![]()

Section 1

Quality Improvement: Process or Product?

![]()

1

What do we mean by quality and quality improvement?

Michael Reed

Chapter overview

This chapter offers a broad introduction to the concept of quality in early childhood education and what is meant by quality improvement. It sets the scene for what follows in the remainder of the book where illustrations of quality and debates about what constitutes quality are provided about aspects of early years education. It is unable to offer a single definition of what is meant by ‘quality’ as this is open to interpretation and is often mitigated by variables that influence how we define and refine quality. It attempts to examine the large volume of literature surrounding quality, and the professional dispositions that also impact upon quality. It argues that these need to be understood and closely examined, which will in turn help to establish what we mean when we consider ‘quality in practice’.

From professional competency to quality improvement – a journey of reflection

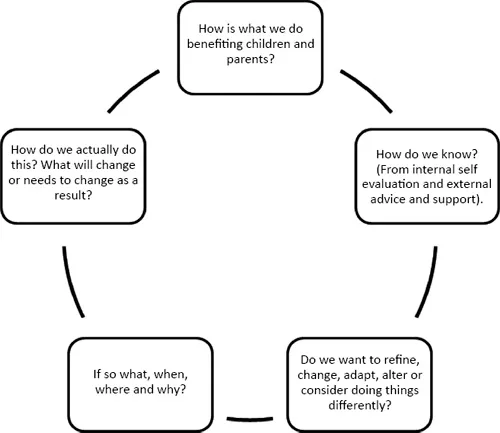

Quality improvement is a continuous process rather than a single event. It is a process of evaluating aspects of practice to enhance and support the well-being of children and families. It involves the whole of an early years setting and is a complement and extension to the inspection process. Importantly, it is a way of self-evaluating what goes on in order to make things better. It requires listening to the views of those most closely involved, including children, and identifying key aspects for improvement. This also involves listening to external advice, recognising internal strengths and realising that any action as a result of this process may well change what people in an organisation say and do. It is often formalised into a pattern illustrated as a cycle of questions (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Evaluating practice to identify quality

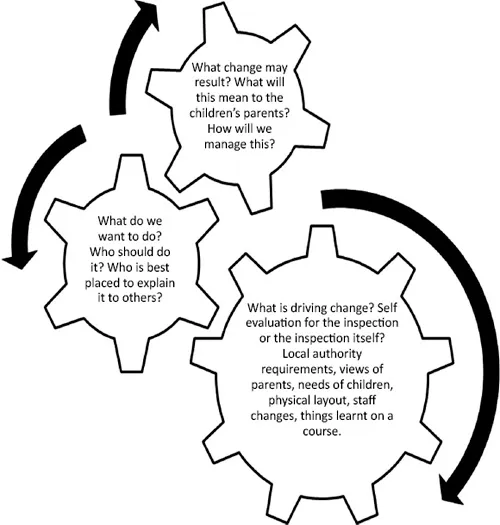

However, this representation can be challenged as being too simplistic. In an early years setting, things are rarely so logical and focused. What happens in reality is that ideas, views, responses and challenges are a constant part of everyday life. As a consequence there is a danger that we can easily become reactive and not find the time to sit back and carefully consider what we do well and what we need to improve. There is also a danger that quality improvement is resisted. This is because in part it can be seen as being asked to refine or enact another form of ‘guidance’ or ‘directive’ from government or government agency. On the other hand, it seems that practitioners can and do welcome the responsibility of wanting to do their best for families and communities and they are willing to learn from the numerous information sources they are expected to look at. Perhaps we should see evaluating practice more like the cogs of a wheel, where answering one question leads to another and another so that a cascade of evaluation is triggered to support reflection on quality improvement (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The ‘cogs’ of reflection to support quality improvement

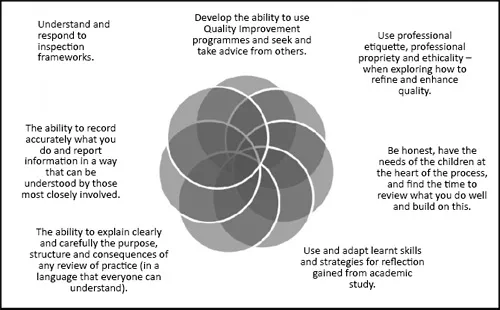

Ideas for change and improvement are seldom seen on their own; they are interrelated and influence each other. We also have to prioritise and consider why doing one thing for the right reasons may well influence or have a marked impact on another part of an organisation, which can sometimes be positive but might equally be problematic. Therefore quality improvement requires less reaction, more reflection and much more evaluation and planning. It is often linked to change and the ability of practitioners to lead and manage change. It requires the skills of investigation and an understanding of ‘research’ processes in the workplace (Costley et al., 2010; Callan and Reed, 2011). This is because improving quality is indeed a process and not an activity that can be ‘done’ or ‘ordered’; it requires practitioners to use all of their inherent and interrelated skills, such as those outlined in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Using interrelated skills to support a quality process

