![]()

PART ONE

The media/violence debates

The effects of violence in the media Chapter outline

This chapter provides an overview and critique of popular and academic debates about the effects of violence in the media. The title is deliberately ambiguous, pointing to ‘the media’ both as the source of stories about effects (the effects of violence in the media) and as the effective agent (the effects of violence in the media). The organisation of this chapter mirrors this dual emphasis by, first, examining the ways in which the media (and, in particular, the print media) construct the ‘media effects’ story and, second, considering what academic research can tell us about the effects of violence in the media:

• Explaining crime or Excusing male violence? | moral panics, media effects as gendered discourse, agency and accountability |

• Academic approaches to media effects | causality and influence, laboratory studies, behavioural effects |

• Cultivation and content | television violence, cultivation theory, content analysis. |

Explaining crime or excusing male violence?

It has become common practice when faced with apparently inexplicable acts of violence that commentators turn to the question of possible media influence. The judge at the trial of the ten-year-old murderers of James Bulger did it, suggesting that ‘exposure to violent videos’ might provide a partial explanation for their crime. In the aftermath of the Columbine High School massacre, many reporters did it, suggesting that the killers took their inspiration from the music of Marilyn Manson or The Matrix (Wachowski Brothers, 1999) or The Basketball Diaries (Kalvert, 1995). However, when we examine the nature of the evidence linking crime and media in these cases, the argument begins to unravel. Which begs the question, what is at stake in blaming the media? In exploring this question, I want to begin by examining these two notorious cases in a bit more detail.

In February 1993, in Liverpool, England, two-year-old James Bulger was kidnapped and murdered by two ten-year-old boys – Robert Thompson and Jon Venables. In his summing up at the boys’ trial in November 1993, Justice Morland suggested that ‘exposure to violent videos’ could provide a partial explanation for their crime. Video violence had not been discussed at all during the trial. In fact, it was a blurred security video and not a commercial ‘video nasty’ that had been central to the case – the apparently innocuous image of James Bulger being led out of a shopping centre by his two killers.

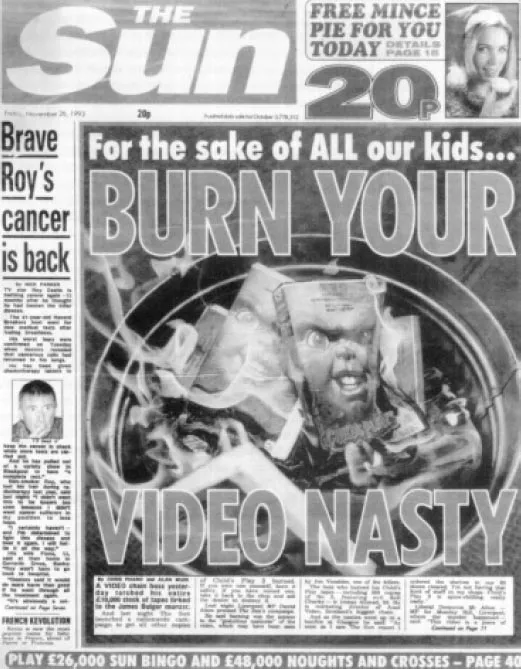

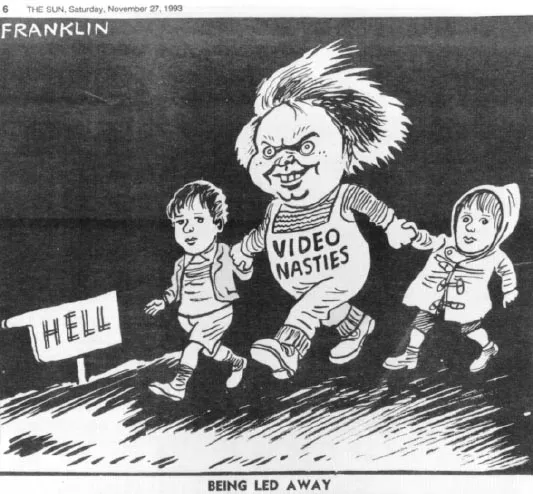

Unsurprisingly, the British press seized on the judge’s comments and one film in particular – Child’s Play 3 (Bender, 1991) – came to dominate the public debate. The day after the verdict, a front-page editorial in The Sun urged readers to burn their video nasties, ‘for the sake of ALL our kids’ (see Figure 1.1), while inside, the ‘chilling links between James’ murder and tape rented by killer’s dad’ were outlined (The Sun, 25 November 1993). A cartoon later that week was even more explicit – two boys ‘being led away’ by Chucky, the demonic doll from the Child’s Play series, in an apparent pre-play of the security video showing James’ abduction (see Figure 1.2). That the cartoon positioned Thompson and Venables in the position occupied by James in the security video functioned to displace the killers’ responsibility for their actions. Chucky – an American import – became a convenient scapegoat, diverting attention from the sociocultural environment in which the boys lived and in which kidnapping and killing James became both possible and meaningful to them.

