![]()

| 1 | Learning To Writen |

| | Debra Myhill |

Introduction

Learning to write is one of the most challenging endeavours we offer a young child. We learn to talk naturally and effortlessly through our interactions with others and no child, other than one with specific learning difficulties, does not learn to talk. But learning to write is a taught process and we only learn to write the full repertoire of conventions of our language if we are taught to write, whether that be the demands of shaping letters and spacing words or the demands of conveying meaning through written language. Kress (1994) reminds us that writing is more difficult than reading, because reading is a process of making meaning from text, whereas writing is a process of encoding meaning through text: reading is a receptive process, whereas writing is a productive process. Kellogg (2008) argues that writing is one of the most difficult and demanding intellectual tasks we engage in, and he suggests that it is as intellectually effortful as playing chess. So it is no surprise that children sometimes struggle with writing.

But at the same time, writing is everywhere. In terms of learning to write, it is impossible to separate children’s world experiences of reading text from their attempts at writing. As novice writers, they don’t enter the writing classroom with no knowledge – they bring a wide understanding of how texts are shaped: understanding of labelling and design on sweet packets; knowing about directions and signposting; being able to discriminate between adverts and stories; knowing the social function of thank you letters, shopping lists, and name labels on property.… These are the foundations upon which learning to write is built. And in the twenty-first-century world of digital natives, young children’s experiences of writing are likely to include electronic written forms – emails, text messages, eBay adverts, web pages. Indeed, it would be very easy to argue that, as technology has flourished and children are growing up comfortable with the affordances of technology, young people write more than ever. Certainly, communication that was once oral such as a phone call is increasingly being replaced by texting or emailing, and the accessibility of the internet creates new spaces and provides ease of publishing writing through blogs or wikis, for example. Being able to communicate effectively through writing remains an essential skill for children to learn, not simply because of the role it plays in academic development and assessment, but because of its significance in social development and social networking.

So what can recent research tell us about how children learn to write?

The writing process

Perhaps surprisingly, research in writing is a young and relatively immature field of research, particularly compared with the extensive and well-developed body of research on learning to read. This is particularly true in cognitive psychology where the research has really only developed in the past 30 years or so. But this research has advanced our understanding of the process of writing and of the kinds of demands that writing makes upon our cognitive resources, our ‘brain power’, you could say.

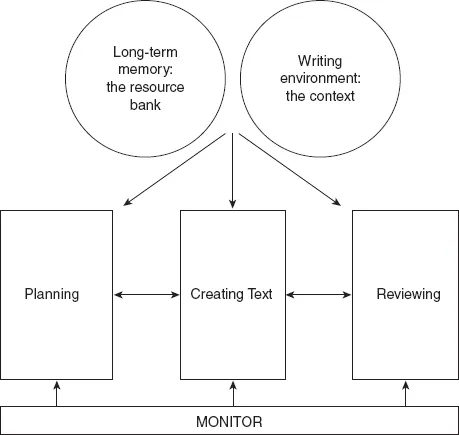

In the early 1980s, Hayes and Flower (1980) first proposed a model of writing. This was an attempt to explain the mental processes that are involved in moving from ideas in the head to a completed written text on the page or screen. They saw writing as drawing on three important and inter-related components:

- the writing environment: this covers everything ‘outside the writer’s skin that influences the performance of the task’ (Hayes and Flower, 1980: 12). So this includes the nature and purpose of the writing task, the writer’s motivation to write, and whether it is individual or collaborative writing. You could think of this as the context for writing.

- the writer’s long-term memory: long-term memory is the permanent store of knowledge and experience that we all draw on when we write. This includes our knowledge of texts and text types, our knowledge about writing, and our linguistic knowledge of words and syntax. You could think of this as the principal resource bank for writing.

- the writing process: this addresses the activities that occur in the period of writing, from the stage of starting to write to the completion of the piece of writing.

