![]()

| 1 | Origins of Creative Industries Policy |

Introducing Creative Industries: The UK DCMS Task Force

The formal origins of the concept of creative industries can be found in the decision in 1997 by the newly elected British Labour government headed by Tony Blair to establish a Creative Industries Task Force (CITF), as a central activity of its new Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The Creative Industries Task Force set about mapping current activity in those sectors deemed to be a part of the UK creative industries, measuring their contribution to Britain’s overall economic performance and identifying policy measures that would promote their further development. The Creative Industries Mapping Document, produced by the UK DCMS in 1998, identified the creative industries as constituting a large and growing component of the UK economy, employing 1.4 million people and generating an estimated £60 billion a year in economic value added, or about 5 per cent of total UK national income (DCMS, 1998). In some parts of Britain, such as London, the contribution of the creative industries was even greater, accounting directly or indirectly for about 500,000 jobs and for one in every five new jobs created, and an estimated £21 billion in economic value added, making creative industries London’s second largest economic sector after financial and business services (Knell and Oakley, 2007: 7).

The UK Creative Industries Mapping Document defined the creative industries as ‘those activities which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have the potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property’ (DCMS, 1998). The Creative Industries Mapping Document identified 13 sectors as constituting the creative industries, shown in Table 1.1.

In launching the Mapping Document, the Minister for Culture and Heritage, Chris Smith, made the observation that:

The role of creative enterprise and cultural contribution ... is a key economic issue. ... The value stemming from the creation of intellectual capital is becoming increasingly important as an economic component of national wealth. ... Industries, many of them new, that rely on creativity and imaginative intellectual property, are becoming the most rapidly growing and important part of our national economy. They are where the jobs and the wealth of the future are going to be generated. (Smith, 1998)

Table 1.1 DCMS’s 13 Creative Industries Sectors in the UK

| Advertising | Interactive leisure software (electronic games) |

| Architecture | Music |

| Arts and antique markets | Performing arts |

| Crafts | Publishing |

| Design | Software and computer services |

| Designer fashion | Television and radio |

| Film and video | |

Source: DCMS, 1998.

This theme that creative industries were vital to Britain’s future was a recurring one for Labour under Tony Blair and, from 2007, Gordon Brown. Tony Blair observed that his government was keen to invest in creativity in its broadest sense because ‘Our aim must be to create a nation where the creative talents of all the people are used to build a true enterprise economy for the 21st century – where we compete on brains, not brawn’ (Blair, 1999: 3). Chris Smith, in launching the second DCMS Mapping Document in 2001, argued that ‘The creative industries have moved from the fringes to the mainstream’ (DCMS, 2001: 3), and continuing work in developing the sector saw related policies being developed in areas such as education, regional policy, entrepreneurship and trade. This theme continued with the change in Prime Ministership, with Gordon Brown arguing that ‘in the coming years, the creative industries will be important not only for our national prosperity, but for Britain’s ability to put culture and creativity at the centre of our national life’ (DCMS, 2008a), although – as we will see later – the economic ground shifts very rapidly in Britain during the time of Gordon Brown’s Prime Ministership.

The DCMS mapping of the UK creative industries played a critical formative role in establishing an international policy discourse for what the creative industries are, how to define them, and what their wider significance constitutes. In Michel Foucault’s (1991b) classic account of discourse analysis, a discourse can be identified in terms of its:

| 1 | Criteria of formation: the relating between the objects identified as relevant; the concepts through which these relations can be comprehended; and the options presented for managing these relations; |

| 2 | Criteria of transformation: how these objects and their relations can be understood differently, in order to generate what Foucault refers to as new rules of formation (Foucault, 1991b: 54); |

| 3 | Criteria of correlation: how this discourse is differentiated from other related discourses, and the non-discursive context of institutions, social relations, political and economic arrangements etc. within which it is situated. |

In the field of policy studies, discourses are understood as ‘patterns in social life, which not only guide discussions, but are institutionalised in particular practices’ (Hajer and Laws, 2006: 260). In this way, as Foucault observed, relations between discourses and institutions, or between social reality and the language we use to represent it, become fluid and blurry. From a research point of view, policy discourse analysis enables one to get ‘analytic leverage on how a particular discourse (defined as an ensemble of concepts and categorizations through which meaning is given to phenomena) orders the way in which policy actors perceive reality, define problems, and choose to pursue solutions in a particular direction’ (Hajer and Laws, 2006: 261). Policy discourse constitutes a core element of what Considine (1994) refers to as policy cultures, or the relationship within a policy domain between shared and stated values (equity, efficiency, fairness, etc.), key underlying assumptions, and the categories, stories and languages that are routinely used by policy actors in their field, and help to define the policy community, or those who are ‘insiders’ within that policy field.