Despite The Sun’s certainty that a video bonfire would protect us from future boy killers, there was no evidence that Thompson and Venables had even seen Child’s Play 3 and police investigating the murder consistently denied any link. Indeed, in a thoughtful account of the controversy, David Buckingham (1996: 35) demonstrates that the ‘chilling links’ The Sun reporters perceived between representation and reality were, at best, extremely tenuous and, at worst, completely misrepresented the film. Moreover, tabloid accounts confusingly suggested both that the killers themselves identified with Chucky and that they identified James with Chucky. If Thompson and Venables were indeed acting out the events of Child’s Play 3, then these reports where far from certain which roles they were playing. Despite (or perhaps because of) the lack of evidence connecting James’ murder to Child’s Play 3, the link made by the judge and embellished by the tabloids was to fuel more general concern about video violence. The relationship between text and action was presented with less and less circumspection as the story developed so that, as Buckingham (1996) notes, later news stories referred to this case as unequivocal ‘evidence’ that violent videos cause violent behaviour.

Figure 1.1 A simple solution to a complex problem: The Sun urges readers to burn their video nasties in the wake of the James Bulger murder trial (25 November, 1993).

Figure 1.2 The demonic doll, Chucky, leading the killers of James Bulger to their fate (The Sun, 27 November, 1993).

The stirrings of moral panic in the press were all too familiar to commentators who witnessed similar press-fuelled hysteria over video nasties in Britain in the mid 1980s (Barker, 1984a). Moreover, as with this earlier panic, there was an almost immediate rush to legislate against the living-room menace. This came to a head in April 1994 when a report commissioned by David Alton MP to support proposed far-reaching restrictions to the availability of home videos was published to great fanfare (Newson, 1994). Using the murder of James Bulger as the starting point for her investigation, the author of the report – Elizabeth Newson, a child psychologist with no record of research on media violence – condemned video violence as a form of ‘child abuse’. Newson suggested that in films like Child’s Play 3, the viewer identifies with the perpetrator of violence – an interesting claim in light of the tabloid confusion over the ‘chilling links’ between original and copy and one that contradicts much of the research on identification processes (see Chapters 2 and 5). Nevertheless, the report received extensive media coverage, dissenting voices were barely heard and the pressure on the Conservative government to ‘do something’ increased. For those who accepted the link between the murder of James Bulger and Child’s Play 3, the ‘something’ to be done was in many ways obvious: these videos must be censored, contained and controlled. In this context of panic and misinformation, an amendment to the Video Recordings Act was passed, stipulating that in awarding certificates to films on video, the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) must consider the potential for harm to viewers (and to underage viewers in particular) watching in the home.1

Six years later and thousands of miles from Liverpool, two teenage boys walked into Columbine High School armed with semi-automatic handguns, shotguns and explosives. After killing 13 people and injuring many more, the boys turned their guns on themselves. As the news media tried to explain the massacre, possible links between (other) media representations and the boys’ actions became the focus of much speculation. Films such as The Matrix and The Basketball Diaries came under attack simply because their characters’ long trench coats and choice of weaponry mirrored those adopted by the Columbine killers. However, whether or not the boys had even seen these films was never clear. The killers’ enjoyment of the nihilistic music of Marilyn Manson, their Internet usage and interest in computer games also generated considerable debate. Yet, as Michael Moore suggests in the award-winning Bowling for Columbine (2002), there is no inherent reason for these particular aspects of the boys’ lives to have come under such intense scrutiny. The boys also went bowling on the morning of the murders, but no one suggested that there was a link between these two activities, despite the fact that similar claims are made about contentious media texts on precisely this basis. At most, we might argue that this case suggests there might be a correlation between media and real-world violence – that is, that those who are violent in real life also consume violent media. However, it is important to emphasise that this does not prove a causal relationship between the two terms.

