eBook - ePub

Health, Behaviour and Society: Clinical Medicine in Context

This is a test

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Health, Behaviour and Society: Clinical Medicine in Context

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

There is more to a person than a particular symptom or disease: patients are individuals but they are not isolated, they are part of a family, a community, an environment, and all these factors can affect in many different ways how they manage health and illness. This book provides an introduction to population, sociological and psychological influences on health and delivery of healthcare in the UK and will equip today's medical students with the knowledge required to be properly prepared for clinical practice in accordance with the outcomes of Tomorrow's Doctors.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Health, Behaviour and Society: Clinical Medicine in Context by Jennifer Cleland, Philip Cotton, Jennifer Cleland,Philip Cotton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Doctor as a Scholar and a Scientist

chapter 1

An Introduction to Health and Illness in Society

Achieving your medical degree

This chapter will help you to meet the following requirements of Tomorrow’s Doctors (2009).

9 Apply psychological principles, method and knowledge to medical practice.

(a) Explain normal human behaviour at an individual level.

(b) Discuss psychological concepts of health, illness and disease.

(a) Explain normal human behaviour at an individual level.

(b) Discuss psychological concepts of health, illness and disease.

10 Apply social science principles, method and knowledge to medical practice.

(a) Explain normal human behaviour at a societal level.

(b) Discuss sociological concepts of health, illness and disease.

(a) Explain normal human behaviour at a societal level.

(b) Discuss sociological concepts of health, illness and disease.

11 Apply to medical practice the principles, method and knowledge of population health and the improvement of health and healthcare.

(b) Assess how health behaviours and outcomes are affected by the diversity of the patient population.

(b) Assess how health behaviours and outcomes are affected by the diversity of the patient population.

It will also introduce you to academic standards as set out in other documents such as the joint GMC and MSC guidance called Medical Students: Professional Values and Fitness to Practise (www.gmc-uk.org/education/undergraduate/professional_behaviour.asp) and the core curriculum for The Scottish Doctor (www.scottishdoctor.org) as published by Scottish Deans’ Medical Curriculum Group.

Chapter overview

After reading this chapter, you will be able to discuss the following:

- What is normal?

- What is normal in terms of health?

- the medical model

- the social model

- Influences on health

- individual

- environmental and occupational

- political and social

- WHO definition of health

What is normal?

Different people use the word ‘normal’ in different ways. A philosopher views the normal as the most usual. Psychologists and statisticians refer to normal as the middle range of a distribution of values (i.e. statistically normal). A sociologist defines ‘normal’ as that which is in line with a rule for a particular social or cultural group in society. The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘normal’ as ‘conforming to a standard’. In medicine, ‘normal’ is often used to mean an absence of physiological pathology (Offer and Sabshin, 1991). In common speech, ‘normal’ may simply mean ‘not abnormal, not strange’!

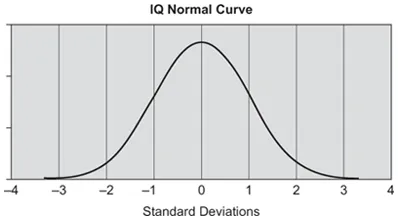

You will come across ‘normal’ being used in lots of different ways in medicine. In terms of statistical probability, the mathematical concept of normal distribution means most things being measured are within one standard deviation (the spread of values) in either direction from the mean (the population average or central point). Usually this is taken as ‘normal’, and is the basis of many measurements commonly used in medicine such as height and weight for age in childhood, IQ (see Figure 1.1), distribution of blood pressure and so on. However, bearing in mind the sociological perspective, measurements of what is normal usually need to be interpreted with reference to group norms. For example, for an adult, a normal resting heart rate ranges from 60 to 100 beats per minute (bpm). For a well-trained athlete, however, a normal resting heart rate may be as low as 40 to 60 bpm. Heart rate is also influenced by age: 120–160 bpm is normal for babies.

Figure 1.1 IQ distribution.

Source: IQ Comparison Site www.iqcomparisonsite.com. Copyright © 2007 Rodrigo de la Jara. Reproduced with permission.

In terms of conforming to a standard, what is considered acceptable behaviour in one population, or social group, may not be seen as such in another group. Dress codes, work habits, gender stereotypes and social intercourse are quite strictly defined in the various cultures of the world and deviation is not generally well accepted. At present homosexuality is seen by most as a normal variation in sexual orientation and sanctioned by law in the UK, for example same-sex civil marriages became legal in 2005. But, in May 2010 in Malawi, a gay couple were arrested the day after their engagement party and jailed for 14 years’ hard labour under the country’s anti-gay legislation. This example illustrates starkly how different cultural groups have different norms. Figure 1.2 shows a picture of a woman from the Kayan tribe in Thailand where the use of brass rings to elongate the neck (by downward displacement of the collar bones and upper ribs) is thought to enhance beauty. However, she would likely be thought abnormal if seen in a UK city centre.

Figure 1.2 Kayan brass rings.

