![]()

| | General principles of criminal law |

![]()

| Introduction and rationale: why study criminal law if you’re a criminology or criminal justice student? |

| Criminal law: what is it? |

| Criminal justice: what is it? |

| What is the criminal law there for? |

| What is criminal justice there for? |

| Conclusions: a guide to the structure of the book |

| Further reading |

Chapter Aims

After reading Chapter 1 you should be able to understand:

- The basic principles of criminal law

- The basic principles of criminal justice

- The key theories which try to explain what the criminal law does

- The key theories which try to explain what criminal justice does

- Which individuals and groups of people play a role in criminal justice

- How crime is socially constructed, and what this means

Introduction and rationale: why study criminal law if you’re a criminology or criminal justice student?

This book is about criminal law in England and Wales, and the difference between the criminal law as it is defined in law books, and the criminal law as it is used by agencies in the criminal justice process. It is designed to show not only how the current law defines criminal behaviour, but also how people and organisations working in criminal justice use and interpret that law in the approaches they take to responding to crime in practice.

One answer to the question in the section title above is simple – without criminal law there would be no crime and no criminology (Nelken 1987)! It is the criminal law which ‘labels’ certain kinds of behaviour as being unlawful, and sets out the rules for deciding when a crime has been committed. The organisations who have responsibility for responding to crime use these rules as guidelines for using the state’s power to respond to crime.

The question then is: to what extent do the criminal justice organisations stick to the rules set out by the criminal law? Some criminologists have argued (e.g. McBarnet 1981) that the police and other criminal justice organisations use their own power, discretion and ‘working rules’ far more than they use the criminal law itself. It is this gap between the ‘law in the books’ and ‘the law in action’ (Packer 1968) which is the main subject of this book. To understand criminology and criminal justice fully, it is necessary to compare the criminal law with criminal justice practice. In other words, this book aims to bridge the gap between criminal law and criminal justice, to provide a better understanding of both subject areas.

The next section of this chapter introduces criminal law in England and Wales.

Criminal law: what is it?

DEFINITION BOX 1.1

CRIMINAL LAW

Law which defines certain types of behaviour as being criminal, and allows those types of behaviour to be punished in some way by the state.

Substantive criminal law is the part of the law that deals with behaviour which is defined as criminal, and results in punishment by the state when a person is found to be guilty of breaking the law. It is separate from what Uglow (2005: 448) calls procedural criminal law, which defines and regulates the powers of criminal justice agencies to investigate, prosecute and punish crime. Substantive criminal law is also separate from civil law, which deals with other forms of behaviour that result in some form of compensation (often payment of money) after a finding of guilt. A key difference between substantive criminal law and civil law lies in the standard of proof needed to find guilt in each case. For criminal law, guilt is proved by evidence of guilt beyond reasonable doubt. For civil law, guilt is proved by evidence of guilt on the balance of probabilities, which requires a lower standard of proof, and therefore less evidence indicating guilt, than proof beyond reasonable doubt. Linked to this is the idea of the burden of proof being on the prosecution (Woolmington v DPP [1935] AC 462). This means that the defendant in a criminal case (defendants will be referred to from now on in the book as ‘D’) is innocent until the police and prosecutors have enough evidence to prove beyond reasonable doubt in court that D is guilty of all the different elements of the criminal charge(s) brought against them. Traditionally, this means that they will have to prove the guilty conduct (actus reus) specified by the definition of the offence, and also the guilty state of mind (mens rea) which is specified. The principle is the foundation of the adversarial system of criminal justice that has been established in England and Wales, where the prosecution and defence compete against each other to persuade the courts that their evidence is more convincing than the other side’s.

Related to the rule regarding the burden of proof is the principle of the rule of law, which is equally fundamental to understanding criminal law and criminal justice in England and Wales. Under the rule of law, no one can be punished unless they have breached the law as it is clearly and currently defined, and they have been warned that the conduct they have been accused of is criminal (Rimmington [2006] 1 AC 459); the breach is proved in a court of law; and everyone (including those who make the law) is subject to the rule of law, unless special status is given by the law itself (Simester and Sullivan 2007: chapter 2).

