![]()

PART I

Change and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

![]()

1 The Dynamics of Change

The idea of change is fundamental to all the psychotherapies – it is their reason for being. However, from the point of view of psychodynamic therapy, change is not a straightforward issue. As an approach it is acutely sensitive to the difficulties, complexities and paradoxes that beset the therapeutic enterprise. Psychodynamic theory is distinguished by its vision of human life as problematic and conflictual – and this is no less true of therapy. In seeking to promote change, few things are pure and simple.

This outlook is true of psychodynamic theory itself. It is characterised by different perspectives and competing models. It has also changed in many ways in the course of its evolution. The complexities of the issues that it addresses are reflected in the intricate and sometimes elusive conceptualisations to which it has given birth. What they hold in common is the idea that individuals exist in a state of tension with themselves, other people and the world in general. The development of the psyche and of emotional difficulties has its foundation in the ways in which this struggle is worked out. It is this ‘dynamic’ character that marks human existence and which suggests that although change is the business of therapy, it is not an idea that can be taken for granted. In a sense, change is as problematic as staying the same!

The aim of therapeutic change

What exactly counts as ‘change’ in psychotherapy? At first sight this might seem unproblematic. As a therapy its aim must be healing and the alleviation of suffering through the removal of the symptoms or problems that lead people to seek help. Psychodynamic therapy arose out of this ‘medical model’ of change: the aim was the removal of symptoms through the correction of their underlying pathology. As the complexities of psychological change became clearer so too did the problems of maintaining this vision of the psychotherapeutic process.

One difficulty is establishing exactly what the end point of change, its goal and so its direction, might be. ‘Normality’ has a poor reputation these days with its overtones of social control and intolerance of difference. Other terms, such as ‘maturity’ or ‘mental health’ fare little better. Fleshing out the details of such ideals is only possible within a particular socio-cultural situation and its context of values. For his part, Freud famously referred to the ability ‘to love and to work’. However, the psychodynamic tradition has been reluctant to stay at the level of external rather than inner – psychological – descriptors of change. One reason is its therapeutic focus on subjectivity and the inner world of experience. But there has also been the belief that external behavioural criteria of change are typically too specific, localised and perhaps minor to be the most important therapeutic goals. They are seen as superficial in relation to the diffuse and extensive difficulties for which people commonly seek psychotherapeutic help. There is a wish by many therapists and clients to look deeper – to seek more fundamental ‘structural’ change in the personality.

An important reason for seeking structural change is the idea that in addition to being more pervasive, it will also be more permanent. Change in relatively superficial behaviour patterns is thought likely to be temporary, vulnerable to changing circumstances and subject to reversal. Although therapeutic changes can be rapid, even dramatic, psychodynamic therapists have come to suspect that rapid progress can also be unstable and almost equally transient. Efforts have thus been focused on working steadily for the long term. Even short-term psychodynamic therapies seek to start a process of development that is consolidated on a longer time scale. Such gradual progress, however, is not necessarily built incrementally and continuously. Because a dynamic vision suggests that psychological structure is a delicate balance of competing forces, the process of change is not likely to be linear: it involves reversals and regressions, plateaux with little progress and sudden breakthroughs to a qualitatively different level. Indeed, one definition of psychological ‘pathology’ might be when this balance is maintained in a rigid, inflexible way. The ability to change, to respond flexibly to life’s circumstances in adaptive and creative ways is probably a good psychodynamic definition of a healthy state of being. The capacity for further change thus becomes the goal of change in psychotherapy!

There is high ambition in these aims of enduring structural change which has meant that psychodynamic thinking has always been drawn to the grand themes of life: personal transformation, fundamental meaning, creation and destruction, birth and death, even the origins of society. Therapies with a more modest outlook typically take a more pragmatic view and build their theories to serve more restricted ends. But this grappling with the major issues in human life is one of the strengths and the attractions of the psychodynamic outlook: it attempts to encompass a vision of life. This vision – along with the definitions of psychological structure in which it is framed – varies greatly between theorists. For Freud it had quite an austere aspect: maturity is about facing what is painful and unacceptable in ourselves; our problems are not just about bad things happening to us but about our own questionable motives; life is intrinsically problematic and unsatisfactory and we should value above all such virtues as restraint, patience, fortitude and unflinching honesty. This stoical element in Freud’s vision (we might say in his character) is represented in his well-known comment to a patient that much would be gained if they transformed her ‘hysterical misery into common unhappiness’ (Breuer and Freud, 1895: 305).

However, this vision can be translated into aims that seem less bleak. Indeed, Freud did go on to suggest to his patient that she could become ‘better armed against the unhappiness’. The emotional repertoire that enables someone to lead life well includes acceptance of the wishful, painful and conflictual aspects of our personalities, so that we can become better friends with ourselves (and so with others). It also involves finding a new immediacy and intensity in living and better ways of dealing with life’s continuing challenges. Psychological difficulty arises from the avoidance of these problems in living in ways that stultify our own potential. Psychotherapy’s aim, then, is to enable us to develop capacities that free our potential for inventiveness and pleasure in life.

