eBook - ePub

Developing Primary Mathematics Teaching

Reflecting on Practice with the Knowledge Quartet

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Developing Primary Mathematics Teaching

Reflecting on Practice with the Knowledge Quartet

About this book

How can KS1/2 teachers improve their mathematics teaching? This book helps readers to become better, more confident teachers of mathematics by enabling them to focus critically on what they know and what they do in the classroom. Building on their close observation of primary mathematics classrooms, the authors provide those starting out in the teaching profession with a four-stage framework which acts as a tool of support for developing their teaching:

- making sense of foundation knowledge - focusing on what teachers know about mathematics

- transforming knowledge - representing mathematics to learners through examples, analogies, illustrations and demonstrations

- connection - helping learners to make sense of mathematics through understanding how ideas and concepts are linked to each other

- contingency - what to do when the unexpected happens

Each chapter includes practical activities, lesson descriptions and extracts of classroom transcripts to help teachers reflect on effective practice.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Inside Naomi’s Classroom

In this chapter you will read about:

- the focus of the book on teachers’ knowledge;

- the distinction between mathematical content knowledge and generic knowledge;

- how teachers can develop knowledge for mathematics teaching;

- a particular lesson on subtraction taught by a student teacher.

This book is about some of the things that teachers know, that help them to teach mathematics well. There will be some ‘theory’, but most of the book is rooted firmly in real classrooms, with some teachers and pupils who helped to make the book possible. In fact, we shall visit one of these classrooms very soon.

Teachers are very serious about their work, and constantly want to get better at what they do. This improvement comes about through a variety of influences. You might want to pause a moment to think what these influences include, and list a few of them.

One obvious possibility is ‘experience’. We hope to get better at doing something simply by doing it. So we might imagine that our teaching of, say, mental addition strategies would be better in our second year of teaching than it was in the first, and so on. This may well be the case, although it is worth asking why it should, or what would help to make it more likely that it would. At the very least, you would need to be able to recall what you learned from your last experience of teaching mental addition strategies – what seemed to work well, and what did not. Fortunately, we learn a lot from things that do not go well, because we want to avoid them happening again. The key to all this is what is usually called ‘reflection’ on practice. Teachers’ open-mindedness and their desire to do a good job lead them to look for reasons for their actions in the classroom, and to analyse the educational consequences of those actions. Donald Schön’s term ‘reflective practitioner’ (Schön, 1983) is often used to conjure up the notion of teachers as professionals who learn from their own actions – and those of others. Schön distinguished between two kinds of reflection. The first, reflection on action, refers to thinking back on our actions after the event. Most of this book is about that kind of reflection, and we promote the idea that it is most fruitful to reflect on action with a supportive colleague who observed you teaching mathematics. The second kind of reflection is what Schön called reflection in action, being a kind of monitoring and self-regulation of our actions even as we perform them. This is also something that we think about in this book, especially in Chapter 6. Because reflection in action is especially difficult, a supportive observer can also be helpful in drawing attention to opportunities or issues that the teacher may have missed, often because their attention was on something more urgent.

We should also point out, from the outset, that in observing and commenting on someone else teaching, the supportive observer stands to learn as much as, or more than, the one being observed. This book is witness to this claim. We could not have written it, and we would not have learned much of what we have to say in the book, without the benefit of a great deal of supportive observation of other teachers teaching mathematics. If we take any credit, it would be for our own efforts at reflection on other teachers’ actions in the past, and on and in our own teaching more recently.

In this spirit, then, this book offers you the opportunity to ‘observe’ other teachers and to reflect on what they do. Your observation may be fairly direct, because some lesson excerpts can be watched as video clips. Others will be ‘observed’ as you read succinct accounts of them and read some verbatim transcript selections. The advantage of the transcripts is that you can easily revisit and dissect them if you wish. With few exceptions, these teachers whom you will observe are relatively inexperienced, and their lessons are not offered as models for you to copy. You can read about why we videotaped these lessons in Chapter 2. Sometimes you will think that a teacher could, or should, have done something differently. As we have already said, you will learn something merely by thinking, and especially by making, that reflection explicit in discussion, or in a written note of some kind. Paradoxically, you would learn very little from commenting that ‘it went well’.