Understood in terms of policy discourse, we can see some of the central contours of the approach to creative industries adopted by the Blair Labour government and the DCMS in Britain as it emerged in the late 1990s. The new government took the opportunity provided by its election mandate and a large parliamentary majority to reorganise policy institutions. In this case, it took what had been the Department of National Heritage and reorganised it as the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, bringing the arts, broadcast media and (somewhat oddly in retrospect) sport together within the one administrative domain. But such an administrative change would have little significance if it had not been accompanied by a series of related discursive shifts. By bringing together the arts and media within a department concerned with the formation of culture, the Blair government was signalling a move towards more integrated approaches to cultural policy that have characterised European nations, rather than the more fragmented, ad hoc and second-order approaches to cultural policy that have prevailed in much of the English-speaking world (Craik, 1996, 2007; Vestheim, 1996). But the second, and perhaps more significant, discursive shift lay in the way that creative industries drew upon the then-new concept of convergence to argue that the future of arts and media in Britain lay in a transformation of dominant policy discourses towards a productive engagement with digital technologies, to develop new possibilities for the alignment of British creativity and intellectual capital with these new engines of economic growth. This association of creative industries with the modernisation project of Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ was strong, and is discussed in more detail below. The final key point was that creative industries promises a new alignment of arts and media policies with economic policies, and by drawing attention to the contribution of these sectors to job creation, new sources of wealth and new British exports, there would now be a ‘seat at the table’ for the cultural sectors in wider economic discourses that had become hegemonic in British public policy under the previous Conservative governments.

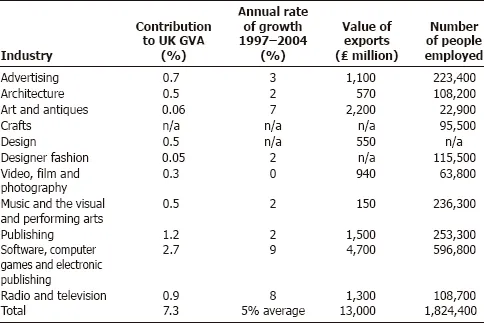

As a policy discourse, creative industries was itself a successful British export. Wang (2008) has identified the term ‘creative industries’ as a successful British marketing exercise, and Ross has observed that ‘few could have predicted that the creative industries model would itself become a successful export’ (Ross, 2007: 18). In the next chapter, we will consider the take-up of creative industries policy discourse in other parts of the world. What needs to be considered is how in practice the economic value of the creative industries was determined. While the definition of the sectors constituting the creative industries has evolved over time, a list-based approach to creative industries has remained a hallmark of the original DCMS model, where the overall size and significance of the creative industries to the UK economy has been taken to be measurable as the aggregate output of its constituent sub-sectors. Early documents were engaged with mapping the creative industries, but this was more a cognitive mapping than a geographical one, seeking to determine what the objects of creative industries policy were, what were their relationships with one another, and how to relate the measurement of their size and significance with the broader public policy goals which had now been enunciated for arts and media policy under the creative industries policy rubric. How this worked in practice can be seen from the Creative Industries Economic Estimates for 2004 data in Table 1.2 provided, which measured the size of the UK creative industries in terms of their contribution to national income (Gross Value Added – GVA), their average annual rates of growth, their contribution to exports, and the number of people employed in these industries.

Table 1.2 Economic Contribution of UK Creative Industries, 2004

Source: DCMS, 2007.

In an early commentary on this list-based approach, I described it as being ad hoc (Flew, 2002), as it was not clear what the underlying threads were that linked a seemingly heterogeneous set of sub-sectors as the creative industries. The categorisation draws together industries that are highly capital-intensive (e.g. film, radio and television) with ones that are highly labour-intensive (art and antiques, crafts, designer fashion, music, the visual and performing arts). It also combines sectors that are very much driven by commercial imperatives and the business cycle, such as advertising and architecture, with those that are not. From a policy point of view, the static economic performance of the UK film industry over 1997–2004 indicated by these figures would be a major concern to government due to the size of Britain’s audiovisual trade deficit with the United States, which is not compensated for by a comparatively strong performance in the art and antiques markets.