Source: A Kayan woman refugee in Thailand shows her neck rings to sightseers. Author: Steve Evans www.flickr.com/photos/babasteve/351227116 licensed under Creative Commons.

As a further thought on normality, consider this true experience of a final year medical student. As he travelled by train to an Indian village for his student elective, he thought how abnormal everything was, the people, their culture, the climate and so on. As his journey progressed, he was suddenly struck by the thought, ‘It’s not all that I’m seeing which is abnormal, it’s me. I am the one with the different appearance and different cultural background’. Few people regard themselves as abnormal, yet everyone is abnormal to somebody!

What is ‘normal’ in terms of illness and health? An introduction to the medical and social models of health and illness

There is also a pathological or physiological concept of normality. This ‘medical model’ defines health as essentially the absence of disease. Using this concept, to ‘cure’ means to restore a function or organism to a healthy (normal) state or to eradicate illness (abnormality) through diagnosis and effective treatment.

The medical model is driven by the belief that medical science should find cures for diseases in order to return people to health. This model was developed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and was associated with the discovery of the mechanisms that lay behind infections – specific causes were linked to specific diseases in particular organs, and the task of the physician was to trace the presenting symptoms back to their underlying origins. The era of modern medicine began with the discovery of the smallpox vaccine at the end of the eighteenth century, discoveries around 1880 of the transmission of disease by bacteria, and then the discovery of antibiotics (the sulfa drugs) around 1900.

The medical model emphasises the need to have a good knowledge of biochemistry, pathology, physiology and anatomy in order to diagnose disease. It proposes a scientific process involving observation, description and differentiation, which moves from recognising and treating symptoms to identifying disease aetiologies and developing specific treatments. As such, evidence has always been at the core of the medical model.

With the medical model, informed by the best available evidence, doctors advise on, coordinate or deliver interventions for health improvement (Shah and Mountain, 2007). It is now considered unacceptable to determine treatment on the basis of instinct or ‘gut feeling’. Western practice is also increasingly determined by evidence-based guidelines and protocols, with legal consequences for non-compliance.

Development of the medical model enabled biological explanations and treatments for diseases to replace practices based on religious and cultural tradition (e.g. the Greek ‘four humors’), which in turn helped to reduce fear, superstition and stigma, and to increase understanding, hope and humane methods of treatment (Tallis, 2004). This was a huge progression. However, the medical model, and its view of normality as absence of disease, has been criticised on many grounds. Firstly, it appears to give doctors a lot of power and patients very little (the paternalistic doctor–patient relationship, see later). This is regarded as outmoded as patients are now seen as experts in their own health, and diagnosis and treatment are often a result of negotiation between doctor and patient (see ‘What’s the evidence?’ below).

What’s the evidence?

Breaking bad news

The medical model view of the role of the physician underpinned the development of the authoritarian ‘doctor–patient’ relationship: all authority over health matters was seen to reside in the doctor’s expertise and skill, especially as shown in diagnosis. This meant that the patient’s view of illness and alternative approaches to health were excluded from serious consideration. This is known as the activity–passivity, or paternalistic (‘doctor knows best’), model of doctor–patient relationships (Szasz and Hollander, 1956; McKinstrey, 1992) now regarded as outmoded. Other models of the doctor–patient relationship have been proposed, such as the guidance-cooperation and mutual participation models. As an example of how these models differ, a doctor who is paternalistic is unlikely to be very concerned with the patient’s preferences for treatment whereas this will be very important to a doctor using the mutual participation approach. The role adopted by a doctor depends heavily on the corresponding role adopted by the patient although research shows that, generally, patients are more satisfied with the consultation if they feel you have asked for, and listened to, their views.

Because the major health threats are now not infective diseases but the so-called degenerative diseases (such as heart disease and cancer) and disabling illnesses (such as arthritis and stroke), the medical model is less applicable than was the case when it was first proposed. These conditions are multi-factorial in their development and multi-dimensional in their impact therefore they have neither a simple biological cause nor simple medical or surgical cure.

The medical model also ignores the power of influences other than disease/pathology on health. This is particularly relevant as there is now much scientific evidence that what is considered normal in terms of illness and health may vary by person (individual factors) and by the conditions in which people live (such as living and working conditions). In short, we know now that wider determinants than the presence or absence of disease have an impact on people’s health (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991).

To summarise, what is ‘normal’ is very much in the eye of the beholder. ‘Normal’ in a medical sense is traditionally defined narrowly as absence of disease and/or restoring an organism to normality through eradication of disease. However, changing patterns of disease and mounting evidence that many individual, social and cultural factors influence health have progressed our understanding. While the medical model’s scientific, evidence-based approach is core to good medical practice, a broader model of medicine is required nowadays, one which takes into accoun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword from the Series Editors

- Author Biographies

- Introduction: Jennifer Cleland and Philip Cotton

- Part 1: The Doctor as a Scholar and a Scientist

- Part 2: Applying Knowledge to Clinical Practice

- References

- Index