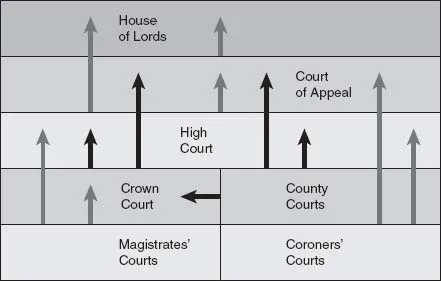

Criminal law in England and Wales, under the rule of law, comes from three main sources. The first is known as common law. This is law which is made and developed by judges when they decide cases, in line with the rules on precedent. Precedent means that a particular court has to follow an earlier court’s decision which is based on the same law and the same facts as the case it is currently deciding, and which was made at a higher court level or (usually) at the same level as itself, but it does not have to follow decisions made at lower levels. Figure 1. 1 shows how court decisions are appealed to higher courts in England and Wales, and how precedent works.

Figure 1.1 The court appeal system in England and Wales

The second source of criminal law is known as statute law. This is law which is created by Parliament, and implemented in the form of Acts of Parliament, or statutes. Statute law is often used to decriminalise old offences, create new offences, redefine or change criminal offences which already exist, or bring together old pieces of legislation on the same topic. All new criminal offences must now be created by statute law, not by the courts through the common law (Jones and Milling [2007] 1 AC 136), although courts used to be able to use common law to create offences, and some offences are still defined by common law today, such as murder. However, even where a criminal offence has been defined by statute, courts will often decide the details of that offence through their own case-by-case decisions, especially where there is some confusion over what a statute (or part of a statute) means in practice.

The third source of law is law which is developed from the obligation of substantive criminal law to comply with European human rights law as contained in the European Convention on Human Rights (‘ECHR’ from now on in this book). Since Parliament passed the Human Rights Act 1998, individuals have the right to complain to courts in England and Wales where they feel that their human rights have been breached by substantive criminal law. The occurrence of miscarriages of justice, for example, where a person is convicted and punished for a criminal offence which they did not commit, involves serious breaches of human rights (e.g. Walker and Starmer 1999). As a result of the Human Rights Act, courts must interpret statute law in a way which is compatible with human rights legislation (s. 3). If this cannot be done, the courts must make a declaration of incompatibility regarding the piece of law being challenged, and pass the issue on to Parliament so that it can redefine the law in a compatible way (Buxton 2000). Section 6 of the Human Rights Act requires public authorities, including the police, the Crown Prosecution Service and the courts (see below), to act in a way which is compatible with the ECHR, and also allows common law to be changed in line with the ECHR (H [2002] 1 Cr App Rep 59).

STUDY EXERCISE 1.1

List three features of the substantive criminal law as it operates in England and Wales.

Substantive criminal law, in all its forms, is developed by the decisions of individuals and organisations. Therefore, what counts as ‘crime’ can and does change over time. The criminal law-making policy of the New Labour government since 1997 illustrates this very clearly. By September 2008, New Labour had created 3,605 new criminal offences – one for almost every day the government had been in power (Morris 2008). The criminalising of hunting wild mammals with dogs, under the Hunting Act 2004, is just one high-profile (and controversial) example of a crime created by New Labour. On the other hand, there are types of behaviour which used to be crimes, but which no longer are – such as the Sexual Offences Act 1967, which partially decriminalised homosexual behaviour between adult men. From these examples it can be seen that crime itself is a ‘social construct’ (Muncie 2001). No behaviour is criminal until an individual or group of people decides to make it criminal (Christie 2004). As a result, the boundaries of criminal behaviour have changed constantly over time, in line with changes in public opinion, political parties’ views, and social and economic conditions (Lacey 1995). This has often caused confusion and inconsistency in the criminal law.

STUDY EXERCISE 1.2

Using Internet resources and statute books, find three examples of offences which have been decriminalised, and three examples of offences which have been created since 1997 by the New Labour government. Why do you think each of these offences has been criminalised or decriminalised? Do you agree with the decision to criminalise or decriminalise eac...