and practical suggestions for actually doing CA research.

The first part of the book sets out the core theoretical concepts that underpin CA and relates these to other approaches to qualitative analysis. The second and third parts detail the specifics of CA in its production of data, recordings and transcripts, and its analytic strategies. The final part discusses ways in which CA can be ?applied? in the study of specific institutional settings and for practical or critical purposes.

- Steven Wright, Lancaster University

"A clearly written book. It puts CA into perspective by presenting exemplary studies and differentiating CA from other approaches to discourse. It is full of advice concerning the technicalities of recording, transcription and analysis. It will be most useful to my students."

- Spiros Moschonas, University of Athens

The Second Edition of Paul ten Have?s classic text Doing Conversation Analysis has been substantially revised to bring the book up-to-date with the many changes that have occurred in conversation analysis over recent years.

The book has a dual purpose: to introduce the reader to conversation analysis (CA) as a specific research approach in the human sciences, and to provide students and novice researchers with methodological and practical suggestions for actually doing CA research.

The first part of the book sets out the core theoretical concepts that underpin CA and relates these to other approaches to qualitative analysis. The second and third parts detail the specifics of CA in its production of data, recordings and transcripts, and its analytic strategies. The final part discusses ways in which CA can be ?applied? in the study of specific institutional settings and for practical or critical purposes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Considering CA

1

Introducing the CA Paradigm

Contents

What is ‘conversation analysis’?

The emergence of conservation analysis

The development of conservation analysis

Why do conservation analysis?

Contrastive properties

Requirements

Rewards

Purpose and plan of the book

Exercise

Recommended reading

Notes

Conversation analysis1 (or CA) is a rather specific analytic endeavour. This chapter provides a basic characterization of CA as an explication of the ways in which conversationalists maintain an interactional social order. I describe its emergence as a discipline of its own, confronting recordings of telephone calls with notions derived from Harold Garfinkel’s ethnomethodology and Erving Goffman’s conceptual studies of an interaction order. Later developments in CA are covered in broad terms. Finally, the general outline and purpose of the book is explained.

What is ‘conversation analysis’?

People talking together, ‘conversation’, is one of the most mundane of all topics. It has been available for study for ages, but only quite recently, in the early 1960s, has it gained the serious and sustained attention of scientific investigation. Before then, what was written on the subject was mainly normative: how one should speak, rather than how people actually speak. The general impression was that ordinary conversation is chaotic and disorderly. It was only with the advent of recording devices, and the willingness and ability to study such a mundane phenomenon in depth, that ‘the order of conversation’ – or rather, as we shall see, a multiplicity of ‘orders’ – was discovered.

‘Conversation’ can mean that people are talking with each other, just for the purpose of talking, as a form of ‘sociability’, or it can be used to indicate any activity of interactive talk, independent of its purpose. Here, for instance, are some fragments of transcribed ‘conversation’ in the sense that there are people talking together.2

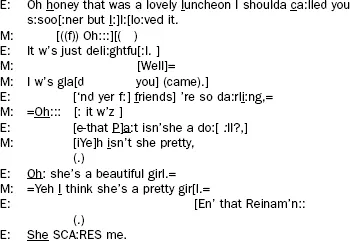

EXCERPT 1.1, FROM HERITAGE, 1984A: 236 [NB:VII:2]

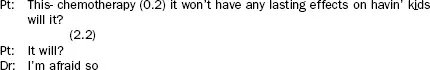

EXCERPT 1.2, FROM FRANKEL, 1984: 153 [G.L:2] [GLOSSES OMITTED]

The first excerpt (1.1), from a series of telephone conversations among friends, would generally be considered part of ‘a conversation’, while the second (1.2), from a medical consultation, would not. The social import of the two occasions is rather different, but the excerpts could be both items for serious conversation-analytic study since they are both examples of what Emanuel Schegloff (1987c: 207) has called talk-in-interaction. Conversation analysis, therefore, is involved in the study of the orders of talk-in-interaction, whatever its character or setting.

