![]()

1

What is Action Research?

This chapter focuses on:

- What action research is

- The purposes of conducting action research

- The development of action research

- What is involved in action research

- The models and definitions of action research

- The key characteristics of action research

- The philosophical worldview of the action researcher

- Examples of action research projects.

Introduction

Action research – which is also known as Participatory Action Research (PAR), community-based study, co-operative enquiry, action science and action learning – is an approach commonly used for improving conditions and practices in a range healthcare environments (Lingard et al., 2008; Whitehead et al., 2003). It involves healthcare practitioners conducting systematic enquiries in order to help them improve their own practices, which in turn can enhance their working environment and the working environments of those who are part of it – clients, patients, and users. The purpose of undertaking action research is to bring about change in specific contexts, as Parkin (2009) describes it. Through their observations and communications with other people, healthcare workers are continually making informal evaluations and judgements about what it is they do. The difference between this and carrying out an action research project is that during the process researchers will need to develop and use a range of skills to achieve their aims, such as careful planning, sharpened observation and listening, evaluation, and critical reflection.

Meyer (2000) maintains that action research’s strength lies in its focus on generating solutions to practical problems and its ability to empower practitioners, by getting them to engage with research and the subsequent development or implementation activities. Meyer states that practitioners can choose to research their own practice or an outside researcher can be engaged to help to identify any problems, seek and implement practical solutions, and systematically monitor and reflect on the process and outcomes of change. Whitehead et al. (2003) point out that the place of action research in health promotion programmes is an important and yet relatively unacknowledged and understated activity and suggest that this state of affairs denies many health promotion researchers a valuable resource for managing effective changes in practice.

Most of the reported action research studies in healthcare will have been carried out in collaborative teams. The community of enquiry may have consisted of members within a general practice or hospital ward, general practitioners working with medical school tutors, or members within a healthcare clinic. The users of healthcare services can often be included in an action research study; as such they are not researched on as is the case in much of traditional research. This may also involve several healthcare practitioners working together within a geographical area. Multidisciplinary teams can often be involved (for example, medical workers working with social work teams). Action research projects may also be initiated and carried out by members of one or two institutions and quite often an external facilitator (from a local university, for example) may be included. All the participating researchers will ideally have to be involved in the process of data collection, data analysis, planning and implementing action, and validating evidence and critical reflection, before applying the findings to improve their own practice or the effectiveness of the system within which they work.

Purposes of conducting action research

In the context of this book, we can say that action research supports practitioners in seeking out ways in which they can provide an enhanced quality of healthcare. With this purpose in mind, the following features of the action research approach are worthy of consideration (Koshy, 2010: 1):

- Action research is a method used for improving practice. It involves action, evaluation, and critical reflection and – based on the evidence gathered – changes in practice are then implemented.

- Action research is participative and collaborative; it is undertaken by individuals with a common purpose.

- It is situation-based and context specific.

- It develops reflection based on interpretations made by the participants.

- Knowledge is created through action and at the point of application.

- Action research can involve problem solving, if the solution to the problem leads to the improvement of practice.

- In action research findings will emerge as action develops, but these are not conclusive or absolute.

Later in this chapter we shall explore the various definitions of action research.

Hughes (2008) presents a convincing argument for carrying out action research in healthcare settings. Quoting the declaration of the World Health Organization (1946) that ‘health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’, Hughes stresses that our health as individuals and communities depends on environmental factors, the quality of our relationships, and our beliefs and attitudes as well as bio-medical factors, and therefore in order to understand our health we must see ourselves as inter-dependent with human and non-human elements in the system we participate in. Hughes adds that the holistic way of understanding health, by looking at the whole person in context, is congruent with the participative paradigm of action research. The following extract coming from an action researcher (included by Reason and Bradbury in the introduction to their Handbook of Action Research) sums up the key notion of action research being a useful approach for healthcare professionals:

For me it is really a quest for life, to understand life and to create what I call living knowledge – knowledge which is valid for the people with whom I work and for myself. (Marja Liisa Swantz, in Reason and Bradbury, 2001: 1)

So what is this living knowledge? As Reason and Bradbury (2001: 2) explain, the primary purpose of action research is to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in the everyday conduct of their lives. They maintain that action research is about working towards practical outcomes and that it is also about ‘creating new forms of understanding, since action without reflection and understanding is blind, just as theory without action is meaningless’ and that the participatory nature of action research ‘makes it only possible with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sense making that informs the research, and in the action which is its focus’. Meyer (2000) describes action research as a process that involves people and social situations that have the ultimate aim of changing an existing situation for the better.

