![]()

1

The development of communication and language

The story of language development is a saga which has its share of unsolved mysteries and discoveries and, like all good stories, it helps us to understand more about being human. ‘A miracle’ or ‘a mystery’ are words often used about the development of communication and language, mainly because linguists cannot account in full for the speed and the apparent ease with which almost all babies acquire the essential structure of one or more languages in their first three years. In a previous account of early language acquisition (Whitehead, 2004) I referred to ‘The Big Questions’ in order to draw attention to the important questions that this special kind of linguistic study, called psycholinguistics, asks.

Two big questions occur again and again: how do we learn to understand and use our first languages, and what are the links between communication, language and thinking? This last question often surprises those people who just want to know how we all learn to speak and use words, although a moment’s thought will show that words and conversations are all about communication and sharing meanings. So, the study of early language development involves both language study, or linguistics, and the study of mental processes and learning, or psychology. These two aspects of human behaviour – language and thinking – account for much of what makes us both unique individuals and sociable persons firmly tied to our families and cultural groups. Indeed, I would argue that in learning more about language development we are finding out about human nature. You will have to judge whether I have exaggerated here, but this book will try to explain how we become communicators, talkers, thinkers and mark-makers.

The push-pull language game

For centuries people have been fascinated by the mysteries of language and some bizarre ideas inspired the earliest alleged linguistic experiments. Caring for a group of babies in strict silence and hoping that their first words would be in Latin is one legendary example. Cutting out and eating the tongues of defeated Roman soldiers in the hope of acquiring Latin is another! Legend has it that the babies died and no results from the tongues experiment are available to researchers (Mills and Mills, 1993, p. 6). More recent research and speculation is less colourful and a lot kinder, but it is just as fascinated by the commonplace yet stunning nature of acquiring language. Furthermore, modern scientific approaches are still trying to sort out ‘the babies’ and ‘the tongues’ theories about the development of early language. Does language burst out fully formed from infants, or do they have to learn it all from the speech communities they are born into?

Modern approaches are increasingly likely to point out the truth in both these extremes and suggest what I would describe as a push-pull theory. The infant is pushed into language by her own powerful inner drive to communicate and share meanings, while, simultaneously, close relationships with her carers who use specific languages pull her into a shared world of language. While it is clear that language will not develop if adults never speak to babies, it is also clear that babies have their own remarkable communication skills and some innate ability to process the language around them.

The broad patterns in this complicated process will be outlined in the following sections, but early years carers and educators should be proud that the research is based on traditions of careful child-watching and listening to children. Linguists, families and other professionals have used notes, sketches, diaries and modern audio, video and digital technologies to build up records of infants’ eye-gaze, expressions, smiles, mouth noises, recognisable and repeated sounds, gestures, first words and early conversations.

Communicating without words

Spoken recognisable words are not at the start of language and communication. A child’s first word has behind it a personal history of listening, observing and experimenting with sounds and highly selective imitations of people. Similarly, the art of conversation is rooted, well before talk, in the innate sociability and sensitivity of infants. It has been known for many years that newborn babies are most attentive to human voices, faces and eyes. They will spend surprisingly lengthy periods of time just gazing into the eyes of their carers (Schaffer, 1977; Stern, 1977). Adults on the receiving end of this adoration invariably respond by gazing back, smiling, nodding and talking to the baby ‘as if’ they were conversing with an understanding partner. They frequently stroke the baby’s face, chin and lips, perhaps to emphasise the physical sources of human speech.

Even at a few weeks old the infant’s love affair with people is shown by different reactions to persons, as opposed to interesting objects. Moving objects may be watched and reached for, but people, especially a carer, are responded to with smiles, lip movements and arm-waving (Trevarthen, 1975, cited in Harris, 1992). Getting into relationships with people probably begins in the earliest hours of life: many newborns will imitate adult face and hand movements (Trevarthen, 1993). The list of actions imitated is interesting: for example, mouth-opening, tongue-poking, eye-blinking, eyebrow movements, sad and angry expressions, and hand opening and closing. Bearing in mind that all these actions are used in normal speech production and conversations, it is clear that this early non-verbal kind of communication is the foundation for communicating with words all through our lives.

