![]()

| 1 | UNDERSTANDING MENTAL HEALTH AND MENTAL DISTRESS |

This chapter can be used to support the development of knowledge and skills in professional social work as follows:

National Occupational Standards for Social Work

Key Role 1: Prepare for and work with individuals, families, carers, groups and communities to assess their needs and circumstances

- Prepare for social work contact and involvement.

Key Role 3: Support individuals to represent their needs, views and circumstances

- Advocate with and on behalf of, individuals, families, carers, groups and communities.

Key Role 6: Demonstrate professional competence in social work practice

- Managing complex ethical issues, dilemmas and conflicts.

(TOPPS England, 2002)

Academic Standards for Social Work

Honours graduates in social work:

4.4 should be equipped to understand, and to work within, the context of contested debate about the nature, scope and purpose of social work, and be enabled to analyse, adapt to, manage and eventually to lead the processes of change.

4.6 must learn to:

- recognise and work with the powerful links between intrapersonal and interpersonal factors and the wider social, legal, economic, political and cultural context of people’s lives

- understand the impact of injustice, social inequalities and oppressive social relations

- challenge constructively individual, institutional and structural discrimination.

4.7 should learn to become accountable, reflective, critical and evaluative which involves learning to:

- think critically about the complex social, political and cultural contexts in which social work is located.

5.1 should acquire, critically evaluate, apply and integrate knowledge and understanding in relation to:

5.1.1 Social work services, service users and carers

- the social processes (associated with, for example, poverty, migration, unemployment, poor health, disablement, lack of education and other sources of disadvantage) that lead to marginalisation, isolation and exclusion and their impact on the demand for social work services

- explanations of the links between definitional processes contributing to social differences (for example, social class, gender, ethnic differences, age, sexuality and religious belief) to the problems of inequality and differential need faced by service users

- the nature and validity of different definitions of, and explanations for, the characteristics and circumstances of service users and the services required by them, drawing on knowledge from research, practice experience, and from service users and carers.

5.1.4 Social work theory

- research-based concepts and critical explanations from social work theory and other disciplines that contribute to the knowledge base of social work, including their distinctive epistemological status and application to practice

- the relevance of sociological perspectives to understanding societal and structural influences on human behaviour at individual, group and community levels

- the relevance of psychological and physiological perspectives to understanding individual and social development and functioning

- models and methods of assessment, including factors underpinning the selection and testing of relevant information, the nature of professional judgement and the processes of risk assessment and decision-making.

5.5.3 should be able to analyse and synthesise information gathered for problem solving purposes to:

- assess the merits of contrasting theories, explanations, research, policies and procedures

- critically analyse and take account of the impact of inequality and discrimination in work with people in particular contexts and problem situations.

(QAA, 2008)

Key themes in this chapter

- The scope and definitions of mental health and mental distress

- Examining personal attitudes towards mental distress

- The power of language, images and representations of mental health and mental distress

- Theorizing mental health – medical and social models

- Becoming a user of mental health services

- Developing an holistic, user-centred approach to mental health assessment.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter introduces the different terminology, concepts and theories used to describe and understand mental health and mental distress. This is an important starting point as it is vital that practitioners appreciate the diverse, often antagonistic, nature of the language, ideas and explanations that have evolved in this area over time. Pilgrim and Rogers (2005) and Parker et al. (1995) explain that what we know about mental health and mental distress has been influenced in two ways; first through popular culture (everyday language, popular fiction, painting, photography, songs, news and entertainment media) and secondly through professional discourses (psychiatry, psychology, social work and the law). These interact in complex ways producing a powerful fusion of common-sense and ‘scientific’ knowledge that can be difficult to unravel. Therefore this chapter also involves a critical analysis of the relationship between lay and professional knowledge in this field in order to understand the basis of contemporary mental health practice. The process of becoming a user of mental health services is subjected to critical examination, and in particular the process of mental health assessment. As you engage with the materials and exercises you will learn to appreciate that the knowledge base of mental health social work is far from straightforward. Social work practice in this field is inherently complicated, with assessments and interventions often fraught with controversy, tension and contradiction.

