![]()

1

The picture we create: explanations and levels

- Identifying difficult behaviour

- Explaining difficult behaviour

Typical everyday explanations in school

Effects of ‘inside the person’ and ‘outside the walls’ thinking

Improving explanations

Changing the discourse

- Contexts and situations

A multi-level view of behaviour

Improvement at all three levels

- Principles of improving school behaviour

Being proactive

In this chapter we set out key ideas for the rest of the book. We start by considering the way in which behaviour difficulties are viewed in school, and how they are explained to self and to others. Common everyday explanations are analysed, and the disempowering effects on teachers are discussed. We then present practical alternatives, which also help colleagues in a school discuss the patterns of behaviour at three important levels: the organizational level, the classroom level, and the individual level. We look at the research evidence which indicates that improving school behaviour must mean working at all three levels.

Identifying difficult behaviour

It is important to start by recognizing that different perspectives on what constitutes difficult behaviour exist in our schools. This is not some simple matter of sloppy subjectivity or relativism: it is a fact of social life. We find that a small proportion of teachers do not like this point: they say that it introduces unnecessary complications and remark ‘Why don’t we just agree on what behaviours are difficult and what we’ll do to deal with them’. Our reply is that we have seen groups of teachers in schools do that time and again, and either end up in conflicts or with little change occurring. The reason is that such agreements paper over real variations, some of which will always exist and can be used profitably for improvement. As we will see in Chapter 2, the dressing up of such agreements as ‘school policy’ has little positive effect in the majority of circumstances.

The diversity of views on school behaviour which are to be found in, around and across school staffrooms is not something we wish to bemoan. Though we accept that in a few schools there is too little commonality between teachers, this usually betrays some other major difficulty or conflict in the school. Most times the diversity is appropriate, and can be a source of learning. Our view is that it is important for teachers to identify and discuss their different ways of seeing, but not to aim for some unrealistic consensus. It follows that we do not expect progress will follow from us (or anyone else) advocating a single definition for difficult behaviour.

Take any behaviour you like, which you think people would agree was difficult or deviant in a particular situation: you can always think up another situation in which it would not be seen as such. Whether a particular act is regarded as deviant varies in a range of ways, including those which follow.

- According to place. In school Mary’s singing may be viewed differently in the art room, in the music room, in the head’s room. What Mary does outside the school gates may be perceived differently from the same action inside. Across different schools, what a pupil may do acceptably in one may be completely unacceptable in another.

- According to audience. Nigel’s critical comment about a teacher while discussing his behaviour with his tutor will probably be seen differently from the same comment made while his tutor is teaching the form. When an inspector becomes an additional audience in the classroom, both pupils and teachers change their behaviour. When visitors tour a school, an additional or accentuated set of rules for what is acceptable is often activated: ‘best behaviour’.

- According to the actor. Linda has a reputation for disrupting lessons: her behaviours may be seen and responded to differently from the same behaviour by classmates who do not have such a reputation. A Year 7 pupil with unexplained absences may be perceived differently from a Year 11 pupil. Denise’s direct physical aggression may be seen as more deviant than Denis’s. A pupil arguing with teacher may be seen in various ways, perhaps depending on whether the pupil is a child of a lawyer or of a bricklayer. John’s behaviour in the corridor is viewed as ‘over boisterous’, but similar behaviour from Joel who is Black British is perceived differently.

- According to the observer. Mrs Williams has seen John pushing in the dinner queue three times before: she sees things differently from Mrs Jones who has not. Mr Frederick has a real concern about bullying: his reaction to events differs from that of his colleagues.

- According to who is seen as harmed. Andrew taking a ruler from his friend in the same year is viewed quite differently from him taking a ruler from a pupil in the earlier years. Ann jostles people in the crowded corridor: this is viewed as ‘playful’ towards her apparent friends but not towards Maria in her wheelchair.

- According to time. Steve’s shortage of equipment for lessons is seen in a different light when the school has a ‘purge’ on equipment: similarly for ‘drives’ on homework or attendance or uniform. Hassan’s exuberance is perceived differently on Monday morning than it is on Friday afternoon. The perception of Julie’s talking at the beginning of the lesson is different from that of her talking at the end.

