![]()

1

Ethics and journalism?

A reporter is ‘a man without virtue who writes lies . . . for his profit.’

Dr Samuel Johnson

THE REPORTING BESTIARY: WATCHDOGS, VULTURES AND GADFLYS

In polls conducted in 1993 estate agents received the lowest rating in British public esteem; journalists were just above them. And yet the lure of a career in the media is stronger than ever. Reporters repel and attract; they are the twenty-first century equivalent of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the ‘hack’ for whom, in the words of foreign correspondent, Nicholas Tomalin, the only necessary qualifications are ‘a plausible manner, rat-like cunning and a little literary ability (26 October, 1969).’

Little trusted, little loved (but often secretly admired), the reporter is seen as the cynical, ruthless figure parodied in the Channel 4 series Drop the Dead Donkey (1990–98) and films such as Broadcast News (1987) and Network (1976). Described by the satirical magazine, Private Eye, and the Royal Family as ‘the reptiles’, compared to jackals and vultures feeding on human carrion, this image of the journalist reached its apotheosis at the time of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997. The presence and behaviour of the paparazzi at the scene of the accident and Earl Spencer’s public accusation that ‘editors have blood on their hands – I always believed the press would kill her in the end,’ was a low-water mark for British journalism.

Earlier that same year, the white-suited Martin Bell, a former BBC correspondent, won election to Parliament as the unofficial, anti-corruption candidate against the discredited Conservative contender, Neil Hamilton. Here was the journalist as figure of integrity, crusader for truth, exposing evil to the discomfit of the powerful, exemplifed by the Sunday Times’ campaign for justice for victims of the thalidomide drug and John Pilger’s coverage of East Timor.

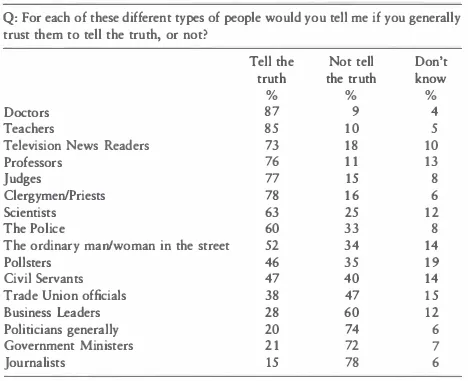

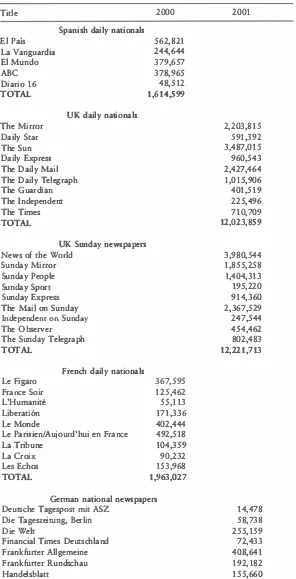

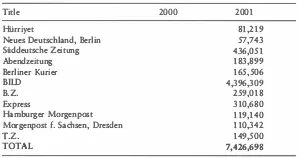

Surveys in Britain show a more favourable perception of broadcast journalists than journalists in general, findings which are reversed in the rest of Europe and the United States. A Harris Poll conducted in the United States in 1998, using virtually identical questions to those asked in a 1997 UK MORI survey, showed that in the United States only 44 per cent of adults say they would generally believe newsreaders, while in Britain 74 per cent would trust newsreaders to tell them the truth. However, only 15 per cent of the British population would trust journalists to tell them the truth compared to 43 per cent of Americans (www.mori.com/polls/1998/harris.html). A MORI survey carried out in February 2000 for the British Medical Association confirmed the British public’s ambivalent attitude to its journalists: 78 per cent of us believe that journalists do not tell the truth, although 73 per cent believe that news readers do (see Table 1.1). And yet we have one of the highest newspaper circulation figures in Europe (see Table 1.2). On an average week-day twelve million copies of national newspapers are sold in Britain, compared to almost two million in France, just over seven million in Germany and about 1.6 million in Spain.

TABLE 1.1 Trust in occupational groups in the UK February 2000

Source: MORI poll in February 2000 on behalf of the British Medical Association. A total of 2,072 adults aged 15 and over were interviewed face-to-face during the period February 3–7 at 156 sampling points throughout Great Britain. Data was weighted to the known profile of the British population (www.mori.com/polls/2000/bma2000.shtml).