In articulating these ambitious goals for itself, the psychodynamic tradition seems to have swayed between optimism and pessimism. Particularly in the early days there was an idealised vision of what could be achieved by the processes of psychotherapy and the knowledge gained from it. Towards the end of his career Freud (1937) had formed a more pessimistic view: the intractable difficulties in human life and our frailties as individuals made psychoanalysis (together with those other specialisms in human change, education and government) an ‘impossible profession’, always destined to achieve unsatisfactory results. Perhaps this ironic comment is best taken as a necessary corrective to the tendency – still present – to idealise any form of psychotherapy.

The tasks of psychotherapy

From the psychodynamic point of view, most emotional suffering is extensively and intricately connected, in ways that the person does not perceive, to other aspects of the way they live. This challenges any simple view of personal problems and how to change them. It also alerts us to the ambivalence that people generally have about changing. Someone in pain of course wants to be free of it and of the restrictions by which they feel trapped. But people also fear change: they fear the loss of security and familiarity in what they know. In coming into therapy, they often fear losing themselves and becoming someone else. Attention to this element of unwillingness and difficulty with change – the client’s ‘ambivalence’ and ‘resistance’ – alerts us to an ambiguity in understanding what she1 (or anyone) wants. Since much of this ambivalence and resistance is not directly in the field of awareness – is ‘unconscious’ – these obscure and contradictory motives will inevitably be brought into therapy. The client wants ‘help’ to be sure but what exactly is that in her mind? There is a profound irony that because of the way unconscious motives are brought into the therapeutic situation, the kind of help that clients imagine getting from a therapist often turns out to be just more of the same old stuff! The problems which they want solved are replicated in the way they imagine them being tackled: someone who tends to depend too much on others for direction seeks a confident advisor; someone who is cut off from their feelings and over-intellectualises seeks an expert to discuss things with, and so on. Thus in the psychodynamic view, while change may be on offer, it is usually not – and should not be – quite what the client may think is needed. Nor indeed should the therapist presume to know what it should be. Exactly what will be helpful remains to be discovered in the course of the therapeutic work.

While this may reflect appropriate humility, it leaves the therapist in an uncertain position with regard to her role as an agent of change. The solution to this has been a radical one: the fundamental stance of the therapist should not be to try to ‘cure’ or directly change the client. Psychodynamic therapy is not a ‘repair shop’ in which people are straightened out. Instead, the task is to seek understanding – to attempt to describe rather than to alter things directly. If a client’s awareness is extended, it is reasoned, this increases her freedom and capacity to choose. If a therapist actively seeks change, this offers a vision which functions as a demanding ideal: some bits of the client are good, others bad (which is, of course, what most clients already feel). In some psychoanalytic thinking this approach has been taken to extremes. It has been suggested that the therapist should have no aim other than to ‘analyse’ – change is just a byproduct. In a sense, this is a piece of wise nonsense. Underlying it is the appreciation that a preoccupation with aims can hinder effectiveness. The therapist must not need (rather than hope) to help the client. On a session-to-session basis, not being beset by therapeutic ambition enables the therapist to find the appropriate state of mind, one in which she is not confused by and drawn in to what one part of the client may insist is wanted.

This stance places a premium on the responsibility of the client. Psychodynamic therapy attempts (in spite of some past tendencies to the contrary) to enable clients to retell their story in terms of the intentions they have and the choices they make. Of course, most forms of psychotherapy are premised on the value of clients taking responsibility for their lives and the need for therapists not to impose their own values. The difference in the psychodynamic approach is its special sensitivity to the ways in which therapists do in fact influence clients and, crucially, the ways in which clients will lead therapists to take responsibility for their difficulties. The therapeutic approach thus endeavours to embody a deep respect for the client’s autonomy, something that is fostered by the therapist’s reflective rather than directive stance, sometimes at the cost of considerable frustration for the client! The therapist tries not to relieve the client of her responsibility by leaving the possibilities for change as open as she can.

Nevertheless taken to an extreme, the notion of having no aims or responsibility for change is rather a defensive point of view that can be used to deny legitimate questions about the effectiveness and appropriateness of a dynamic or ‘analytic’ approach to a therapeutic need. There are different levels of aim and a constant interaction between them. A vision of a long-term outcome for this client – who she might potentially become – is always somewhere in the therapist’s mind and it is futile to pretend to dispense with it (Sandler and Dreher, 1995). It inevitably informs the ‘process’ decisions of what to do and say in particular sessions and the more specific process aims that lie behind them. As psychodynamic therapy developed there was an increasing emphasis on these process considerations; principally because experience taught that the means were as important as the ends and, to effect lasting change, the ends could rarely be approached directly.