So, identifying difficult behaviour is not a matter of simple definition. Instead our attention is drawn to variations in contexts and variations in explanations.

Explaining difficult behaviour

Typical everyday explanations in school

When attempting to improve school behaviour we soon come face to face with the explanations for difficult behaviour which circulate in a school, their variety and any prevalent explanations or trends. These explanations can have a significant effect on improvement attempts – for good or ill. Teachers’ explanations reflect, in part, real evidence about patterns of difficulty: they also reflect a range of distortions or partial perspectives. We will examine five broad explanations which we have encountered in our experience of schools, and which are sometimes referred to in the literature. We use the broad everyday phrases and offer a range of examples:

- ‘They’re that sort of person’

- ‘They’re not very bright’

- ‘It’s just a tiny minority’

- ‘It’s their age’

- ‘This is a difficult neighbourhood’.

As we discuss each in tum, you might think of examples which you hear in school, and also consider the impact of their use.

‘They’re that sort of person’

Examples such as ‘Jeremy is an aggressive boy’ serve to show how this way of talking attempts to package everything about difficult behaviour into some feature of the person. It is classic ‘within-person’ thinking. ‘He’s a special needs kid’, someone remarked, as if the analysis should end there. We are not saying that this sort of talk is always making negative evaluations of the pupil in questions: one memorable one was ‘Ah but you have to understand that this pupil has Bohemian parents’, and the speaker was not referring to a new refugee group but was wanting to explain the behaviour difficulties by recourse to family attitudes. Of course there are broad trends which link family attitudes to performance at school, but these cannot be simply invoked in an individual example. In a similar way, the use of prevalent stereotypes about single parents or separated and reconstituted families ignores the great range of ways in which families respond to and cope with such conditions, and so does not offer an adequate explanation in the individual case. Examples which contradict the ‘family background’ explanations are regularly found in school, but such evidence is often resisted:

Some teachers expressed astonishment when pupils were exceptionally resistant to teacher influence despite an apparently supportive home background. They were equally surprised if model pupils were inadvertently revealed to live under adverse home circumstances. Faced with a rebellious or uncooperative pupil, teachers were often prepared to assume that there be something wrong at home even if no evidence was immediately available.

(Chessum, 1980, p. 123)

A similar simplification is that which assumes that a pupil’s behaviour at school mirrors behaviour at home. Interesting light is thrown by the findings which showed that when teachers and parents completed similar rating scales for the same children there was comparatively little overlap between the ‘disorders’ perceived by both groups (Graham and Rutter, 1970). So, even if teachers were identifying a similar overall percentage to that of surveys, and attributing family explanations, they may be identifying a different group of children from that identified by parents! The behaviour which pupils display in school is not a simple reflection of their behaviour elsewhere, including at home (see, for example, Rutter, 1985a). In the case of those pupils where the conventional wisdom is that their behaviour varies less than most according to situational cues, i.e. pupils categorized as having severe learning difficulties, just under half are reported to have challenging behaviours both at school and at home, and the particular behaviours displayed and seen as challenging are different in each context (Cromby et al., 1994).

Nor is behaviour at secondary school a simple continuation of behaviour at primary school. Secondary schools with poor pupil behaviour are not simply those which receive a high proportion of pupils with a record of behaviour problems at primary school (Rutter et al., 1979). ‘There was only a weak relationship between behaviour at primary and secondary schools’ (Mortimore, 1980, p. 5).

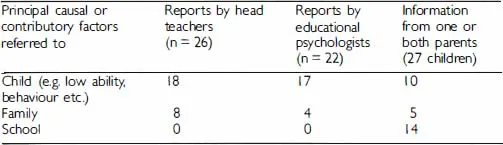

The ‘they’re that sort of person’ view seems to be an attempt at explanation, but at the same time seems to reflect some powerlessness in the teacher’s attempt to understand – ‘they’re just like that’ (and I cannot say any more). Nevertheless the use of this explanation can have action implications: for example, if the pupil’s behaviour is disturbing, then this explanation may be used to justify a referral to whoever is supposed to deal with ‘that sort of person’. Those case-based professionals who sometimes practise with an individualistic view of people are then engaged, and in this process their ability to ‘fix’ certain individual problems is mistakenly overestimated, sowing the seeds for teachers’ subsequent disappointment at their offering. Within-child explanations are much more a feature of reports by headteachers and educational psychologists (Table 1.1), than they are of interviews with parents (Galloway, Armstrong and Tomlinson, 1994).

