![]()

1

What is movement?

Everything that we discover about life, we discover through movement. Light waves reach the eye, sound waves contact the ear. Both smell and taste involve movement. Above all, our capacity to touch and move to gain further experience, confirms our awareness.

(Hodgson 2001: 172)

This chapter provides a theoretical framework which serves as a reference point, or identity kit, for the many examples of children’s activities which illustrate subsequent chapters of this book. It also provides a way of thinking about, supporting, enriching and recording children’s movement for all those concerned with early childhood education.

The indivisibility of movement from human functioning may be one of the reasons why its importance in terms of child development is not always given the serious recognition it deserves. It is so inbuilt that it is not until movement is seen to be dysfunctional or ineffective in some way, such as in autism, depression, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, cerebral palsy or mood swings, that it emerges as a significant educational phenomenon. Postgraduate Dance Movement Therapy programmes on offer in the UK and elsewhere include diagnostic and treatment tools in their training and, increasingly, dance and movement join art, drama and music therapies in their bid to modify and enhance living. In the therapeutic context non-verbal communication of the body is ‘incorporated with other research to refine coping distinctions and measure changes’ and, as such, is universally acknowledged. (Bartenieff 1980: viii)

While welcoming such advancements in the therapeutic field, I believe that movement plays an equally important role in the growth, development and education of all children. However, because movement of young children is seen to be a part and parcel of their everyday lives the danger is that it can be taken for granted and overlooked in terms of its importance in the educational spectrum. Those concerned with child care and education may see no reason to classify and analyse something which seems so obvious. In contrast, however, as soon as children show the first signs of emergent reading skills, help is at hand; resources, methods and procedures are actively sought and discussion within and between family units abounds. Similarly, as children’s interests in numeracy become apparent, parents are the first to join in the bigger/smaller, taller/shorter phase of discrimination. Even if parents and early childhood practitioners do not have detailed knowledge in these areas, realising its importance they seek it out and provide materials and experiences which assist learning at this stage.

In movement, too, important achievements are noted, valued and discussed with pride. Photograph albums and family CD libraries are filled with illustrations documenting such events as early, unsteady steps, digging in the sand, kicking a ball and swimming without support. But there the similarity ends. Although there is often movement-oriented provision in parks, playgrounds and gardens, detailed guidance for promoting, observing and recognising activities stimulating growth, development and creativity is far behind that in other areas of learning. Sometimes adults ‘sense’ what is needed to help children initiate, consolidate or progress in their movement activities but, however valuable and successful this sensing may sometimes seem to be, it needs to be related to a much larger canvas of knowledge. If parents and early years practitioners are to function knowingly it is necessary to extend beyond sensing. If they are to take responsibility for movement as an important area of children’s experience then they need to know what ‘constitutes’ movement just as they need to know about all the other areas of learning for which they make provision.

The challenge was to find a model which was sufficiently proven and sufficiently flexible to relate to young children in a variety of situations: a model or framework which would establish general principles and cater not simply for provision but also for extended learning in objective and creative contexts. In choosing the framework used throughout this book acknowledgement is made to the theories of Rudolf Laban (1948, 1966, 1980) and those concerned with the development of his ideas including Bartenieff (1980), Lamb (1965), North (1972), Preston (1963), Preston-Dunlop (1998), Redfern (1973), Russell (1965) and Ullmann who continued his work after his death. After a remarkable life spent in researching movement in a variety of theoretical and practical contexts Laban’s findings remain the most pertinent and relevant available today. As Hodgson (2001: 55) writes:

A good deal of Laban’s work and theory forms the foundation of so much of our understanding of movement, that quite often people come to regard it now as common belief.

This allegiance may be partly due to his guiding principles which echo those of leading educational theorists of today, and which permeate my own thinking. Laban did not create a ‘one and only’ model but instead inspired others to take up and develop his principles in the variety of fields in which he worked. Preston-Dunlop (1998: cover), Laban scholar and researcher, writes:

His ideas have innovations not just in dance, but also in acting and performance, in the study of non verbal communication, in ergonomics, in educational theory and child development, in personality assessment and psychotherapy.

In her conclusion she comments (ibid.: 269):

Today his [Laban’s] concepts are alive and well, adapted, pruned and developed to accommodate the needs and demands of the twenty-first century.