Hayes and Flower suggested that the writing process was essentially composed of three different kinds of writing activity. Generating ideas for the writing and working out how you are going to approach the writing task is a Planning activity. This might include writing a formal plan but equally it is also simply the thinking and mental planning that often occurs before we attempt to set words on the page. The activity of producing written text, of transforming thoughts or spoken ideas into written language is a Creating Text activity. Hayes and Flower called this activity ‘translating’ but this is perhaps not such a helpful term because of its association with translating from one language to another, and because it suggests that getting words on the page is a simple linear act of translating thoughts into words. Reading through the text and amending it is a Reviewing activity. This may sound vaguely familiar as the National Curriculum talks of writing in terms of Plan – Draft – Revise – Edit. But these are chronological – first you plan, then you draft, etc. However, Hayes and Flower emphasise that planning, writing and reviewing are not simple chronological stages, but they inter-relate and overlap, and that effective writers repeatedly switch between these activities. They argue that we have a monitor, a kind of mental manager, which switches our attention as we are engaged in writing from one activity to another. So as I am creating this text now I am engaged in a Creating Text activity, but I repeatedly stop, sometimes several times a minute, to re-read what I have written. This is a Reviewing activity. And sometimes as I am Creating Text or Reviewing, I think of another point I want to make and I note it down in my plan (I do have a written plan for this!) – this is a Planning activity.

All of this mental activity is influenced by the resources available in the long-term memory and by the writing environment. Many of the pauses while we are Creating Text are while we try to find the right word, searching through the long-term memory for the one that will fit the bill perfectly. Sometimes, pauses during writing are to review whether the developing text matches the task set – for example, does it look like a letter? Is the style of writing appropriate for a letter? And, of course, if you hate writing letters anyway, your motivation to pay attention to your writing may be less than ideal!

For a graphic overview of Hayes and Flower’s model see Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 A simplified overview of Hayes and Flower’s (1980) Model of Writing

But one major problem in Hayes and Flower’s model is that it describes writing in proficient writers, writers who no longer need to devote much attention to shaping letters, spelling or punctuation and who approach each new task of writing with a wealth of writing experience behind them. As Berninger et al. (1996) point out, there are significant differences between mature writers and developing writers: ‘in skilled writers, planning, translating and revising are mature processes that interact with one another. In beginning and developing writers, each of these processes is still developing and each process is on its own trajectory, developing at its own rate’ (1996: 198). We are interested here in early years writers for whom just getting a word onto a page can be a major endeavour.

Creating text: the challenges of orthography and transcription

As any teacher of writing in an early years classroom will know, one of the most significant challenges facing a novice writer is mastering both the physical and the symbolic aspects of writing. Handwriting is a perceptual-motoric skill: in other words, it demands an interplay between fine motor skills and visual perception and evaluation. Learning to control a pencil so that you can shape letters accurately and become a fluent handwriter is a prerequisite skill for developing as a writer. Indeed, recent research (Connelly and Hurst, 2001) has found a direct link between writing fluency and writing quality – children who can write fluently at a good speed tend to write more effective texts. Helping young children to become more fluent writers also supports the activity of creating text (Berninger et al., 2002). There is also evidence (Tucha et al., 2007) that placing too much emphasis upon neatness is a barrier to the development of fluency needed to facilitate growth as a writer. It will probably be no surprise to discover that girls tend to write faster and more fluently than boys (Barnett et al., 2009), though this should not be taken as a deterministic deficit model of boys as writers; boys are not unavoidably worse at handwriting than girls. Undoubtedly, a key goal of the teaching of handwriting is to secure fluency and legibility as automated processes, so that the writer is not devoting precious thinking attention to the transcription of text but can instead think more about what they are writing.