To give a bit of a flavour of what CA is all about, I will offer a few observations on the two quoted fragments. In excerpt 1.1, E apparently has called M after having visited her. She provides a series of ‘assessments’ of the occasion, and of M’s friends who were present. E’s assessments are relatively intense and produced in a sort of staccato manner. The first two, on the occasion and the friends in general, are accepted with Oh-prefaced short utterances, cut off when E continues. ‘Oh’ has been analysed by John Heritage (1984b) as a ‘news receipt’.The assessments of Pat are endorsed by M with ‘yeh’, followed by a somewhat lower level assessment: ‘a do:: ll?,’ with ‘Yeh isn’t she pretty,’, and ‘Oh: she’s a beautiful girl.’, with ‘Yeh I think she’s a pretty girl.’.These observations are in line with the tenor of findings by Anita Pomerantz (1978; 1984) on ‘compliment responses’ and ‘down-graded second assessments’. The ‘Oh-receipted’ assessments can be seen to refer to aspects of the situation for which M as a host was ‘responsible’, while it might be easier for her to ‘share’ in the assessments of the looks of her guests, although she does so in a rather muted fashion. The ‘work’ that is done with these assessments and receipts can be glossed as ‘showing and receiving gratitude and appreciation, gracefully’.

In the second fragment, excerpt 1.2, the context and the contents of the assessments are markedly different. The patient proposes an optimistic assessment as to the effect of her forthcoming chemotherapy, after which the physician is silent, leading to a remarkably long, 2.2-second pause. In so doing, he can be seen as demonstrating that he is not able to endorse this positive assessment. Thereupon, the patient ‘reverses’ her statement in a questioning manner, ‘It will?’, which the doctor then does confirm with: ‘I’m afraid so’.We can say that the conversational regularity which Harvey Sacks (1987) has called ‘the preference for agreement’ has been used here by the physician to communicate that the situation is contrary to the patient’s hopes, while she uses it to infer the meaning of his ‘silence’ (cf. Frankel’s 1984 analysis of this case). In both cases, aspects of the ‘pacing’ of the utterances, as well as the choice of ‘grades’ or ‘directions’, contribute to the actions achieved. It is such aspects of ‘the technology of conversation’ (Sacks, 1984b: 413; 1992b: 339) that are of interest here.

The emergence of conversation analysis

The expression ‘conversation analysis’ can be used in wider and more restricted senses. As a broad term, it can denote any study of people talking together, ‘oral communication’, or ‘language use’. But in a restricted sense, it points to one particular tradition of analytic work that was started by the late Harvey Sacks and his collaborators, including Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson. It is only in this restricted sense that ‘conversation analysis’ or ‘CA’ is used in this book.

In this restricted sense, CA was developed in the early 1960s in California.3 Harvey Sacks and Emanuel Schegloff were graduate students in the Sociology Department of the University of California at Berkeley, where Erving Goffman was teaching. Goffman had developed a rather distinctive personal style of sociological analysis, based on observations of people in interaction, but ultimately oriented to the construction of a system of conceptual distinctions. Simplifying complex historical influences, one could say that Goffman’s example opened up an interesting area of research for his students, the area of direct, face-to-face interaction, what he later has called ‘The interaction order’ (1983). Sacks and Schegloff, however, were never mere followers of Goffman.4 They were open to a lot of other influences and read widely in many directions of social science, including linguistics, anthropology, and psychiatry.

It was Harold Garfinkel, however, who was to be the major force in CA’s emergence as a specific style of social analysis. He was developing a ‘research policy’ which he called ‘ethnomethodology’ and which was focused on the study of common-sense reasoning and practical theorizing in everyday activities. His was a sociology in which the problem of social order was reconceived as a practical problem of social action, as a members’ activity, as methodic and therefore analysable. Rather than structures, functions, or distributions, reduced to conceptual schemes or numerical tables, Garfinkel was interested in the procedural study of common-sense activities.

This apparently resonated well with Sacks’ various interests, including his early interest in the practical reasoning in case law, and later in other kinds of practical professional reasoning such as police work and psychiatry. These things came together when Sacks became a Fellow at the Center for the Scientific Study of Suicide in Los Angeles in 1963–4. There he came across a collection of tape recordings of telephone calls to the Suicide Prevention Center. It was in a direct confrontation with these materials that he developed the approach that was later to become known as conversation analysis.

