![]()

1 | Research Traditions in Education |

OVERVIEW

This chapter introduces some of the key concepts used in the book by introducing you to some of the more important broad traditions of education research. This leads you into an introduction to the practitioner research movement, which underpins the ideas that form the core of this book.

Introduction

Let us assume that you have identified some aspect of your professional practice in your classroom that is puzzling you. You may have noticed that one particular technique you use to encourage effective learning does not appear to be working as well as it used to, or that another is working very effectively. You may have seen something in the news or read something in the educational press that reminded you of your own classroom or at least caused you to wonder how it might apply to your own professional situation. At this point you have taken the first step as a researcher in that you have identified an educational issue that might need resolving. We could generalise by saying that much educational research focuses on interesting puzzles that have been identified by practitioners.

The second step in the process is to carry out a small-scale study of the aspect of your professional practice in the classroom that is puzzling you. However, as a beginning researcher in education you may not realise that there are a number of research traditions in education and that you may find yourself operating within them without realising that you are doing so. It is important that you recognise the tradition you are perhaps unknowingly accepting, as each has various methodological advantages and disadvantages which feed through to your findings and conclusions. In fact, the practitioner research approach we have described above is itself just one tradition amongst many. These traditions are themselves worthy of research, as they hide puzzles that have a knock-on effect to the research they generate in ways that we will discuss in this chapter.

Two crude traditions

One of the most common ways of identifying traditions of educational research is to identify a distinction between quantitative and qualitative approaches to research. As the term suggests, quantitative educational research deals with measurement of quantities of some sort or another. If you studied for your teacher’s qualification in the UK before the 1980s it is likely that at some point you will have been introduced to the so-called disciplines of education, in particular the psychology and sociology of education. There are still parts of the world where such an approach to preparing students for teaching flourish. Research within the psychology of education set out to make the understanding and improvement of education scientific, in that it would provide objective knowledge about education so as to allow for that knowledge to be used to improve the learning of pupils and the teaching techniques of teachers. Similarly, early forms of the sociology of education made extensive use of statistical analyses with, for example, pupil achievement being measured in quantitative terms.

There have been a number of criticisms of this approach to educational research, not least being the fact that education involves interpersonal relationships whose subtleties cannot easily be captured in quantitative terms. The argument being presented by such critics is that education involves issues to do with the quality and nature of these relationships, so educational research is uniquely qualitative. As such, objective scientific measurement of the activity is more often than not inappropriate as a quantitative approach to qualitative debates can rarely capture such inquiries, though they may be used to inform aspects of them.

Two more subtle traditions

In outlining the quantitative approach to education research we have referred to research being scientific and therefore producing objective knowledge. That conception of science is itself a particular tradition with a particular understanding of the nature of knowledge and one we now need to examine in more detail.

THE POSITIVIST, COMMONSENSE TRADITION

This is an approach to knowledge which is usually first referenced to August Comte’s 1844 publication, Discourse on the Positivist Spirit. He argued that there were three broad ways in which natural phenomena can be explained, the theological, the metaphysical and, finally, the positivist, this last being an approach whereby natural events are properly to be explained by reference to empirically observable concrete phenomena. From that conception of how knowledge is to be gained comes what might be called the commonsense view of science.

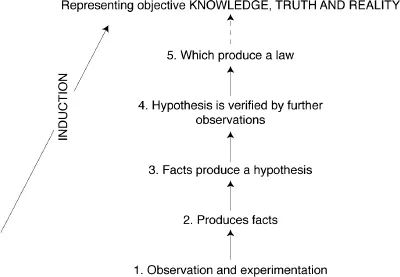

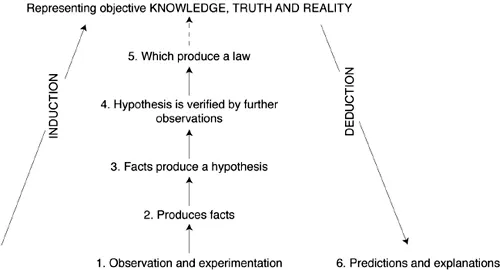

This views scientific research as progressing through a series of steps as follows. The researcher begins with observations and experiments which produce facts which in turn allow a hypothesis to be developed. The hypothesis is further tested so that it can be confirmed and, once it has been confirmed, this allows the researcher to produce (or induce via a process termed induction, where one moves from some to all) a law which represents objective Knowledge,1 Truth or Reality. This aspect of the research tradition is represented in the five steps presented in Figure 1.1. The final stage in this research tradition is to use the objective Knowledge that has been produced through the empirical process represented in Figure 1.1 to produce explanations and predictions based on that Knowledge by a process termed ‘deduction’ (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1: THE FIVE STEPS OF TRADITIONAL RESEARCH

Figure 1.2: THE SIXTH STEP OF TRADITIONAL RESEARCH

Illustration: the positivist tradition of research

If you decide to carry out an inquiry which has the following features:

- you identify a hypothesis;

- you use observations to prove your hypothesis;

- you make use of the facts identified by your proof to identify some sort of objective Knowledge; and

- you deduce a universally applicable conclusion

then you are clearly operating within a positivist tradition of research, irrespective of whether your work is to be seen as quantitative or qualitative research (or even a mixture of these two approaches).