To emphasise this last point, I want to turn to a report in The Sun a few months prior to the Columbine massacre. Sensationally headlined ‘BOYS KILL FIVE THEN EAT PIZZA’ (2 December, 1998), the report describes how two teenage boys, ‘massacred five people for kicks after watching video nasties’. While the article goes on to suggest a causal link between ‘video nasties’ and murder, no one would seriously suggest that there is a causal link between murder and pizza eating. Rather, the juxtaposition of murder and pizza eating is supposed to tell us something about the killers (their lack of remorse, callousness and so on). Yet, on the basis of the evidence offered, the ‘murder causes pizza eating’ hypothesis is as plausible as the ‘viewing video nasties causes murder’ hypothesis. All we are told is that one event followed the other, just like killing followed bowling in the Columbine case. However, we are so used to video nasties being linked to murder that this lack of evidence is not glaringly obvious.

Surveying the coverage of the Columbine massacre, contradictory accounts of the relationship between the boys’ actions and their media consumption emerge. As in the Bulger trial, some reports attempt to establish a direct causal link between the crime and a specific media text (The Basketball Diaries, The Matrix, the music of Marilyn Manson). Many commentators focus particularly on the nihilistic lyrics and gothic, androgynous – and, crucially, different and recognisable – style of Manson and his fans. However, taken as a whole, the sheer variety of potential media influences cited in reports of the Columbine massacre surely demonstrates the impossibility (and absurdity) of trying to identify any one representation as the cause of the boys’ actions. Yet, these accounts consistently attempt to distance the shooters from ‘normal’ boys and adults and isolate these ‘dangerous’ texts from other cultural products. For example, Senator John McCain, chairing a Senate hearing on ‘Marketing Violence to Children’ in the wake of the massacre, suggested that a ‘rising culture of violence is engulfing our children’.2 Quite why this culture should engulf only ‘our children’ – leaving ‘us’ immune – is unclear, unless we accept that children (unlike adults) are passive, uncritical viewers or that children’s and adults’ media are entirely separate.

Proposing a rather different model of children’s viewing, media scholar Henry Jenkins (1999) suggested at the same hearing that we should be asking ‘what our children are doing with media’ rather than what media texts are doing to them. That Jenkins’ perspective was infrequently reported is perhaps not surprising as it complicates policymaking no end: if the media are not the violent agents then there are no easy, censorious solutions to the problem of children’s violence.

As this brief discussion has shown, in both the Columbine and Bulger cases the evidence linking the crimes to media representations was tenuous at best. Yet it is striking that the legitimacy of the media effects question – whether posed by the judiciary (as in the Bulger case) or the press (as in the aftermath of Columbine) – is commonly accepted. Those who try to respond to the question (like Newson in the Bulger case) often have very little knowledge either of the individual cases or of the huge body of research into media/violence, yet rumour and opinion quickly take on the status of ‘truth’ and ‘authority’. Press coverage thus polarises and over simplifies the debate, as you can either accept that Child’s Play 3 caused Thompson and Venables to kill James Bulger, or be forced into a position of arguing that the media has no influence. A middle ground is hard to find. Yet surely we should be asking how these boys’ media consumption – throughout their lives and not just in the immediate run-up to their crimes – reflected and reinforced their conceptions of themselves as boys/men and their understanding of violence. This question, however, demands that we look beyond the ‘bad object’ (video nasties) to examine texts that we ourselves may invest in and enjoy. It thus demands that we see the connections between those murderous boys and ourselves.

Moreover, these media-blaming accounts routinely ignore the one thing the killers of James Bulger and the Columbine High School shooters really do have in common: they are all male. Can this fact really be incidental or is blaming the media a way of not blaming boys and men? Answering this question requires that we look beyond the Bulger and Columbine cases and, in the remainder of this section, I present the findings of new research into the representation of media effects stories in the British press.

For this study, I examined all reports suggesting a causal link between a real-life act of violence and a specific media representation over a ten-year period (1990–99) in five of the most popular British tabloids and broadsheets.3 I identified 92 separate cases where one or more of the papers presented an allegedly causal link between ‘media’ and ‘violence’.

Given the import of such cases in shaping public opinion and policy, this may seem like a very slight figure. Certainly, claims about the relationship between media and real-life violence are far more visible than this figure would suggest, with the most high-profile cases – such as the Bulger murder – receiving extensive coverage. However, it is not only these high-profile cases in which such a link is made. During the 1990s, the British press laid the blame for various kinds of violence – spree shootings, armed robbery, serial killing, drug-assisted sexual assault and wre...