Change and the process of therapy

The overall format of therapeutic practice encompassed within the psychodynamic tradition is enormously variable. It extends from brief once weekly therapies (10–25 sessions), or even consultations of just a few sessions, through to intensive long-term work, with several sessions a week extending over many years. Clearly, the therapeutic aims should be appropriate to whatever constraints may be imposed by the client, the therapist’s training or the context of practice. A distinction is commonly made here between analysis and therapy. However, this is a demarcation that is often driven by professional politics and issues of status. The criteria suggested to define the difference turn out to vary greatly. External markers are the intensity and length of the expected contract and the use of a couch as opposed to face-to-face seating. More ‘internal’, process-oriented criteria have also been proposed, particularly the rigour with which the therapist holds to a neutral, interpretative posture rather than pursuing some form of explicit therapeutic change. Other internal criteria suggest that it is the quality of the client’s engagement with the therapist in the task of self-understanding that is crucial. The nature of the relationship and the therapeutic atmosphere that particular client/therapist pairs construct between them varies considerably whether or not they meet these criteria. We consider the analysis/therapy distinction rather unhelpful, indeed untenable in practice. All therapeutic contracts seek change. Goals vary in ambition and different individuals require different ‘techniques’ to achieve them, so the therapist’s posture needs to adjust depending on a whole range of factors. Some judgements about what is appropriate can be made more or less easily and reliably early in the therapy, and so affect the form of the initial contract; others only emerge in the experience of working together.

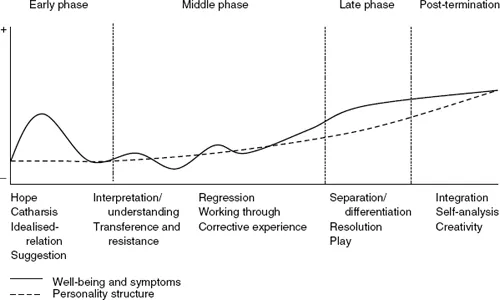

Figure 1.1 Idealised course of psychodynamic psychotherapy (adapted from Wolberg, 1977)

For the purposes of getting an overview it is possible to propose what might be called an average expectable course of therapy, with particular issues associated with different phases of the work (see Figure 1.1). At the start of most therapies, there are a number of non-specific influences that make for an encouraging and supportive experience. These include: the hope of relief, an idealised relationship with the therapist, an element of ‘suggestion’ in the implication that all will be well, and the relief provided by emotional expression. Some clients leave during this first flush of well-being and some, with their own energy remobilised, may maintain that improvement. But no underlying change will have taken place. For those who continue, this honeymoon period will end sooner or later: the problems recur. The therapist is not as wonderful as previously thought, the commitment is a lot to ask and so on. If the client sticks with it at this point, the real work begins.

As the client’s ambivalence and resistance to self-awareness and change emerges explicitly and is confronted, it is quite likely that old (or new) problems will erupt. Anxiety or depression increase and the experience of being involved in a real and painful struggle has to be borne. If the client drops out in this middle phase she is likely to feel little benefit. The therapist provokes changes by disturbing the client’s usual patterns of relating and of understanding herself. To be affected by the therapy she needs in some degree to be unsettled, challenged, even shocked. It is this that gives rise to the old saying that you have to get worse before you can get better. Crises and breakdowns in the accustomed ways of being are looked to as opportunities to break through to a new more flexible level of equilibrium. Disturbance is necessary – but not too much; the client also needs support from the therapist in order to bear it. However, in psychodynamic work, by challenging defences and enabling clients to confront themselves, the therapist inevitably stimulates some emotional pain.

If the work proceeds well, all the psychodynamic processes of change with which this book is concerned may come into play. The client enlarges her experience in a way that enables her to understand and master emotions, widening her choices and supporting her to give up old securities and the fringe benefits of her ‘illness’ to experiment with new forms of relating, to herself and to others. In the final phases, the client must start to give up the dependence that she may have developed on the therapist and deal with issues of separation and loss, hopefully internalising not only specific understandings gained but the processes of self-awareness and self-containment. Indeed, the process of change is not finished with the end of therapy. The personal capabilities that have been acquired can consolidate and further extend in their subsequent influence on life-experience.

Of course, no specific therapy should be expected to follow such an idealised course. It is not useful to homogenise the psychodynamic therapies in all their variety into an imagined single process. However, spelling out this simplified model of therapeutic progress enables us to see the work as a whole, something which is not always easy to do when in the midst of it. Even short-term therapies typically pass through a number of phases not dissimilar to this, albeit in a compressed form.

The client’s experience

The client’s experience of therapy, as might be anticipated from the process outlined above, is rarely easy or smooth. She might well feel a good deal of puzzlement or frustration that the therapist does not respond to her in the ways that she would have expected. The client might have hoped for more comfort and reassurance than seems to be forthcoming. It might even seem as though the therapist has answers that are wilfully withheld. Even as new understandings of her situation emerge, she is left to decide what to do with them rather than receiving the guidance that is often hoped for. Indeed, her very hopes for change might be held up for questioning. It can be a disorienting experience – and it can get worse!

As accustomed ways of handling distress, avoiding disturb...