TABLE 1.1: Explanations of heads, psychologists and parents

Source: Galloway, Armstrong and Tomlinson (1994).

‘They’re not very bright’

This teacher explanation could be seen as a variant of the previous one, but it deserves special attention since it brings to the fore beliefs which are particular to school contexts and to pupil attainment. Judgements about pupil ‘ability’ have an extra significance in the school context and are closely connected with the way school is organized: in some schools beliefs about fixed ability circulate regularly, in others less so. When related to difficult behaviour, we can hear examples or variations of these: ‘Some of these disruptive kids try to hide the fact that they can’t get on with the work by creating diversions’ or ‘ They get frustrated with the work and then start to mess around’. A moment’s thought clarifies that this explanation embodies significant beliefs and assumptions on the part of the speaker regarding classrooms, curriculum and school. These assumptions often imply what can change and what cannot. If they lead to a more detailed examination of how to modify the curriculum or the classroom context in ways which engage such students, all well and good. In contrast, to accept such an explanation in a fixed form would imply that pupils of particular ‘abilities’ will be disruptive. Such an alternative is unacceptable. The explanation ‘if they’re not very bright, there’s nothing we can do about it’ is a recipe for a passive response rather than an improving response, because it embodies a notion of innate or fixed abilities rather than one of learning potential. A way forward is more likely to come from considering how pupils of all current attainment levels can be engaged in learning.

‘It’s just a tiny minority’

This explanation recognizes that there may be a pattern in the numbers of pupils involved, but locates the cause in a very small number. Many social systems contain beliefs that their dangerous miscreants are small in number but have a disproportional effect because of contagion effects: one rotten apple can spoil the whole barrel, etc.

It can be useful to reflect on what ‘tiny’ is. Evidence from in-school surveys has indicated up to 15 per cent of the pupils on roll are mentioned by name in connection with disruptive incidents monitored across two terms (Lawrence, Steed and Young, 1977). Hardly a tiny minority. Nor even the ‘hard core’, because although only 1 per cent of students were mentioned in incidents from both of the weeks monitored, these were only a small proportion of the incidents which staff viewed as serious, numbers of which involved large groups of pupils. So a picture emerged of more general disruption with a varying group of pupils involved, making it more profitable to examine the patterns of pupil roles (see Chapter 3) than to locate the cause in one or two individuals.

Another feature of the ‘it’s a tiny minority’ explanation is the implication that ‘tiny minorities’ are distinctly different from ‘us’ (who, of course, are part of the majority): they are portrayed as obeying very different rules (or no rules) and are so different (from us) that it is unlikely we would be able to understand them. Thus, the accentuation of differences is achieved, and if there were any real differences they are greatly exaggerated. A good antidote to this trend is to help teachers remember their histories – some of them were skilled disrupters – or to have them simulate a classroom and have the roles emerge. Disruptive pupils are not an inherently different group but the pressure to portray them that way seems strong.

The action implication of the ‘it’s only a tiny minority’ explanation is to identify them (‘early’ if possible) and extract them. ‘If we get rid of the troublemakers, everything will be all right’. But that is no solution in the long run. Unless such separation is strictly temporary, the facility for separating pupils will tend to ‘silt up’. It also works once only: when it is full, schools continue to want to refer to the provision they have become accustomed to, and meanwhile in the classroom, new members have emerged to fill the deviant roles of those who were removed. ‘Pressures build up within (the schools) for more provision, which is then created – and soon fills up, and so on. In this way many problems of behaviour are apparently coped with, more are created, fewer are solved’ (Rabinowitz, 1981, p. 78).

This is the sort of partial thinking behind the provision of ‘pupil referral units’ in England and Wales in the 1990s. There are always more procedures for processing pupils into these units than there are for processing them out, so the provision fills up, contrary to the official protestations that this was meant to be short-term provision. It also grows: a survey we completed in 1995 (unpublished) found some units with over 200 pupils on roll. The vast majority are told to attend...