![]()

1

The International and Global Dimensions of Social Policy

This chapter

- Provides a number of ways of thinking about social policy

- Provides a number of ways of thinking about globalisation

- Reviews five ways in which globalisation influences social policy

- Reviews the ways of thinking about social policy in the light of globalisation’s impact

- Offers an explanatory framework for national and global social policy change in the context of globalisation.

This book is about social policy and globalisation and the ways in which the contemporary processes of globalisation impact upon social policy. Social policy is here understood as both a scholarly activity and the actual practice of governments and other agencies that affect the social welfare of populations. An important argument of this book is that neither the scholarly activity of social policy analysis nor the actual practice of social policy-making can avoid taking account of the current globalisation of economic, social and political life. This is true in two quite distinct senses. In terms of the social policies of individual countries, global processes impact upon the content of country policies. Equally important, the globalisation of economic social and political life brings into existence something that is recognisable as supranational social policy either at the regional level or at the global level. Social policy within one country can no longer be understood or made without reference to the global context within which the country finds itself. Many social problems that social policies are called upon to address have global dimensions, such that they now require supranational policy responses. One of the arguments of the book is that since about 1980 we have witnessed the globalisation of social policy and the socialisation of global politics. By the last phrase is meant the idea that agendas of the G8 are increasingly filled with global poverty or health issues.

Social policy

Social policy as a field of study and analysis is often regarded as the poor relation of other social sciences such as economics, sociology and political science. It is dismissed as a practical subject concerned only with questions of social security benefits or the administration of health care systems. Some of those who profess the subject would insist to the contrary, that by combining the insights of economics, sociology and political science and other social sciences to address the question of how the social wellbeing of the world’s people’s is being met, it occupies a superior position in terms of the usefulness of its analytical frameworks and its normative concerns with issues of social justice and human needs.

Social policy as sector policy

The subject area or field of study of social policy may be defined in a number of ways that compliment each other. At one level it is about policies and practices to do with health services, social security or social protection, education and shelter or housing. While the field of study defined in this sectoral policy way was developed in the context of more advanced welfare states, it is increasingly being applied to developing countries (Hall and Midgley, 2004; Mkandawire, 2005). When applied in such contexts, the focus needs to be modified to bring utilities (water and electricity) into the frame and to embrace the wide range of informal ways in which less developed societies ensure the wellbeing of their populations (Gough and Woods, 2004). It is one of the arguments of this book that whereas social policy used to be regarded as the study of developed welfare states and development studies as the study of emerging welfare states, this separation did damage to both the understanding within development studies of how welfare states developed and to the actual social policies in the context of development that have too often had merely a pro-poor focus, to the detriment of issues of equity and universalism.

Social policy as redistribution, regulation and rights

Another approach to defining the subject area is to say that social policy within one country may be understood as those mechanisms, policies and procedures used by governments, working with other actors, to alter the distributive and social outcomes of economic activity. Redistribution mechanisms alter, usually in a way that makes more equal the distributive outcomes of economic activity. Regulatory activity frames and limits the activities of business and other private actors, normally so that they take more account of the social consequences of their activities. The articulation and legislation of rights leads to some more or less effective mechanisms to ensure that citizens might access their rights. Social policy within one country is made up, then, of social redistribution, social regulation and the promulgation of social rights. Social policy within the world’s most advanced regional co-operation (the EU) also consists of supranational mechanisms of redistribution across borders, regulation across borders and a statement of rights that operates across borders.

Social policy as social issues

Yet another approach to defining the subject area of social policy is to list the kinds of issues social policy analysts address when examining a country’s welfare arrangements. In other words, social policy as a subject area is what social policy scholars do. A standard social policy text (Alcock et al., 2003) lists among the concepts of concern to social policy analysts: ‘social needs and social problems’, ‘equality rights and social justice’, ‘efficiency, equity and choice’, ‘altruism, reciprocity and obligation’ and ‘division, difference and exclusion’. These are elaborated below.

- Social justice: What is meant by this concept, and how have or might governments and other actors secure it for their populations? Possible trade-offs between economic efficiency and equity appear here. Mechanisms of rationing or targeting are included.

- Social citizenship: Whereas other social sciences are concerned with civil and political aspects of citizenship, social policy analysts focus upon the social rights of citizens. What social rights might members of a territorial space reasonably expect their governments to ensure access to?