In the following sections of this chapter we will trace the development of action research as a methodology over the past few decades and then consider the different perspectives and models provided by experts in the field. Different models and definitions of action research are explored and an attempt is made to identify the unique features of action research that should make it an attractive mode of research for healthcare practitioners. Examples of action research projects undertaken by healthcare practitioners in a range of situations are provided later in this chapter.

The development of action research: a brief background

Whether the reader is a novice or is progressing with an action research project, it would be useful to be aware of how action research has developed as a method for carrying out research over the past few decades. The work of Kurt Lewin (1946), who researched extensively on social issues, is often described as a major landmark in the development of action research as a methodology. Lewin’s work was followed by that of Stephen Corey and others in the USA, who applied this methodology for researching into educational issues. In Britain, according to Hopkins (2002), the origins of action research can be traced back to the Schools Council’s Humanities Curriculum Project (1967–72) with its emphasis on an experimental curriculum and the re-conceptualisation of curriculum development. The most well known proponent of action research in the UK has been Lawrence Stenhouse, whose seminal (1975) work An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development added to the appeal of action research for studying the theory and practice of teaching and the curriculum. In turn, educational action researchers including Elliott (1991) have influenced action researchers in healthcare settings.

What is involved in action research?

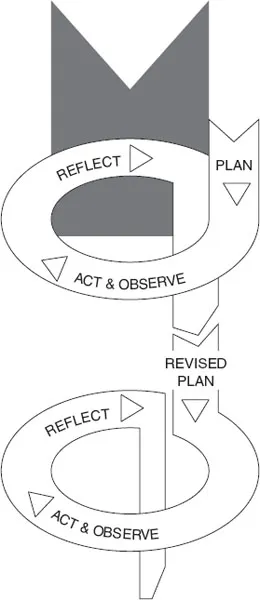

Research is about generating knowledge. Action research creates knowledge based on enquiries conducted within specific and often practical contexts. As articulated earlier, the purpose of action research is to learn through action that then leads on to personal or professional development. Action research is participatory in nature, which led Kemmis and McTaggart (2000: 595) to describe it as participatory research. The authors state that action research involves a spiral of self-reflective cycles of:

FIGURE 1.1 Kemmis and McTaggart’s action research spiral

- Planning a change.

- Acting and observing the process and consequences of the change.

- Reflecting on these processes and consequences and then replanning.

- Acting and observing.

- Reflecting.

- And so on …

Figure 1.1 illustrates the spiral model of action research proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2000: 564), although the authors do not recommend that this is used as a rigid structure. They maintain that in reality the process may not be as neat as the spiral of self-contained cycles of planning, acting and observing, and reflecting suggests. These stages, they maintain, will overlap, and initial plans will quickly become obsolete in the light of learning from experience. In reality the process is likely to be more fluid, open, and responsive.

We find the spiral model appealing because it gives an opportunity to visit a phenomenon at a higher level each time and so to progress towards a greater overall understanding. By carrying out action research using this model, one can understand a particular issue within a healthcare context and make informed decisions with an enhanced understanding. It is therefore about empowerment. However, Winter and Munn-Giddings (2001) point out that the spiral model may suggest that even the basic process may take a long time to complete. A review of examples of studies included in this book and the systematic review of studies using the action research approach by Waterman et al. (2001) show that the period of a project has varied significantly, ranging from a few months to one or two years.

Several other models have also been put forward by those who have studied different aspects of action research and we shall present some of these later in this section. Our purpose in doing so is to enable the reader to analyse the principles involved in these models which should, in turn, lead to a deeper understanding of the processes involved in action research. No specific model is being recommended here and as the reader may have already noticed they have many similarities. Action researchers should always adopt the models which suit their purpose best or adapt these for use.