As with most caricatures, there is something of truth and much distortion in the Janus-like image we have of journalists. And our continued, although declining, newspaper buying habits point to more ambivalence in our attitudes than the polls would indicate. Nevertheless, few would disagree that British journalists have, in the words of Sky News’ political editor, Adam Boulton (1997), ‘a slightly more Grub Street underbelly’ than their American and continental counterparts, reflecting the vigorous traditions of the popular press (see Engel, 1996; Williams, 1998). Partly for this reason perhaps, they have been less prone to make claims to be a Fourth Estate acting in the national interest. According to this peculiarly British, unromanticized understanding of what journalists do and the impact they can have, journalism is a trade not a profession, journalists are ‘reporters’ and are more gadflys than watchdogs, reptiles than rottweilers.

Scepticism about journalism’s aims and means does not lead to a quiescent industry. The News of The World’s reporters who, in April 2001 exposed the blurring of royal and business affairs in the Countess of Wessex’s PR activities by posing as rich Arabs, could not be further removed from their Spanish counterparts whose own Royals are treated with extreme deference. Journalism in Britain is anything but boring.

However, scepticism exacts a business as well as an ethical price. A resistance to reflection, a permutation of the anti-intellectualism which runs through much of British culture, serves no one. Journalists and editors lose their jobs, people’s lives are badly damaged, share prices are hit and circulation and viewing figures can fall in a climate where reflection on the practices and principles of journalism is actively discouraged.1 As The Times journalist, Raymond Snoddy, put it, ‘talking about and encouraging high standards and ethics in newspapers . . . is not some sort of self-indulgence for amateur moral philosophers or journalists with sensitive psyches: it is a very practical matter, involving customer relations, product improvement and profit’ (1992: 203). This statement stands for all media, although it is undoubtedly the print industry which has been most loath to contemplate the larger implications of what it does.

THE HACK’S PROGRESS

Thinking about ethics is to think about what journalism is and what journalists do. One of the cherished beliefs of most British journalists is that their calling is not a profession nor ever should be. Professional status requires command of a specific area of knowledge which partly determines entry into the profession. Lawyers must know the law. But what body of knowledge is required of the journalist? Journalism, it is said, is more akin to a craft or trade, learned by doing. It should be open to all those who show the right aptitudes, usually summarized as a nose for news, a plausible manner and an ability to write and deliver concise, accurate copy to deadline.

This approach to journalism has meant that journalism training in Britain has been primarily trade-based. Unlike counterparts in the United States and the rest of Europe, training standards have traditionally been set by industry bodies: the National Council for the Training of Journalists (NCTJ) for the print industry and the Broadcast Journalism Training Council (BJTC) for the broadcast industry. Training in skills and knowledge of the law and the workings of government are fundamental. Ethics is not a compulsory separate subject. Training bodies stipulate that ethical reflection be addressed throughout training and that students be fully acquainted with industry codes of practice (the Press Complaint Commission’s Code for the print industry and the BBC’s Producer Guidelines and Codes of the Broadcasting Standards Commission, Independent Television Commission and Radio Authority for the broadcast industry). These training requirements have been incorporated into a variety of diploma courses at non-university institutions. Increasingly they form part of university courses which range beyond the immediate constraints of the traditional industrial training bodies.

The ‘Columbia-Journalism-Review-School of Journalism’, as it has been disparagingly described, arrived in Britain in 1970 when Cardiff became the first university to offer journalism courses (ThomaB, 1998). By 2001 there were 31 undergraduate journalism degrees and six had industry accreditation. This represents an important and not universally welcomed shift in the educational background of journalists.2

TABLE 1.2 National newspaper circulation in Europe, 2000/2001

Sources: Audit Bureau of Circulation, Oficina de Justificación de Difusión, Informationsgemeinschaft zur Feststellung der Verbgreitung von Werbetagern (IVW) and Associacíon pour le Controle de la Diffusion des Média.