There is widespread agreement among researchers that by five or six weeks babies and their carers are regularly involved in mutually satisfying conversational activities. Infants frequently take the lead and set the pace and carers respond, even to the extent of imitating their babies. So what is significant about this for early language learning? It would appear to be something to do with the complex business of getting two minds in contact (Trevarthen, 1993; 2002), because the exchange of meanings and language are at the centre of human communication. Although the first things shared may only be eye-contacts, smiles and sounds, these quickly lead on to other possibilities. Infants and carers start to follow each other’s line of gaze, or attentional focus, and then it is but a short step to pointing, special noises, and word-like sounds. Traditional games with babies like peek-a-boo, dropping and recovering objects or giving and taking food and toys, have their own special words which are repeated again and again in highly predictable ways. Just saying or making noises, gestures and facial expressions to indicate ‘please’, ‘thank you’, ‘boo’ and ‘bye bye’ are the ordinary and unremarkable basis for getting in touch with another mind. It is done by the playful use of actions, noises and objects which stand for ideas and feelings, and it works because very young babies are not only highly sociable (Murray and Andrews, 2000), but inclined to be playful and will, given the slightest encouragement, tease their carers and muck about (Reddy, 1991).

First words

What is a word? This is a question which students of early language development, including many parents and carers, often ask. The answer will have to start with sounds, for sound is the very stuff of language, but any old sound produced at random will not be a word. Most linguists would expect a word to have the following additional characteristics:

- it is produced and used spontaneously by the child;

- it is identified by the caregiver who is the authority on what the child says (Nelson, 1973);

- it occurs more than once in the same context or activity (Harris, 1992).

The sound-making, or phonological, skills of infants are immature and go through many changes, so word identification is not easy and it is important to have this rather elaborate way of clarifying what counts as a word. The emphasis on spontaneity is there to exclude simple imitations, because a word should signal the child’s first attempts to identify and communicate meanings. We can only be certain this is happening if the child’s use of the new word is fairly consistent, or appropriate to the context in which it is uttered. This is where the agreement of the regular caregiver is so important; only the child’s partner in the games and non-verbal conversations described above knows enough about the contexts in which first words occur.

Many studies of first words are undertaken by the parents of young infants (Engel and Whitehead, 1993) and the intimate insights of professional-linguist parents have shown how some words begin to emerge as early as nine months (Halliday, 1975). At this stage the words are sounds that are personal to the infant, used consistently for requesting and indicating interest, and quite recognisable. We might want to think of these as embryo-words, noticed mainly by professional linguists, but there is no mistaking the breakthrough into ‘real’ words when it occurs. Many parents and carers can recall years later the first words spoken by their children, but it is important to bear in mind that the onset and the rate of acquisition of early words is highly variable and personal. Most babies do begin to say their first words somewhere between 12 and 18 months, but there can be earlier starts, as well as much later ones. The real value of records of children’s first words is not in the totals, but the windows they provide into children’s minds and their views of their families and the world.

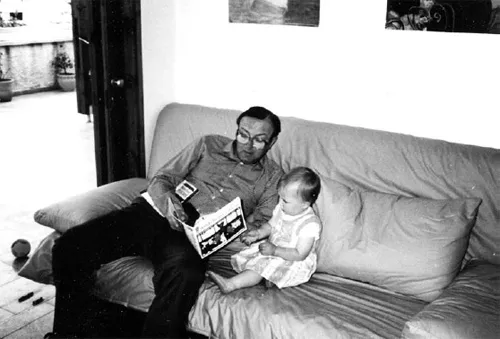

My granddaughter Natalie’s first word was ‘book’, produced at ten months and sounding much like ‘boo’. An outsider would have been ignorant of the richness of experience behind that single syllable word. In fact, like many of the first words of young infants, it stood for a whole sentence. It was a ‘come-and-read-to-me-now’ ritual which involved clambering on the couch with a pile of picture books; snuggling up to the chosen adult; then sharing in pointing at and naming pictures, and listening to rhymes and stories (Figure 1). All this wealth of experience, organisation and meaning was carried by one word, hence the great importance of a carer’s knowledge about the context of first words. Carers can also alert us to the fact that first words develop and change, because Natalie was soon using ‘book’ to include all the magazines and newspapers that came into the house.

First words can only be fully understood within the contexts in which they are uttered, but they do indicate how the young child is noticing and sorting out the world. Collections of first words are usually about such things as family members, daily routines, food, vehicles, toys and pets. These groupings are known to linguists as semantic fields because they reveal the sets of meanings around which a child’s first interests and language development are clustering. And it is not surprising that people, food, animals and possessions are highly interesting to babies and need labels early on! These semantic sets also include those important words which get people to do things for you, such as ‘up’, ‘walk’, ‘out’ and ‘gone’. The field of meaning here is part of the lifetime study of human relationships and people management. Two other very important words are acquired in these early days – ‘no’ and ‘yes’ – and usually in that order. At this point the young talker has joined the language club (Smith, 1988) and is well on the way to learning about self-assertion, as well as cooperation.