In the UK, many graduate student teachers (sometimes called ‘trainees’) follow a one-year, full-time course leading to a Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) in a university education department. About half the year is spent teaching in a school under the guidance of a school-based mentor. All primary trainees are trained to be generalist teachers of the whole primary curriculum. The mathematics lessons featured in this book were filmed while the teachers were in their PGCE year or in the early stages of their teaching career. The index of teachers and lessons on pp. x–xiii summarises where each teacher’s lesson occurs in the book along with the career stage of the teacher, an indication of the mathematical content, the part of the lesson and, where appropriate, the video clip number on the companion website.

In this chapter, you will observe a lesson on subtraction. The pupils, boys and girls, are in Year 1 (age 5–6 years). The teacher is Naomi, who was, at the time, a PGCE student in the third and final term of her course. For most of that term, she was on a teaching placement in a primary school. Naomi chose to specialise in early years education in her PGCE. In most of the UK, it is usual to study only three or four subjects at school between 16 and 18. At school, Naomi had specialised in mathematics, English, French and psychology. Relatively few primary PGCE students have undertaken such advanced study in mathematics. Following school, Naomi’s undergraduate degree study had been in philosophy.

In this book, we will sometimes ask you to read a description of a lesson, or part of a lesson. Sometimes we will give verbatim transcripts of short lesson episodes. In the case of the lesson featured in this chapter, you can also view a video clip (Clip 1) on the companion website if you wish.

Naomi’s lesson

Naomi’s classroom is bright and spacious, with a large, open, carpeted area. We can see around 20 young children in the class: there might be a few more off-camera. There is also a teaching assistant positioned among the children. The learning objectives stated in Naomi’s lesson plan are: ‘To understand subtraction as “difference”. For more able pupils, to find small differences by counting on. Vocabulary – difference, how many more than, take away.’ Naomi notes in her plan that they have learnt how many more than.

Naomi settles the class in a rectangular formation around the edge of the carpet in front of her, then the lesson begins with a seven-minute oral and mental starter designed to practise number bonds to 10. A ‘number bond hat’ is passed from child to child until Naomi claps her hands. The child wearing the hat is then given a number between 0 and 10, and expected to state how many more are needed to make 10. Naomi chooses the numbers in turn: her sequence of starting numbers is 8, 5, 7, 4, 10, 8, 2, 1, 7, 3. When she chooses 8 the second time, it is Bill’s turn. Bill rapidly answers ‘two’. Next it is Owen’s turn:

| Naomi: | Owen. Two. |

| [12-second pause while Owen counts his fingers] | |

| Naomi: | I’ve got two. How many more to make ten? |

| Owen: | [six seconds later] Eight. |

| Naomi: | Good boy. [addressing the next child] One. |

| Child: | [after 7 seconds of fluent finger counting] Nine. |

| Naomi: | Good. Owen, what did you notice … what did you say makes ten? |

| Owen: | Um … four … |

| Naomi: | You said two add eight. Bill, what did you say? I gave you eight. |

| Bill: | [inaudible] |

| Naomi: | eight and two, two and eight, it’s the same thing. |

Later, Naomi gives two numbers to the child with the number bond hat. The child must add them and say how many more are then needed to make 10.

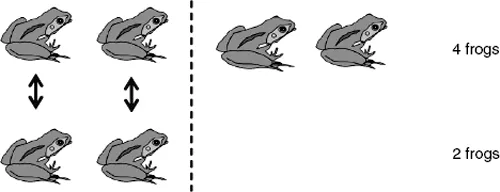

The introduction to the main activity lasts nearly 20 minutes. Naomi wants to introduce them to the idea of subtraction as difference, and the language that goes with it. To start with, she sets up various difference problems, in the context of frogs in two ponds. Magnetic ‘frogs’ are lined up on a board, in two neat rows. In the first problem, Naomi says that her pond has four frogs, and her neighbour’s pond has two, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Note: the arrows and dotted line have been added for clarity.