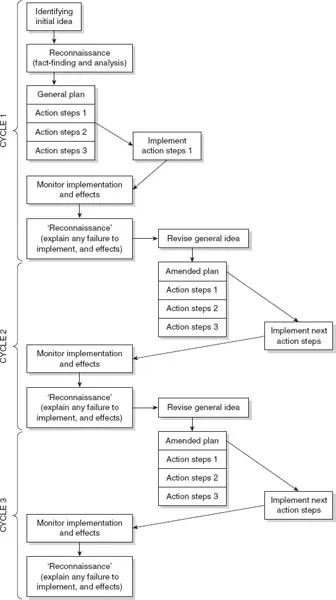

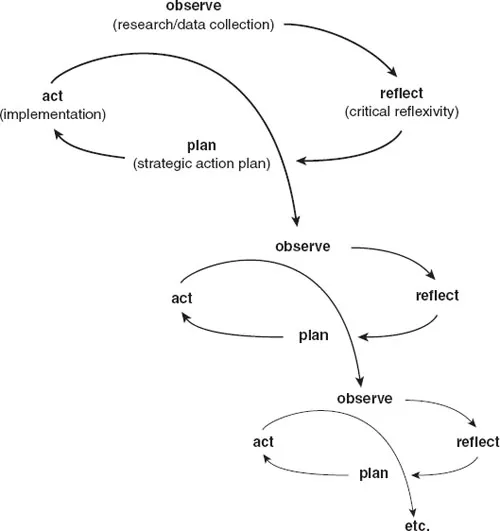

The model employed by Elliot (1991: 71) shares many of the features of that of Kemmis and McTaggart and is based on Lewin’s work of the 1940s. It includes identifying a general idea, reconnaissance or fact-finding, planning, action, evaluation, amending plan and taking second action step, and so on, as can be seen in Figure 1.2. Other models, such as O’Leary’s (2004: 141) cycles of action research shown in Figure 1.3, portray action research as a cyclic process which takes shape as knowledge emerges.

In O’Leary’s model, for example, it is stressed that ‘cycles converge towards better situation understanding and improved action implementation; and are based in evaluative practice that alters between action and critical reflection’ (2004: 140). O’Leary sees action research as an experiential learning approach, to change, where the goal is to continually refine the methods, data, and interpretation in light of the understanding developed in each earlier cycle.

FIGURE 1.2 Elliot’s action research model.

SOURCE: Ellliot, J. Action Research for Educational Change, p.71 © 1991. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Open University Press. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 1.3 O’Leary’s cycles of research

Although it is useful to consider different models, we must include a word of caution here. Excessive reliance on a particular model, or following the stages or cycles of a particular model too rigidly, could adversely affect the unique opportunity offered by the emerging nature and flexibility that are the hallmarks of action research. The models of practice presented in this chapter are not intended to offer a straitjacket to fit an enquiry.

Definitions of action research

Closely related to the purposes and models of action research are the various definitions of action research. Although there is no universally accepted definition for action research, many useful ones do exist. We shall consider some of these in this section. Reason and Bradbury (2006) describe action research as an approach which is used in designing studies which seek both to inform and influence practice. The authors state that action research is a particular orientation and purpose of enquiry rather than a research methodology. They also propose that action research consists of a ‘family of approaches’ that have different orientations, yet reflect the characteristics which seek to ‘involve, empower and improve’ aspects of participants’ social world. A further list of features of action research, put forward by the same authors (2008: 3), states that it:

- is a set of practices that respond to people’s desire to act creatively in the face of practical and often pressing issues in their lives in organizations and communities;

- calls for an engagement with people in collaborative relationships, opening new ‘communicative spaces’ in which dialogue and development can flourish;

- draws on many ways of knowing, both in the evidence that is generated in inquiry and its expression in diverse forms of presentation as we share our learning with wider audiences;

- is value oriented, seeking to address issues of significance concerning the flourishing of human persons, their communities, and the wider ecology in which we participate;

- is a living, emergent process that cannot be pre-determined but changes and develops as those engaged deepen their understanding of the issues to be addressed and develop their capacity as co-inquirers both individually and collectively.

At this point, it may be useful to explore some of the other definitions and observations on action research as a methodology offered by various authors. We define action research as an approach employed by practitioners for improving practice as part of the process of change. The research is context-bound and participative. It is a continuous learning process in which the researcher learns and also shares the newly generated know...