Critics of the DCMS approach such as Garnham (2005) argued that inclusion of the software sector in the creative industries artificially inflated their economic significance in order to align the arts to more high-powered ‘information society’ policy discourses. It is certainly the case from the figures above that the sector defined as ‘Software, computer games and electronic publishing’ accounted for 37 per cent of the economic output of the UK creative industries, 36 per cent of its exports, and 33 per cent of creative industries jobs; the question of its inclusion or exclusion bears heavily on wider claims made about the economic significance of the creative industries. As well as questions of inclusion, there are also questions of exclusion, with some asking why sectors such as tourism, heritage and sport were not in the DCMS list (Hesmondhalgh, 2007a). The exclusion of sport is interesting given that so much energy had been expended on bringing sport within the Department, but perhaps more telling is the reluctance to consider the economic contribution of what has come to be termed the GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums) sectors in these original policy documents. Since the economic value of Britain’s cultural institutions (British Museum, National Gallery, British Library, Tate Modern, Victoria and Albert Museum, etc.) cannot be questioned, one suspects that it reflected the modernisation drive of the Blair era to understand Britain in terms other than those of an ‘old country’ (Wright, 1985). Finally, there is a well-known paradox in trying to determine the size of the creative industries workforce. Many people working in those industries defined as creative industries are in jobs that would not normally be considered to be ‘creative’ ones (e.g. an accounts manager at an advertising agency), while there are others who have been termed ‘embedded creatives’ (Higgs and Cunningham, 2008) who are pursuing creative work in other sectors (e.g. website designers for a bank or financial services company). Many of these issues take us to the utility of the concept of creativity as a definer of industries and sectors, and these debates will be returned to later in this chapter as they have played themselves out in the British context.

Cultural Planners and Cool Britannia: UK Creative Industries Policy in the Context of ‘New Labour’

The creative industries concept maintained an ongoing relevance as a policy discourse in the United Kingdom from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s. This period was one of concurrent Labour governments in the UK, headed by Tony Blair from 1997 to 2007, and by Gordon Brown from 2007 to Labour’s electoral defeat in May 2010. It has certainly been the case in the English-speaking world that left-of-centre governments tend to adopt a more activist stance towards questions of cultural policy than conservative ones, but at the same time creative industries policies differed significantly from traditional cultural policy in their stronger focus on economic wealth generation, and the significance given to creative entrepreneurs and the private sector rather than publicly funded culture. Creative industries as a concept was consistent with a number of touchstones of the redefining of the British Labour Party as ‘New Labour’, as it was spearheaded by Tony Blair and his supporters within Labour, with its recurring concerns with economic modernisation and Britain’s post-industrial future. Its focus on the role of markets as stimuli to arts and culture was consistent with the notion of a ‘Third Way’ between Thatcher-era free market economics and traditional social democracy, which was nonetheless more accommodating of the role of markets and global capitalism than traditional British Labour Party philosophy and doctrine (Giddens, 1998). Promotion of the creative industries was also consistent with empirical realities of the late 1990s where ‘Britain’s music industry employed more people and made more money than did its car, steel or textile industries’ (Howkins, 2001: vii), and it marked out one response to the common theme of de-industrialisation facing the traditional manufacturing powerhouses of Western Europe.

Labour came to power in Britain after 18 years of Conservative governments, headed by Margaret Thatcher and John Major, that had relentlessly pushed the privatisation of state-run enterprises, user-pays principles for access to government services, a self-reliant enterprise culture, and a general devaluation of the role of the public sector in British economic and social life. This had been a particularly cold climate for the arts, with peak funding bodies such as the Arts Council of Great Britain feeling underfunded and beleaguered. Moreover, artists themselves had become targets for scorn in the popular media, with works that had a critical, counter-cultural or avant-garde element being routinely derided as a ‘waste of taxpayers’ money’. It had no longer been sufficient to defend the value of the arts in their own terms, and from the late 1980s onwards it had become common to argue the case for public support for the arts in terms of their economic contribution (Myerscough, 1988). While the shif...