Alongside mastering the physical mark-making process of handwriting, young writers are simultaneously learning about the orthographic conventions of written language. Orthography is the way a language represents spoken words in written symbols: the conventions of sound–symbol correspondence and text layout. Research shows that young children’s earliest spontaneous writings take the form of scriptio continua, strings of letters with no word spaces between them (Ferreiro and Teberosky, 1982). However, children’s early mark-making soon shows their sensitivity to the literate world around them and they often produce word-like letter strings. Tolchinsky and Cintas (2001) investigated how early years writers develop understanding of words and word spacing and show that recognising word boundaries is no simple task. Early writers often joined words together or left gaps where there should be none. Our experience as talkers does not help us to understand word boundaries as the word is not as visible in talk as it has to be in writing. I remember as a small child being taught orally the French word for window by my father, and several years later when I started to learn written French at school being very surprised to discover that the word for ‘window’ was not lafenêtre but la fenêtre. Young writers have to learn about words as graphemic units, and in English this is not always logical (why football but high chair?). In the early stages of writing development, lexical and non-lexical items are often amalgamated – for example, mydog – the lexical item with its attached grammatical words becomes a unit. This is, of course, exactly what I did as a child learning how to say ‘window’ in French – I heard the determiner la and the noun fenêtre as a single word unit. In the Talk to Text project, one noticeable facet of classroom writing was the children’s own emphasis on finger-spacing and their reminders to each other to use their fingers to create the spaces between words. These children had learned about the significance of word boundaries.

Too much to do: cognitive overload and working memory

For all of us, child or adult, our working memory (or short-term memory) is critical to our capacity to deal with tasks. In essence, our working memory is that part of the brain which temporarily stores information and allows us to manipulate information to complete a given task (Baddeley and Hitch, 1974). It has limited capacity so if we ask too much of it, we cannot successfully complete the task. Most of us would be able to remember a single telephone number long enough to write it down, but we would struggle to remember two telephone numbers. And the experience that will be familiar to many, of asking for directions and then not being able to recall them all is an example of the limited capacity of our working memory. These, however, are all examples of straightforward retention of information and our ability to recall it. But working memory also deals with manipulating information and if we ask too much of it, it cannot cope: most of us could multiply 2 × 18 in our heads; far fewer of us could multiply 183 × 24 because our working memory cannot manage to hold the information required long enough to perform the calculation.

This is called cognitive overload by psychologists and it is particularly relevant to writing because writing is a task which makes heavy demands on our working memory. Young children typically have very small working memory capacities that increase gradually until the teenage years, when adult levels are reached – approximately two to three times greater than that of 4-year-old children (Gathercole et al., 2004). Having to pay attention to handwriting, word spacing and spelling means that young writers have little or no working memory available to think about other aspects of writing, such as what they want to say and how they might say it. Typically, a writer who has progressed beyond scriptio continua but is still in the earliest stages of creating text is likely to be concentrating so hard on the letters that make up a word that he or she may not be able to hold a whole sentence in his/her head. McCutcheon (2006: 120) explains that in young children the process of transcription and the process of text generation ‘compete for cognitive resources’. This is why it helps writers when they achieve fluent handwriting and when they can spell and punctuate reasonably confidently. It is also why in the Talk to Text project we looked at the ways in which talk might be a tool for reducing cognitive load and releasing working memory capacity to attend to higher-level aspects of writing.

Communities of writers: writing as a social practice

When children learn to write, they are not simply learning to master a symbolic system, they are learning about the social practices that writing embodies. They learn not just to ‘do writing’, but what writing can do. Learning to write is not simply about learning how to generate written text; it is about learning how to create meaning through text. Some researchers suggest that the urge to make marks on a surface is as instinctive and ‘hard-wired’ as babbling before learning to reproduce meaningful words and sounds in speech. One study (Gibson and Levin, 1980) demonstrated that if children were given a surface to write on and two tools, only one of which made a mark (e.g. a marker pen and a plastic stick), children rejected the non-marking tool and played with the tool that left a mark. They believed that it was the marks themselves that motivated the children to use the tool that left marks, and that children invested the marks with meaning. It is certainly true that ‘if children are provided with marking tools, a suitable surface on which to write, and a safe place to play, they begin to make marks at quite an early age’ (Schickendanz and Casbergue, 2004:) and that ‘scribbling’ is an important aspect of learning to write. Through their early mark-making, children develop some of the hand–eye co-ordination needed for writing, and eventually learn how to discriminate between writing and drawing. Crucially, they also learn that marks can have mean...