As valid as Figures 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 may be, in terms of representing the processes of quality improvement they do not tell us what ‘quality’ is or looks like. It is here that the debate about what constitutes quality begins. To many practitioners the debate may seem one-sided as they try to respond to government and curriculum ‘quality indicators’ as well as the demands of inspections, which result in a setting seen as having ‘good or outstanding features’. The debate asks practitioners to somehow choose between what they in their local context see as quality and what external agencies, regulatory bodies and researchers see as quality. The debate also encompasses how children learn, and how best they can be encouraged to learn, and has yet to reach a conclusion. It has always fascinated writers, researchers, psychologists, teachers, parents and policy-makers. It has also captivated philosophers, spiritual leaders and those who study the social world of the child and family. The result has been an intense study of child development over many decades, which we would suggest is well explained by a detailed review of the research literature (Evangelou et al., 2009). We recommend reading the whole review but have selected some examples that start to tell us what quality experiences aid children’s development:

- Children’s development is dependent upon a wide range of interrelated factors.

- Developmental theories have been linear, with children said to follow similar pathways to adulthood, but new theories assume that development proceeds in a web of multiple strands, with different children following different pathways.

- Children are born without a sense of self; they establish this through interactions with others (adults, siblings and peers) and with their culture.

- Children thrive in warm, positive relationships.

- Play is a prime context for development.

- Conversation is a prime context for development of children’s language, and also their emotions.

- Narrative enables children to create a meaningful personal and social world, but it also is a ‘tool for thinking’.

- The early years curriculum needs to provide opportunities for problem-solving to develop logical mathematical thinking.

- Children’s self-regulation requires the development of opportunities, which facilitates the internalisation of social rules.

- Cultural niches and repertoires are important considerations in shaping the context of children’s learning.

- The concept of children’s ‘voice’ is not new but has become an increasing focus of research.

- Enhancing children’s development is skilful work, and practitioners need training and professional support.

- The quality of both the home learning environment and the setting have measurable effects on children’s development.

- Quality includes relationships and interactions, but also pedagogical structures and routines for learning.

- Formative assessment is at the heart of providing a supporting and stimulating environment.

- Professional development is important for practitioners, as is liaison with agencies outside the setting.

- New research has focused on the benefits of using technology and their use in communicating between the setting and home.

This gives us our first glance at what is meant by quality. Nevertheless, it only represents the findings from a review, however sophisticated. As it suggests, there are many interrelated and complex factors that come into play when considering the way children grow and develop, and as for defining the ‘best way’ that might lead to ‘best quality’ there are certainly no easy answers.

Defining quality, explaining quality, demonstrating quality: no easy answers

Quality is influenced by our own perspectives on learning as well as by what we have read, observed and practised. We are also influenced by our position in a particular early years context or landscape. Sometimes we may be insiders operating and reflecting in an early years setting. At other times we are outsiders looking at what goes on through the eyes of what is expected by regulation or any other determinant of what is thought to be good practice. This is what Katz (1994) describes as seeing things from different perspectives, be this a parent, practitioner or visitor. This view is refined by Armistead (2008) who uses the terms ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ in developing an argument about using children’s voices as determinants of quality. To this we can add differing interpretations or theories proposed by early education pioneers such as Rousseau through to Montessori and Piaget through to Vygotsky (Mooney, 2000; Robinson, 2008). They all observed children and reached quite varied conclusions about how children learn and how adults promote learning. Their views are influential and have contributed to the design of early years curriculum frameworks in all nations of the United Kingdom.