DEFINITIONS AND TERMINOLOGY

It is often argued that lay attitudes towards people in mental distress reflect a lack of understanding and knowledge (MIND, 2007a; Thornicroft et al., 2007). For example, surveys of the general public consistently show confusion about what mental distress actually is (DH, 2003a). However, this is not really surprising since there is significant disagreement amongst academics and professionals on this. Ways of understanding and defining mental health and mental distress are constantly changing in what is essentially a contested and dynamic arena. Finding a unified definition of what constitutes mental ‘health’ and mental ‘illness’ can be a frustrating exercise and something of a holy grail. For example, mental health can be defined either negatively, as ‘the absence of objectively diagnosable disease’ (WHO, 1946), or positively, as ‘a state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’ (WHO, 2001a). The Mental Health Act 2007 introduced a single definition of ‘mental disorder’ as ‘any disorder or disability of the mind’.

The confusion and controversy surrounding mental distress is also clearly reflected in the diverse terminology used in the field – mental health; mental illness; mental disorder; mental health problem; mental distress. Although these terms are often used interchangeably, they actually derive from quite different philosophical, theoretical and ideological perspectives. That is, the terminology used to describe a person’s mental health status is grounded in the particular approach to understanding mental health subscribed to by the particular individual, group or organization using the term. So for example, broadly speaking, traditional mainstream psychological or psychiatric literature will opt for the terms mental illness and/or mental disorder in keeping with a psycho-medical paradigm, while critical social scientific or user-centred literature tends towards the terms mental health problem or mental distress reflecting a psycho-social paradigm. These contrasting models of mental health are discussed later in this chapter.

In this book we have shown a conscious preference for the term ‘mental distress’, as this most closely reflects both our value position in relation to people who use mental health services and our critical social scientific approach to the subject. Occasionally we use the terms mental illness and/or mental disorder where we feel it is important to remain consistent with the original context in which the term is used (for example, when discussing official definitions used in mental health law or policy), but when doing so we indicate the contested nature of that term through the use of single inverted commas – as in ‘mental illness’.

EXAMINING OUR ATTITUDES TO MENTAL DISTRESS

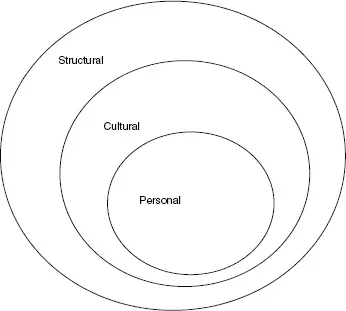

From the outset it is important to acknowledge and reflect on our own individual feelings, attitudes and understanding of mental health and mental distress. Neil Thompson (2006) explains how practitioners need to be aware that they do not practise in a moral and political vacuum. His ‘PCS’ analysis (Figure 1.1) is an extremely useful tool in assisting practitioners to develop their understanding of the relationship between wider society, popular culture and individual attitudes.

Thompson (2006) reminds us that the way we come to understand and behave towards the world around us, and the people within it, is primarily shaped by the culture in which we live. As essentially subjective beings, health and social care professionals are no less immune to the influence of prejudicial ideas, attitudes and behaviours. Acknowledging this fact is an important first step towards becoming a critically self-aware practitioner, capable of identifying and then redressing any personal discriminatory beliefs and practices. We will return to Thompson’s analysis and discuss its application to anti-oppressive social work practice in mental health more fully in Chapter 6.

Figure 1.1 Thompson’s (2006) PCS Analysis

Reflection exercise

How do you feel about people in mental distress? Write down as many words as you can to describe your feelings. Be honest with yourself!