- Universality and diversity: How might social justice and access to social citizenship rights be secured for all in ways that also respect diversity and difference? Issues of multicultural forms of service provision arise, as do policies to combat discrimination and ensure equality of opportunity and agency.

- Autonomy and guarantees: To what extent do social polices facilitate the autonomous articulation of social needs by individuals and groups and enable them to exercise choice and influence over provision? How can such an approach be reconciled with guaranteed provision from above?

- Agency of provision: Should the state, market, organisations of civil society, the family and kin provide for the welfare needs of the population, and in what proportion?

- Who cares: Should the activity of caring be a private matter (more often than not done by women for men, children and dependants) or a public matter within which the state plays a role and the issue of the gender division of care becomes a public policy issue? More broadly, social policy analysts are concerned with issues of altruism and obligation. For whom is one responsible?

Social policy as a welfare regime theory

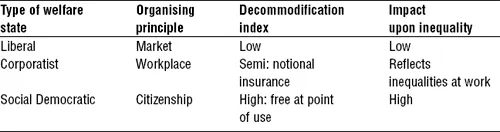

Social policy analysts have, within the context of these approaches to the subject, developed two strands of literature that might usefully be briefly reviewed. One concerns the mapping and evaluation of the diverse ways in which countries do provide for the welfare of their citizens and residents, and the other offers explanations of social policy development and welfare state difference. Most attempts to classify (OECD) welfare states into typologies start with Esping-Andersen’s (1990) classic three-fold typology of liberal, corporatist and social democratic regimes. These are distinguished in terms of their organising principles, the funding basis of provision, and the impacts of their policies on inequalities. Liberal welfare states such as the USA emphasise means-tested allocations to the poor and a greater role for the market. Corporatist welfare states such as Germany and France are based much more on the Bismarckian work-based insurance model with benefits reflecting earned entitlements through length of service. In contrast, social democratic welfare states such as Sweden place the emphasis on state provision for citizens financed out of universal taxation. The differences may be captured as in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Welfare regimes in the developed world

Note: See text about productivist welfare states of East Asia

To this must be added the fouth world of ‘productivist’ welfare described by Holliday (2000). He and others (Goodman et al., 1998; Ramesh and Asher, 2000: Rieger and Leibfried, 2003) argued that low welfare expenditure states in East Asia ensured the meeting of welfare needs through a process of state-lead economic planning and highly regulated private provision such as compulsory savings. Here social rights to be met by the state were not a central part of the social policy discourse, rather a concern to encourage family and firm responsibility.

Other analysts have drawn attention to the degree of woman-friendliness of welfare states and asked if the diverse regimes meet differently the welfare needs of carers. One typology (Siarrof, 1994 in Sainsbury, 1994) distinguishes between:

- Protestant social democratic welfare states (Sweden) within which the state substitutes for private care and women find employment in the public service so created.

- Christian democratic welfare states (France) that support women in their caring functions at home but do not make it so easy for women to enter the work force on equal terms with men.

- Protestant liberal welfare states (the USA) which offer limited support for caring work and some help towards equitable access to employment, but much of this depends on private provision of services in the marketplace.

- Late female mobilisation welfare states (Greece, Japan) where the issues of access to work and/or support for caring functions have only just entered the policy agenda.

These diverse welfare regimes have also been commented on in terms of their ethnic minority friendliness. Particular attention is focused here on the insider–outsider aspect of the ethnic citizenship basis of the German and Japanese welfare system, compared with the formal equal opportunities policies and multi-lingual education opportunities provided for in some Scandinavian countries. (For an overview of this comparative social policy literature, see Kennet, 2001, Ch. 3.)

Goodin et al. (1999) have provided the definitive evaluation of the three worlds of welfare in a longitudinal study of three exemplar countries: The Netherlands (social democratic), Germany (corporatist) and the USA (liberal). They examined empirically over time the performance of the three countries on several criteria including the level of poverty, the degree of social exclusion, the efficiency of the economy, and the capacity it offered citizens to make life choices. These authors concluded that on all criteria social democracy was superior to corporatism, which in turn was superior to liberalism. It is this empirical conclusion combined with people’s perception of the success of such regimes that has led to such a heated controversy about the perceived threats to social democracy of the global neo-liberal project.