Some fear that the shift to university-based education might blunt the edge of hard reporting in the same way that journalism schools are said to have done in the United States. The legendary publisher of the National Enquirer, Generoso Pope, was said to prefer British journalists to American ones because they hadn’t forgotten that they were in the business to sell newspapers and not simply to right the wrongs of society. This gave their reporting bite so that, according to one journalist, an American reporter sent to a plane crash would write, ‘I wept over the funeral pyre of 199 people,’ whereas his/her British counterpart would write, ‘Dead, that’s what 199 people were last night’ (Taylor, 1991: 59). But (and this will be the central contention of this book) being a reflective journalist isn’t inimical to good reporting. If we consider what skills and knowledge journalists should have, the reverse is likely to be true.

SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

In 1996 US newsroom supervisors were polled to see what importance they gave to different knowledge and skill areas for the potential journalist (Medsger, 1996: 25). The ten areas which received most approval were:

- Basic newsgathering and writing skills – 98%

- Clear writing skills – 97%

- Understanding that accuracy and truthfulness are essential in journalism – 96%

- Interviewing skills – 95%

- Analysing information and ideas – 94%

- Ability to organize complex stories with clarity and grace – 86%

- Writing on deadline – 82%

- Well-informed about current events – 78%

- Ability to recognize holes in coverage – 77%

- Ability to develop story lines on your own – 76%

The American editors’ list of qualities falls across several of the categories of understanding of knowledge identified by Aristotle as (i) episteme: scientific knowledge; (ii) tekne: art – making knowledge; (iii) phronesis: practical knowledge; (iv) sophia: philosophical knowledge; (v) nous: intuitive reason. They can help us to structure and understand the kind of knowledge journalists should have.

(i) Technical knowledge: The aim here is to learn how to do something. And, of course, the best way of learning how to do something is by doing it. Providing you with a theoretical book on how to ride a bicycle will be of little use in riding a bicycle. You will only learn how to cycle by cycling. Learning shorthand is an example of this kind of knowledge.

(ii) Practical knowledge: Ethics, politics and rhetoric, the art of persuasion, all require practical knowledge, knowing how to act, how to apply one’s intellectual capacities in order to achieve the right outcome in the area concerned. A good doctor must not only know how to use a stethoscope but also have acquired intellectual habits of judgement and discernment which allow him/her to discriminate between chicken pox and what is just a particularly mottled complexion, and then prescribe the appropriate remedy.

Practical knowledge is about the correct application of acquired intellectual habits to one’s chosen field for the attainment of particular goals. A journalist has to know what the story is and then know how to tell it. This involves technical knowledge but also powers of judgement and analysis: decisions about use and credibility of sources, appropriateness of tone, story interest, none of which are givens. Getting a story right, as the Sunday Mirror editor, Colin Myler, found over the Leeds football players’ trial in spring 2001, can be critical to job security, a paper’s reputation and share prices (see note 1).

(iii) Philosophical knowledge: In third place on the American editors’ list of qualities was the awareness that accuracy and truthfulness are essential to the journalist’s task. To understand why this should be considered so is to enter the realm of philosophical knowledge. Questions about what a journalist is and what reporting is for, are the often unexplored assumptions underlying practice. The view of one tabloid editor that, ‘Information is only a commodity, like bread’ will almost certainly influence the kind of stories printed in his paper.

Reflecting on ethics and journalism is about acquiring philosophical knowledge which is of intrinsic interest, self-sufficient, complete in itself. It is to say that education is more than training.

In this sense, reflection on ethics and journalism is distinctly out of tune with the temper of our utilitarian times. For it requires us to move beyond what the political philosopher, Michael Oakeshott (1993), has spoken of as the condition of worldliness, the thought that what matters above all is success understood as the achievement of some external result, usually striving to have a successful career as evidence of achievement. Of course, there is nothing wrong with having a successful career. Oakeshott’s point is that an excessive concern with reputation can mean that the present is sacrificed to the god of the future; he suggests that it is preferable that: ‘Ambition and the greed for visible results, in which each stage is a mere approach to the goal . . . be superseded by a life which carried in each of its moments its whole meaning and value’ (1993: 32). Lofty words and, some might say, unrealizable aims yet they express what many have felt to be true about human existence.

Episteme and nous have been left outside this account: the first, because there is no knowledge area (although it is possible, but not wise, to be a reporter without knowing any law) which a journalist must master (unless of course he or she is a specialist correspondent); the second, because intuitive knowledge is just that: it can be tutored and nurtured but either you’ve got it or you haven’t. Technical and practical knowled...