- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Social Theory

About this book

"This is a robust text - challenging and provocative and one which students will benefit from reading. Layder guides the reader through a large body of relevant literature. He draws attention to the strengths and weaknesses of particular approaches as he sees them and he is not afraid to offer his own judgements on the issues and problems he addresses."

- Professor John Eldridge, University of Glasgow

"One of the most comprehensive, incisive and readable treatments of the macro-micro problem now available."

- Professor Paul Colomy, University of Denver

This is a revised, updated and enlarged version of the accessible, authoritative first edition - a jargon-free textbook that provides an introduction to the core issues in social theory. It includes:

- Professor John Eldridge, University of Glasgow

"One of the most comprehensive, incisive and readable treatments of the macro-micro problem now available."

- Professor Paul Colomy, University of Denver

This is a revised, updated and enlarged version of the accessible, authoritative first edition - a jargon-free textbook that provides an introduction to the core issues in social theory. It includes:

- Chapter previews, summaries and a glossary of key terms.

- A ?problem focus? that encourages students to acquire skills of argument and discussion.

- A concluding chapter relating theory to social domains.

- Relevant examples from everyday life to illustrate key theoretical issues.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

A Map of the Terrain: The Organisation of the Book

The Main Story: Key Dualisms in Sociology

This book provides an overview of the major issues in social theory but the organisation of the discussion is unlike that found in most textbooks. Instead of presenting the discussion in the form of a list of issues or authors in social theory, this book is organised around a central theme and problem-focus. This concerns how the encounters of everyday life and individual behaviour influence, and are influenced by, the wider social environment in which we live. The book explores this basic theme in terms of three dualisms which play a key part in sociology; individual–society, agency–structure and macro–micro. These three dualisms are all closely related and may be regarded as different ways of expressing and dealing with the basic theme and problem-focus of the book. The dualisms are not simply analytic distinctions – they refer to different aspects of social life which can also be empirically defined. It is important not to lose sight of this fundamental truth since the sociological problems they pose cannot be solved solely in theoretical terms any more than they can by exclusively empirical means. In this sense, both empirical research and ‘theorising’ must go hand in hand (see Layder, 1993, for an extended argument).

Some authors have suggested that the dualisms that abound in sociology – and there are quite a few others that I have not yet mentioned – express divisions between separate and opposing entities that are locked in a struggle with each other for dominance. These authors object to this because they believe that social life is an interwoven whole in which all elements play a part in an ongoing flux of social activity. Dualism, on this view, is simply a false doctrine that leads to misleading and unhelpful distinctions which do not actually exist in reality.

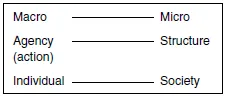

Figure 1.1 Three key dualisms

However, I would side with those theorists who suggest that sociological dualism must not be understood as inherently tied to such a view. The entities referred to in the dualisms must not be thought to be always separate and opposed to each other in some antagonistic manner. Whether or not they are thought of in this way will depend upon which authors or schools of thought we are dealing with. But we must recognise that some authors see dualisms as referring to different aspects of social life which are inextricably interrelated. That is, while possessing their own characteristics, they are interlocked and interdependent features of society. In short, they mutually imply and influence each other. They are not opposed to each other in some kind of struggle for dominance.

In Figure 1.1, the individual–society dualism comes at the base of the diagram with agency–structure above it and macro–micro at the top. This is deliberately arranged to indicate that as we ascend the list we are dealing with more inclusive distinctions. To put this another way, I am saying that the macro–micro distinction comes at the top because it ‘includes’ within its terms some reference to the two underneath. So, by starting with the individual–society distinction I am dealing with the simplest and most basic dualism.

The individual–society distinction is perhaps the oldest and represents a persistent dilemma about the fitting together of individual and collective needs. This is expressed in sociological terms by the problem of how social order is created out of the rather disparate and often anti-social motivations of the many individuals who make up society. As one of the oldest dualisms in sociology, this has been rightly criticised for its tendency to see individuals as if they were completely separated from social influences. This view fails to take into account the fact that many needs and motivations that people experience are shaped by the social environment in which they live (see Chapters 4 and 7). In this sense there is no such thing as society without the individuals who make it up just as there are no individuals existing outside of the influence of society. It has been argued, therefore, that it is better to abandon the individual–society distinction since this simply reaffirms this notion of the isolated individual (or perhaps more absurdly, society without individuals).