Two themes emerged quite early: categorization and sequential organization. The first followed from Sacks’ previous interests in practical reasoning and was not essentially bound up with these materials as interactional. The second, however, was in essence ‘new’ and specific to talk-in-interaction as such. It can be summarized briefly as the idea that what a doing, such as an utterance, means practically, the action it actually performs, depends on its sequential position. This was the ‘discovery’ that led to conversation analysis per se.5

From its beginnings, then, the ethos of CA consisted of an unconventional but intense, and at the same time respectful, intellectual interest in the details of the actual practices of people in interaction. The then still recent availability of the technology of audio recording, which Sacks started to use, made it possible to go beyond the existing practices of ‘gathering data’, such as coding and field observation, which were all much more manipulative and researcher dominated than the simple, mechanical recording of ‘natural’, that is non-experimental, action.

Audio recordings, while faithfully recording what the machine’s technology allows to be recorded, are not immediately available, in a sense. The details that the machine records have to be remarked by the listening analyst and later made available to the analyst’s audience. It is the activity of transcribing the tapes that provides for this, that captures the data, so to speak. In the beginning, transcripts were quite simple renderings of the words spoken. But later, efforts were made to capture more and more details of the ways in which these words were produced as formatted utterances in relation to the utterances of other speakers. It was the unique contribution of Gail Jefferson, at first in her capacity as Sacks’ ‘data recovery technician’ (Jefferson, 1972: 294), and later as one of the most important contributors to CA in her own right, to develop a system of transcription that fitted CA’s general purpose of sequential analysis. It has been used by CA researchers ever since, although rarely with the subtlety that she is able to provide.6

It was the fitting together of a specific intellectual matrix of interests with an available technology of data rendering that made CA possible. And once it became established as a possibility, which took another decade, it could be taken up by researchers beyond its original circle of originators and their collaborators. There are many aspects of its characteristics and circumstances that have contributed to CA’s diffusion around the world (of which the present book is one manifestation), but the originality of its basic interests, the clarity of its fundamental findings, and the generality of its technology have certainly contributed immensely.

The development of conversation analysis

For a characterization of CA’s development, one can very well use the ideas that Thomas Kuhn developed in his The structure of scientific revolutions (1962).As Schegloff makes clear in the ‘Introduction’ to Sacks’ edited Lectures on conversation (1992a; 1992b), Sacks and he were on the look-out for new possibilities for doing sociology which might provide alternatives to the established forms of sociological discourse, or ‘paradigms’ in Kuhn’s parlance. And what they did in effect was to establish a new ‘paradigm’ of their own, a distinctive way of doing sociology with its particular interests and ways of collecting and treating evidence. As a ‘paradigm’, CA was already established when Harvey Sacks died tragically in 1975. The work that remained to be done was a work of extension, application, and filling in gaps, what Kuhn has called ‘normal science’. What was already accomplished was the establishment of a framework for studying talk-in-interaction, basic concepts, and exemplary studies. What still could be done was to solve puzzles within the established framework. I will now discuss some of these later developments.

From its early beginnings in Sacks’ considerations of tapes of suicide calls, CA has developed into a full-blown style of research of its own, which can handle all kinds of talk-in-interaction. When you scan Sacks’ Lectures on conversation (1992a; 1992b), you will see that most of the materials he discusses stem from two collections, the already mentioned suicide calls and a series of tape-recorded group therapy sessions. Quite often, the fact that these recordings were made in very specific ‘institutional’ settings is ignored, or at least it is not in focus. Similarly, Schegloff’s dissertation (partly published in Schegloff, 1968, and 2004), although based on calls to a disaster centre, mostly deals with general issues of conversational interaction as such, rather than with institutional specifics.

Gradually, however, Sacks, Schegloff, and their collaborators turned to the analysis of conversations that were not institutionally based.7 The general idea seems to have been that such non-institutional data provided better examples of the purely local functioning of conversational devices and interactional formats such as ‘turn-taking’ or ‘opening up closings’. From the late 1970s onwards, however, later followers of the CA research style turned their attention ‘again’ to institution-based materials such as meetings, courtroom proceedings, and various kinds of interviews. Their general purpose was to ‘apply’ the acquired knowledge of conversa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Fm

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Part 1 Considering CA

- Part 2 Producing Data

- Part 3 Analysing Data

- Part 4 Applied CA

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Transcription Conventions

- Appendix B: Glossary

- Appendix C: Tips for Presentations and Publications

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Doing Conversation Analysis by Paul ten Have in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.