It is highly likely that somewhere on your list the words ‘fear’ and ‘sympathy’ will have appeared, or at least words that convey similar meanings. These are extremely common emotional reactions that people have to those in mental distress. The diverse, complex and extraordinary ways in which mental distress is manifest in human beings can be disturbing, and at times frightening, for those experiencing it, those close to them and those working with them. The UK Department of Health has conducted regular surveys of people’s attitudes to mental distress since 1993 and these two themes have featured prominently and consistently in people’s responses. Moreover, although fear and sympathy might initially appear to reflect quite different value positions, people often express sympathy and concern for the mentally distressed while simultaneously expressing support for actions that effectively stigmatize and exclude them from the rest of society. This reveals how attitudes towards people with mental health problems are extremely complex and often contradictory.

Reflection exercise

How do you feel about your own mental health? Reflecting on your own life experiences, write down some words or phrases to describe your mental health at significant times. Again, be honest with yourself!

Official statistics indicate that one in six people might experience a mental health problem during their lifetime (Singleton et al., 2001). However, in research conducted by the Department of Health (DH, 2003a), 49 per cent of people reported knowing someone who had experienced mental distress, while only seven per cent admitted that they had experienced mental distress themselves. Similarly, in a MORI survey in 1995, 23 per cent of respondents said that if they were receiving psychiatric treatment they would be reluctant or unwilling to admit this to their friends:

It often seems a good idea to keep quiet about my mental distress. Yet when I am asked why I don’t drink or why I took a year out from university, it would be nice to say, ‘I was ill with schizophrenia’ or ‘I take medication for schizophrenia’ without fear of a negative reaction. (Service user, cited in MIND, 2007a)

This suggests that although mental distress is statistically a common experience and part of everyday human existence, we have a tendency to want to distance ourselves from it – to see it as something far removed from us. Furthermore, this seems to confirm the existence of a deep-seated fear of, or taboo around, mental distress in our society: ‘I found that people do one of two things. They look at you in one of two ways. Some look ashamed and furtive because … I suppose everyone talks, and everyone is afraid of madness’. (Nicola Pagett, from Diamonds Behind My Eyes, cited in MIND, 2003a).

There is plenty of historical and cross-cultural evidence to show how the mentally distressed have been feared and excluded from mainstream society. In Madness and Civilisation Foucault tells us how:

Suddenly, in a few years in the middle of the eighteenth century, a fear arose – a fear formulated in medical terms but animated, basically, by a moral myth … the fear of madness grew at the same time as the dread of unreason: and thereby the two forms of obsession, leaning upon each other, continued to reinforce each other. (1967: 192–200)

Denise Jodelet’s (1991) longitudinal research in rural France illustrates the persistence of alienating and exclusionary practices towards the mentally distressed despite their deinstitutionalization and official integration into the community. The rhetorical acceptance of these people into the community was not matched by the reality of their status within it – their ‘otherness’ dictated that they only had a token place in the real world. Similar evidence has emerged from research into the social networks of mentally distressed people discharged into the community in the UK (Repper et al., 1997; Taylor 1994/95) and Ireland (Prior, 1993).

Recent evidence suggests that public attitudes may actually be worsening. In 2007, the Department of Health’s Attitudes to Mental Illness survey found an increase in prejudice across a wide variety of indicators, including: not wanting to live next door to someone diagnosed with mental distress; not believing that the mentally distressed have the same right to a job as anyone else; and believing that they are prone to violence (TNS, 2007). This suggests that very powerful ideological forces are present and that these are in tension with, if not resistant to, progressive social and political developments aimed at improving the lives of the mentally distressed in society. Therefore, our reluctance to admit to experiencing mental health problems in contemporary society is not simply to do with the existential fear of ‘otherness’ – it is as much to do with the material consequences of ‘exposure’ in the form of inequality, discrimination and oppression (Mental Health Media, 2008). As Sayce observes, ‘increasing social inequality … impacts on people with mental health problems both because social exclusion itself creates distress and because those who are disadvantaged by the social status...