An example drawn from the English context shows how this tradition might be relied upon to justify practice. Let us assume that after a number of observations of young children successfully learning to read in, say, Singapore, it has been suggested that it is necessary to have highly structured reading hours provided on a daily basis, with equally rigidly structured activities to follow. This hypothesis to explain why it is that Singaporean children read so effectively is then tested by observing as many young Singaporean children’s reading lessons as possible, to produce the law that all young children can be taught to read effectively in this way. Given this empirically derived Knowledge it is then but a small matter to deduce the prediction that the reading abilities of young English children will be improved by using these methods. In this way an apparently sound, evidence-based policy decision can then be introduced to the teaching profession.

This tradition has at least three major problems which you need to be aware of, as they will seriously compromise your findings if you do not find ways of addressing them.

Problem 1

The first step in this tradition depends upon observation. But observation itself depends upon what we are interested in observing. That is, we do not approach situations, especially social situations such as those we find in the classroom, free of certain assumptions about their nature. These assumptions allow us to select from the wealth of information that we are presented with only those details that interest us, so we are not observing in some pure, assumption-free manner. Consequently, the kinds of knowledge that we create as we observe social situations are inevitably influenced by the assumptions we bring to bear on the situations we observe and try to make sense of.

Problem 2

Figure 1.1 shows clearly that induction, the move from some to all, underpins the move from singular observations to universally applicable objective Knowledge. Yet the number of observations that are required to justify the move from some to all, from the finite to the infinite, would have to be an infinite number too. As finite creatures ourselves this is clearly impossible. The critical effect of this basic problem on positivism has been described thus: ‘That the whole of science … should rest on foundations whose validity it is impossible to demonstrate has been found to be uniquely embarrassing’ (Magee, 1973: 21).

Problem 3

Figure 1.2 indicates that deduction, the move from all to some, underpins the move from universally applicable objective Knowledge to the singular application of that Knowledge. The difficulty here is that the crucial distinction between something being true and an argument being valid is being blurred. Here are two examples of logically valid arguments, valid in that they move from ‘all to one’ in a logically valid way:

A

- All books on research methods are boring.

- This is a book on research methods.

- Therefore this book is boring.

B

- All writers on research are female.

- The author of this chapter is a writer on research.

- Therefore the author of this chapter (Peter Gilroy) is female.

Step 1 of both arguments are assumptions but only argument B’s assumption is demonstrably false. However, that does not prevent argument B’s conclusion being valid but untrue. The point here is that even if there were to be universally applicable Knowledge about the social world you have to take very great care in relating it to particular situations, as deduction alone will not guarantee the truth of your conclusions.

We said that you would need to address these three problems if you wanted to work within this positivist tradition. If you do not then you might produce conclusions to your research that assumed that the observations you made were untainted by the assumptions you bring to bear to select one set of observations from another. This would have the problem of preventing you seeing that your conclusions were inextricably linked to the assumptions that underpinned the observations you selected as significant. The second problem we have identified makes it clear that you cannot justifiably make a universal generalisation from specific observations, which would clearly influence the way you treated your findings. The third problem suggests that the move from all to some, the reverse of the problem of induction, is one that might be valid but you would still need to test for its truth, irrespective of its validity.

These three problems seem to lead towards a modification of positivism which is so drastic that it in effect represents a rejection of the tradition. The key modification is to reject the attempt to produce universal conclusions and to accept the need to operate at a more specific level of inquiry. We identify this tradition as contextualism, and will now examine its key features.

THE CONTEXTUALIST TRADITION

There are a number of different approaches to educational research that could be accommodated within this broad tradition, but before identifying them we first need to establish the key features of the tradition itself. The central identifying feature of the tradition is its emphasis on context as providing the background to any social inquiry, none more so than educational inquiry.

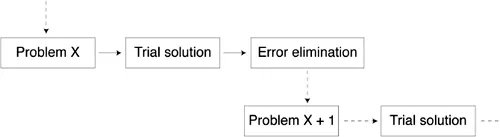

A key thinker in this area is Karl Popper, who claimed to have solved the problem of induction ‘in 1927, or thereabouts’ (1971: 1). He accepted that it is not possible to justify universal Knowledge by reference to finite observations but, rather, that instead we have to falsify them by testing them to destruction. In addition he accepted that observations are dependent upon the various assumptions made by the person carrying out the observation or, as he put it: ‘Observation is always selective … these observations … presupposed the adoption of a frame of reference … a frame of theories’ (1974: 46–7). He argued that inquiry is caused by recognising that a trial solution that had been offered up for falsification (or error elimination) would eventually produce a further problem that would require error elimination and so on, with the process of inquiry being never ending. Consequently the knowledge that is created is provisional, always the possible object of further attempts to falsify it. This approach is represented in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: THE PROCESS OF INQUIRY

It is Popper’s notion of a frame of reference that we term context an...