Figure 1.1 | Naomi’s representation of the frogs |

| Naomi: | I went to my garden this weekend, and I’ve got a really nice pond in my garden, and when I looked I saw that I had … [Naomi tries to stick some ‘frogs’ on the board] … I don’t think they’re sticking. Let me get some Blu-tack. It’s supposed to be magnetic, but it doesn’t seem to be sticking. Right. I had four frogs, so I was really pleased about that, but then my neighbour came over. She’s got some frogs as well, but she’s only got two. How many more frogs have I got? Martin? |

| Martin: | Two. |

| Naomi: | Two. So what’s the difference between my pond and her pond in the number of frogs? Jeffrey. |

| Jeffrey: | Um, um when he had a frog you only had two frogs. |

| Naomi: | What’s the difference in number? […] this is my pond here, this line – that’s what’s in my pond, but this is what’s in my neighbour’s pond, Mr Brown’s pond, he’s got two. [Gender of neighbour has changed!] But I’ve got four, so, Martin said I’ve got two more than him. But we can say that another way. We can say the difference is two frogs. There’s two. You can take these two and count on three, four, and I’ve got two extra. Right, let’s see who wants to be my helper. |

| A couple of minutes later, Naomi says: | |

| Naomi: | Morag’s been sitting beautifully, oh no, Morag’s been reading a poetry book. […] That should be on my desk, thank you. Put your hand up please, you know the rule. Yes Hugh? |

| Hugh: | You could both have three, if you give one to your neighbour. |

| Naomi: | I could, that’s a very good point, Hugh. I’m not going to do that today though. I’m just going to talk about the difference. Morag, if you had a pond, how many frogs would you like in it? |

Pairs of children are invited forward to choose numbers of frogs (e.g. 5, 4) and to place them on the board. The differences are then explained and discussed.

Before long, Naomi asks how these differences could be written as a ‘take away sum’. With assistance, a girl, Zara, writes 5 − 4 = 1. Later, Naomi shows how the difference between two numbers can be found by counting on from the smaller.

The children are then assigned their group tasks. The usual class practice is to group the children by ‘ability’ for mathematics. The actual numbers used in the difference problems are the same for each group, but the activity is differentiated by resource. One group (called the Whales), supported by a teaching assistant, has been given a worksheet on which drawings of cars, apples and the like are lined up on the page, as Naomi had done earlier with the frogs. Two further groups (Dolphins and Octopuses) have difference problems set in ‘real life’ scenarios, such as ‘I have 8 sweets and you have 10 sweets’. These two groups are directed to use multilink plastic cubes to solve them, lining them up and pairing them, as Naomi had done with the ‘frogs’ in her demonstration. The remaining two groups have a similar problem sheet, but are directed to use the counting-on method to find the differences. Naomi works with individuals.

In the event, the children in the Dolphin and Octopus groups experience some difficulty working with the multilink. This is partly because ‘lining up’ requires some manual dexterity, and also because the children find more interesting (for them) things to do with the interlocking cubes. Naomi comes over to help the Dolphins. She emphasises putting eight cubes in a row, then ten. ‘Then you can see what the difference is.’ She demonstrates again, but none of the children seems to be copying her. Jared can be seen moving the multilink cubes around the table, apparently aimlessly. Another child says ‘I don’t know what to do’. Naomi moves away to give her attention to the Octopuses. In her absence from the table, one boy sets about building a tower with the cubes. Later, Naomi returns to the Dolphins, and tries once again to clarify the multilink method. She asks: ‘What’s the difference betw...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Index of teachers and lessons

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Inside Naomi’s classroom

- 2 Knowledge for teaching mathematics: introducing the Knowledge Quartet framework

- 3 Transformation: using and understanding representations in mathematics teaching

- 4 Transformation: using examples in mathematics teaching

- 5 Making connections in mathematics teaching

- 6 Contingency: tales of the unexpected!

- 7 Foundation knowledge for teaching mathematics

- 8 Using the Knowledge Quartet to reflect on mathematics teaching

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Developing Primary Mathematics Teaching by Tim Rowland,Fay Turner,Anne Thwaites,Peter Huckstep in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Teaching Mathematics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.