Social policy and explanations of welfare state development

Early work in social policy to account for welfare state development was not readily able to explain diversity. Neither the ‘moralistic’ or ‘social conscience’ approach of Titmuss (1974), nor the ‘materialist’ or ‘logic of industrialisation’ approach of Rimlinger (1971) and Wilensky and Lebeaux (1958) were suited to this task. Accounts that have offered plausible explanations of diversity among welfare states include the ‘pluralist’ or ‘politics matters’ approach of Heidenheimer et al. (1991), the ‘Marxist’ or ‘class struggle’ approach of Gough (1979) and the ‘power resource’ (or ‘democratic class struggle’) approach of Korpi (1983). From these last two approaches we have learned that social democratic welfare states are associated with a high degree of working-class mobilisation and political representation, and that liberal welfare states are associated with an absence of these factors. The fashioning of cross-class coalitions and solidarities were also an important part of the universal welfare state story. The middle class were brought into (or bought off by) the Scandinavian welfare state settlement by ensuring high-quality universal services that met their needs too. In a rather different way, the conservative regimes of Germany and France met the needs of a middle class through wage-related benefits that to some extent privileged them. These types of explanation were then developed further by Williams (1989, 2001, 2005) to account not only for the class-related dimensions of welfare states but also for the gendered and ethnic-friendly character of welfare states. With the concept of ‘discourses of work, family, nation’, she argued that particular welfare state settlements were an outcome not only of class but also of gender and ethnic conflicts, degrees of mobilisation around each of these, and the associated discourses around work (who should get it and how should it be rewarded?), family (who cares for whom and with what support?) and nation (who is an insider and who an outsider regarding welfare entitlements?) deployed in these conflicts.

The chapter now turns to a consideration of the globalisation process. Having done that, we shall be able to return to these several ways in which we described the subject area of social policy and ask:

- How does globalisation affect social policy understood as sector provision of services like health and social protection?

- How does globalisation alter the way social policy analysts address issues of redistribution, regulation and rights?

- How do the issues of social justice, citizenship rights, universality and diversity, agency of provision and caring responsibilities alter within a global context?

- Does globalisation encourage developed welfare states and developing countries to adopt and prefer one or other of the diverse welfare state models that we reviewed?

- How might globalisation modify the explanations we offer for social policy development and what does it do to class, gender and ethnic welfare struggles?

Globalisation

Here are two definitions of globalisation: ‘Globalisation may be thought of initially as the widening, deepening and speeding up of world-wide interconnectedness in all aspects of contemporary life’ (Held et al., 1999); and ‘globalization [involves] tendencies to a world-wide reach, impact, or connectedness of social phenomena or to a world-encompassing awareness among social actors’ (Therborn, 2000).

When social scientists talk about globalisation they are talking about a process within which there is a shrinking of time and space. Social phenomena in one part of the world are more closely connected to social phenomena in other parts of the world. This kind of definition that sees cross-border connections as the key to understanding globalisation has to be distinguished from debates for or against globalisation. Usually these debates and conflicts are about particular international polices and practices – typically economic ones which may be associated with the wider process of globalisation but are not a necessary feature of it. These disputes are usually about the form that globalisation is taking or the politics of globalisation, rather than the fact of time and space shrinkage. Indeed, this book engages in a debate about the neo-liberal form that globalisation is taking and the kinds of global and national social policies being argued for by global actors, but it does not dispute that there is a shrinking of time and space and that globalisation is in that sense uncontestable and irreversible.

Most commentators agree that globalisation embraces a number of dimensions including the economic, political, productive, social and cultural. Among the aspects of globalisation which reflect this range of dimensions are:

- increased flows of foreign capital based on currency trading;

- significantly increased foreign direct investment in parts of the world;

- increased world trade with associated policies to reduce barriers to trade;

- increased share of production associated with transnational corporations;

- interconnectedness of production globally due to changes in technology;

- increased movement of people for labour purposes, both legal and illegal;

- the global reach of forms of communication, including television and the Internet; and

- the globalisation or ‘MacDonaldisation’ of cultural life.

These processes and other associated phenomena have in turn led to the emergence of a global civil society sharing a ...