Now, there is some merit in the argument against the notion of the pristine individual free from social influences. Some non-sociologists still speak fondly but misguidedly of people as if they stood outside of collective forces. More importantly, some sociologists tend to view the individual’s point of contact with social forces as one which is ‘privatised’ – a straight line of connection between the individual and the social expectations that exert an influence on his or her behaviour (see Chapters 2 and 3). In these cases it is important to view the individual as intrinsically involved with others in both immediate face-to-face situations and in terms of more remote networks of social relationships. In this sense, the individual is never free of social involvements and commitments.

However, as I shall argue throughout, it would be unwise to simply abandon the notion of the individual as ‘someone’ who has a subjective experience of society, and it is useful to distinguish this aspect of social life from the notion of society in its objective guise. To neglect this distinction would be to merge the individual with social forces to such an extent that the idea of unique self-identities would disappear along with the notion of ‘subjective experience’ as a valid category of analysis. This is a striking example of the difference between the cautionary use of dualisms, as against their misuse by the creation of false images. Thus, if the individual is not viewed as separate or isolated from other people or the rest of society, then the individual–society distinction has certain qualified uses. As I have said, one of the drawbacks of speaking of ‘individuals’ as such is that this very notion seems to draw attention away from the fact that people are always involved in social interaction and social relations. This is where the agency–structure dualism has a distinct advantage.

The agency–structure dualism is of more recent origin and derives rather more from sociology itself, although there have been definite philosophical influences, especially concerning the notion of ‘agency’. In Figure 1.1 you will notice that I have put the word ‘action’ in brackets below the word agency. This is meant to indicate that these two words are often used interchangeably by sociologists. In many respects ‘action’ is superior to the word ‘agency’ because it more solidly draws our attention to the socially active nature of human beings. In turn, the fact that people are actively involved in social relationships means that we are more aware of their social interdependencies. The word ‘agency’ points to the idea that people are ‘agents’ in the social world – they are able to do things which affect the social relationships in which they are embedded. People are not simply passive victims of social pressure and circumstances. Thus the notion of activity and its effects on social ties and bonds is closely associated in the terms ‘action’ and ‘agency’.

Another advantage over the individual–society dualism is that action–structure focuses on the mutual influence of social activity and the social contexts in which it takes place. Thus it is concerned with two principal questions: first, the extent to which human beings actively create the social worlds they inhabit through their everyday social encounters. Stated in the form of a question it asks: How does human activity shape the very social circumstances in which it takes place? Secondly, the action–structure issue focuses on the way in which the social context (structures, institutions, cultural resources) moulds and forms social activity. In short, how do the social circumstances in which activity takes place make certain things possible while ruling out other things? In general terms, the action–structure distinction concentrates on the question of how creativity and constraint are related through social activity – how can we explain their coexistence?

Having said this, I have to point out that I am presenting the agency–structure issue in a form which makes most sense in terms of the overall interests and arguments of this book. That is to say, different authors use varying definitions of the two terms and understand the nature of the ties between them in rather different ways. For instance, some authors suggest that agency can be understood to be a feature of various forms of social organisation or collectivity. In this sense we could say that social classes or organisations ‘act’ in various ways – they are collective actors – thus the term ‘agency’ cannot be exclusively reserved for individuals or episodes of face-to-face interaction. In some cases and for some purposes I think it is sensible to talk of the agency of collective actors in this way, but I shall not be primarily concerned with this usage. For present purposes, the most important sense of the term ‘agency’ will refer to the ability of human beings to make a difference in the world (see Giddens, 1984).

Similarly, I am using the notion of structure in the conventional sense of the social relationships which provide the social context or conditions under which people act. On this definition social organisations, institutions and cultural products (like language, knowledge and so on) are the primary referent of the term ‘structure’. These refer to objective features of social life in that they are part of a pre-existing set of social arrangements that people enter into at birth and which typically endure beyond their lifetimes. Of course they also have a subjective component insofar as people enact the social routines that such arrangements imply. In this sense they are bound up with people’s motivations and reasons for action. Although activity (agency) and structure are linked in this way, the primary meaning of structure for this discussion centres on its objective dimension as the social setting and context of behaviour.

There are other meanings of structure, some of which refer to rather different aspects of social life (for example Giddens defines it as ‘rules and resources’), and some refer to primarily subjective or simply small-scale phenomena. I shall not be dealing with these usages in this book but this issue does highlight a difference between the agency–structure and the macro–micro dualisms. That is, whereas agency–structure can in principle refer to both large-scale and small-scale features of social life, the macro–micro distinction deals primarily with a difference in level and scale of analysis. I shall come back to this in a moment but let me just summarise what I mean by the agency–structure dualism. My definitions of these terms follow a fairly conventional distinction between people in face-to-face social interaction as compared with the wider social relations or context in which these activities are embedded. Thus the agency–structure issue focuses on the way in which human beings both create social life at the same time as they are influenced and shaped by existing social arrangements.