Figure 1 ‘Book’ meant ‘come-and-read-to-me-now’

More words

Single words can pack a linguistic punch, but they do have their limitations. They depend a lot on context and on the interpretive sensitivity of a carer. However, their power and flexibility increases greatly when they are combined together in order to say more complicated things. Infants vary greatly in the rate, the frequency and the complexity of their early word combinations. My eldest grandson, Daniel, was a very creative word combiner, starting with ‘door uppy’ (open the door) at 20 months and progressing to little stories by 22 months, such as ‘sea Daddy park it car’ (Daddy is parking the car by the sea). The striking thing about these utterances is that they are unique to the child, their originality is a reminder that they could not have been copied from carers or the language community. They use quite different word order: in the first example the important object of attention, the door, is named before the desired action is indicated. A similar reversal happens in the much longer example and again suggests that the focus of the child’s attention is named before the rest of the action is described. This is a very useful strategy for gaining a listener’s attention. In the latter incident the small boy was very impressed when the car was driven right on to the beach. It was literally parked by the sea!

These examples help us to see that the beginning speaker is creative, determined and resourceful as he or she struggles to use a limited hold on speech in order to communicate important new meanings. Daniel’s temporary limitations were partly physical in terms of making a range of sounds in his mouth and throat and controlling airflow and muscles; his limitations were partly linguistic in terms of the range of vocabulary and conventional grammatical structures he knew; and at not quite two years old he had a limited range of life experiences. Similar social and linguistic triumphs were also achieved by our second grandson, Dylan, again at just 22 months. A rather aggressive door-to-door fish salesman had called and been told several times by Dylan’s grandfather that he did not wish to buy his fresh fish and the door was finally slammed shut, emphasising the annoyance felt! During this incident Dylan had watched from behind his grandfather’s legs, but once the door was closed he stamped noisily down the hall shouting angrily, ‘No buy fish’. Not only was this a remarkably creative new three-word utterance, it also captured the emotional tone of the annoyance felt by the adult. Dylan had managed to reorganise his limited word collection in order to talk about an unusual encounter with fish and explore the discovery that a normally gentle, loving carer could get very angry.

Professional linguists get very excited about what young children are doing when they first start to combine words together and the reason for all the excitement is grammar. Many small children are able, in their second year, to combine words together in original ways that convey meanings to others. This is a standard definition of a grammar (see the next section). Furthermore, they have not been taught the system they have hit upon for doing this and it certainly differs from the conventions of adult language use, but it is systematic, it has a pattern and it works. It communicates meanings to users of the conventional language system. In other words, it is an early emerging grammar. Linguists describe grammars in terms of the things that they enable us to do with language, so what can these little children do with their early language system?

My 16-month-old granddaughter rushes into the bathroom shouting ‘dirty hand wash it’, and her mother is left in no doubt that she wants help to remove garden soil from her hand. Natalie’s newly emerging grammar helps her to use language in order to gain the interest and cooperation of other people – it gets things done. Her brother, Daniel, was heard to say at 20 months, as the family cat left by the kitchen window, ‘no more miaow’, a lovely comment on the absence of the cat and a skilful recycling of comments like ‘no more apple’. Grammatical word combinations of this sort gave him a way of commenting on the world and any particular state of affairs.

So, the emerging language system enables very young children to do two important things: to get things done, including involving other people, and to comment on the world. Similar conclusions about children’s earliest meaningful language have been reached by linguists and researchers (Halliday, 1975) and it is interesting to think about how important these two functions of language remain for us all through our lives.

Is this grammar?

If we do not have some understanding of what a grammar is, we are likely to go along with the majority of people who would dismiss the examples above as ungrammatical. Yet I have already claimed that linguists see early word combinations as an important development: the first evidence of grammatical speech. Why then is there considerable disagreement about the nature of grammar? The answer to this and to most other linguistic disputes, of which there are many, is that the modern study of language is constantly battling against deeply held beliefs and prejudices. Some of these ancient language myths (Bauer and Trudgill, 1998) are worth a closer look.

Prescriptive grammar

On the one side we have those beliefs about language that emphasise correctness and rules; rules which tell us how we ought to speak and write. This is known as prescriptive grammar: it prescribes what we ought to do. These rules hark back to a supposedly ‘logical’ and ‘more grammatical’ language, in fact to Latin, and are attempts to squeeze ‘vulgar’ and ‘illogical’ languages, like English, int...