Theoretical framework of movement

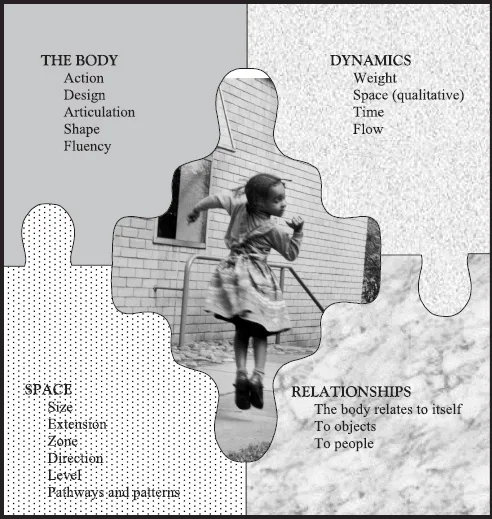

Human movement is not only unique to the species but is also unique to each individual within it. To understand and recognise the complexity of individual uniqueness it is necessary first to establish the common denominators from which personal movement springs. The body, the instrument of action, is central to the classification of movement. Giving colour and form to the ‘playing’ of that instrument are three important and interrelated categories:

- dynamics which relates to how the instrument moves

- space which refers to ways in which the body inhabits and uses space

- relationships which identifies ways in which the body acts and interacts with people and objects.

THE INTEGRATION OF MOVEMENT

Figure 1 A general classification of movement in relation to young children from 0 to 8 years

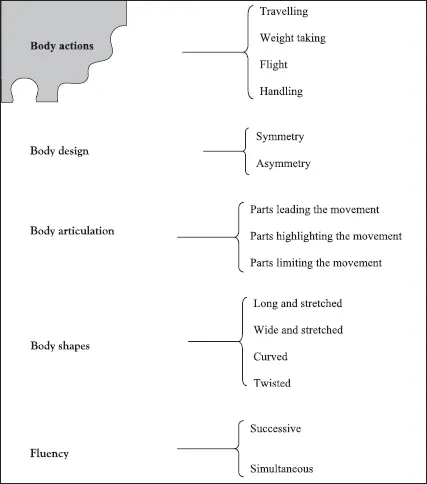

The body: what takes place

Figure 2 The body: the instrument of movement activity

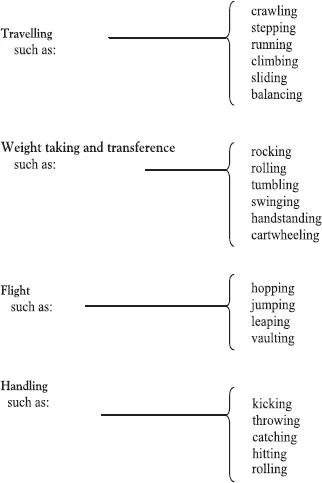

The body in action

The body moving into action is a vital part of all movement activity whether it is spontaneous or in response to structured situations at home, in the play centre, in the supermarket, in the early years setting or at school. It is through the dynamic and spatial use of a growing number of separate and related actions, action schemas, that children become increasingly competent and versatile in a variety of movement situations.

Figure 3 The body in action

At first actions of babies are restricted to the relatively confined spaces they inhabit and the people with whom they are in contact. Reaching, grasping, sucking, wriggling and kicking feature dominantly in the early months. As soon as they become more independently mobile they are able to invest their actions in spatial areas previously unavailable to them. The shuffling and crawling activities of babies develop into a range of travelling actions which typify the play of young children as they transport themselves from one place to another.

Sometimes children enjoy staying put in small pockets of space and explore actions which support or transfer their weight; they rock, roll over, turn upside down and, in all these activities, face different perspectives of their world. As they amass and develop a more complex range of action schemas so their perspective experience widens. The Curriculum Guidance for the Foundation Stage draws attention to the importance for children to see things from different perspectives such as from the top of a climbing frame, in a tunnel or below a box (QCA 2000: 102).

Actions associated with dexterity, involving handling objects, such as throwing, kicking and catching which feature in young children’s ‘games play’, also have their early roots. The baby’s grip and release of a rattle through to the sophisticated throwing and catching of the eight-year-olds represent another category of important body actions children gradually add to their repertoire.

Overcoming gravity and being in flight is a delight for all children and is something which remains with them throughout the first phase of living and beyond. Before they can manage to push off and make themselves airborne they jump from a stair, kerbstone or chair which, in reality, means dropping down rather than jumping down. Although at this stage they are not yet quite there, nevertheless the children are getting the feel of the activity. Being helped to jump by or with adults...