There are other differences in usage such as the degree of importance or emphasis that is given to either agency or structure in the theories of various authors and these will emerge as the book progresses. However, the important core of the distinction for present purposes hinges on the link between human activity and its social contexts. By contrast, the macro–micro distinction is rather more concerned with the level and scale of analysis and the research focus. Thus it distinguishes between a primary concentration on the analysis of face-to-face conduct (everyday activities, the routines of social life), as against a primary concentration on the larger scale, more impersonal macro phenomena like institutions and the distribution of power and resources. As with agency–structure, the macro–micro distinction is a matter of analytic emphasis, since both macro and micro features are intertwined and depend on each other. However, macro and micro refer to definite levels of social reality which have rather different properties – for example, micro phenomena deal with more intimate and detailed aspects of face-to-face conduct, while macro phenomena deal with more impersonal and large-scale phenomena.

There are considerable overlaps between structures and macro phenomena, although there are important differences in emphasis. Macro phenomena tend to deal with the distribution of groups of people or resources in society as a whole, for example, the concentration of women or certain ethnic groups in particular kinds of jobs and industries, or the unequal distribution of wealth and property in terms of class and other social divisions. However, macro analyses may include structural phenomena like organisational power, or cultural resources such as language and artistic and musical forms, which may have rather more local significance. The common element in both structures and macro phenomena is that they refer to reproduced patterns of power and social organisation. There is also some overlapping between micro analysis and the concern with agency and creativity and constraint in social activity. The main difference is that micro refers primarily to a level of analysis and research focus, whereas a concern with agency focuses on the tie between activity and its social contexts.

I think we can see from these brief preliminary definitions, that not only is the individual–society problem closely related to the agency (action)–structure issue, but that both are directly implicated in the macro–micro dualism. That is, if micro analysis is concerned with face-to-face conduct, then it overlaps with self-identity and subjective experience as well as the idea that people are social agents who can fashion and remake their social circumstances. Similarly, if macro analysis concentrates on more remote, general and patterned features of society, then it also overlaps with the notion of ‘social structure’ as the regular and patterned practices (institutional and otherwise) which form the social context of behaviour. So, my point is that these different dualisms overlap with each other and that the macro–micro dualism includes elements of the other two. This is the reason that it is the principal focus of this book, although I shall have something to say about them all throughout.

As I have tried to make clear, these are not distinctions without substance. They all mean something quite definite even though they overlap to some extent. They all refer to divisions between different sorts of things in the social world, and it is important to remember that these may be complementary rather than antagonistic to each other. As mentioned earlier, some sociologists object to the influence which these sorts of dualism have had on sociological thinking, and this is something we shall go on to consider. However, the whole point of presenting them and being clear about what they mean right from the start is that it is the only way of evaluating the arguments both for and against this point of view. We can only really understand why some sociologists have objected to them, and judge whether their arguments are sound, if we know what it is they are objecting to.

Apart from these three key dualisms there are a number of others that have played an important role in social analysis such as ‘objectivism–subjectivism’, ‘dynamics–statics’, ‘materialism–idealism’, ‘rationalism–empiricism’. I shall not be discussing these here, I simply wish to indicate that they are fairly widespread and ingrained in routine social analysis. It is important to be aware of this because it is part of the context against which the ‘rejectors’ of dualism are protesting. Also, since this book is organised around the theme of the macro–micro dualism, it is important to have some sense of the wider context of dualistic thinking in the social sciences.

The Organisation of the Book

Let me now turn to the way in which the book is organised from Chapter 2 to 12. One of the main themes which group certain writers and schools of thought together is based on the extent to which they reject or affirm dualism in social theory, especially those of agency–structure and macro–micro. With regard to this basic organising principle we can see that the book is divided into four parts. Each part deals with approaches to theory which either affirm or reject these dualisms in different ways.

In Part 1, I examine the work of Talcott Parsons (Chapter 2) and the variety of theoretical work that has stemmed from the writings of Karl Marx (Chapter 3). It is often thought that the work of these authors is diametrically opposed and, to a large extent, this is true. However, there are common features in their work which become more apparent as we compare them with other approaches. One of these common featur...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Preface to the First Edition

- 1 A Map of the Terrain: The Organisation of the Book

- PART 1 THE VIEW FROM ON HIGH

- PART 2 WHERE THE ACTION IS

- PART 3 BREAKING FREE AND BURNING BRIDGES

- PART 4 ONLY CONNECT: FORGING LINKS

- Glossary

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Social Theory by Derek Layder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.