Views about quality also come from researchers such as Taguchi (2010), who provides ideas that prompt us to consider and reconsider the way children learn and the interactivity between the world around us. Such views open up further debate by encouraging us to reflect, learn and challenge what we know and think. For example, Dahlberg et al. (2007) and Dahlberg and Moss (2008) offer a view of quality that challenges assumptions about the term, what it means and how it can be seen. Dahlberg et al. (2007: 106) see the present and dominant ‘discourse of quality’ with the ‘discourse of meaning making’ requiring dialogue and critical reflection grounded in concrete human experiences and recognising that we all see the world from differing positions and contexts. They put forward a thought-provoking series of arguments that underline a view that people have different views of what educational outcomes should be considered as quality, and how they are reached. This differs from the body of knowledge about quality that predominates, much of it emanating from the USA. It suggests that quality practice and provision can be examined in terms of its longer-term effects on children’s learning and development and that it revolves around those aspects that can be monitored, changed and imposed by regulators and government.

Myers (2005) provides a summary of these positions from the perspective of emergent and emerging economies and argues that quality early learning is based upon evidence from scientific positions that see quality as inherent in practice, identifiable and universal. He suggests that quality experiences have a pronounced effect on children’s language and cognitive development but also involve effects on social development and behaviour. Although children may benefit, there is evidence that disadvantaged children may profit the most and the quality of the structure of organisations has an effect on outcomes. He recognises that although high quality is important it is also possible to find significant and even dramatic effects of programmes that are of minimal quality, judged by standards of the minority world. We should therefore see quality as being debated on a much wider front than northern Europe and the USA. For example, the work of Tikly and Barrett (2007: 15) considers quality measures related to sub-Saharan Africa and they assert that any ‘understanding of education quality must consider local realities and be related to analysis of how the broader historical, socio-economic, political and cultural context interacts with educational processes’. We need to remember that contextual factors are important locally, nationally and internationally and the quality of the relationship between settings and families needs to be consciously developed as part of quality improvement. Quality should also be seen in relation to promoting access to early childhood support and therefore having quality in place without access for disadvantaged groups is not productive.

Sylva and Roberts (2010) provide a view of the methods of observing and measuring quality and its longer-term effects. The research considers health and growth, social and emotional development, and cognitive and educational development in a range of settings including care by grandparents, other relations or friends, and care by nannies or childminders. The research looks at the more subtle aspects of quality, for example gender, as well as such aspects as the relationship between a mother or caregiver and the child. It is based in the UK and therefore offers an alternative perspective to research from the USA where standards and types of provision are different. It also considers outcomes for children and probes deeply into the complexities of how those come about and what they mean. This takes us to a consideration of quality in terms of regulation and inspection. One view would be that regulation and inspection are in place solely to monitor policies and directives, but another is that regulation and inspection act in the interests of children and offer a clear basis for improvement. This perspective exposes even more debate about the way in which quality is seen and regulated (Jones, 2010). It is unlikely that many would reject the importance of employment law, anti-discriminatory legislation, health and safety, data collection regulations, legislation regarding special educational needs, safeguarding, child protection, or a duty of care. As to whether these directly act upon quality or are an ingredient of promoting quality is again part of an ongoing debate.

It is impossible to ignore the value placed upon implementing regulations and therefore we have to take into account practitioner training and professional development based upon the premise that this leads to increased expertise. Consequently, the whole notion of professional quality encompasses the very nature of professionalism and new professional roles. Engaging in reflective practice and professional development, as well as being proactive to changes in management and leadership approaches, is an essential part of early years practice. In striving to represent quality in practice the following questions acknowledge the need for personal reflection in ongoing professional practice:

- Which learning and teaching approaches are most beneficial to children?

- How do we recognise the important role of the adult in children’s lives?

- Is one view of quality better than another?

There are no easy answers, only varied and different perspectives, but what we can say is there are some common features that represent the foundations of quality provision. They should not be seen as criteria that have to be met or judged in order to be given an award of ‘quality’; rather they should stimulate debate and ask practitioners to think about their relevance in a world that is constantly changing. These common features require practitioners to engage in the debate about quality, to agree or disagree, change and modify, but importantly to reflect on the very idea of what is meant by quality. They can be listed as follows:

- Being a child is a very important part of life and something to cherish. It should not be seen solely as a preparation for the future.

- The environment interacts with the child so is itself something that promotes learning.

- Each child is unique, with individual ways of learning.

- Seeing the child as a ‘whole child’, where learning is holistic and interrelated.

- The young child does not separate experiences into different compartments.

- How a child learns is as important as what they are learning.

- Curriculum frameworks are just that – frameworks.

- Learning how to learn encourages children’s self-direction, where all learning contexts, both formal and informal, are important.

- The environment should contain ‘favourable conditions’ for growing, learning, experimenting, listening and speaking.

- Providing opportunities for learning is as important ...