- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Work with Substance Users

About this book

This book offers a new approach to help students to understand problematic substance use across a range of social work practice settings. Written from both an anti-discriminatory and evidence-based perspective, the book highlights successful responses to the issues. Each chapter includes reflective exercises and examples of further reading, challenging students to critically reflect on their practice.

The book provides a detailed understanding of:

" Historical and current policy relating to prohibition and drug use

" A range of substances and their potential effects on service users

" Models of best practice including screening and assessment, brief intervention, motivation approaches and relapse prevention

" Particular issues and needs of a diverse range of service user groups

This will be an essential text for social work students taking courses in substance use and addiction. It will also be valuable reading for qualified social workers and students taking related courses across the health and social care field.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Historical and Contemporary Context

Part 1 of this book sets the scene for anti-discriminatory social work practice with people who may use substances problematically. The first chapter, ‘A social history of problematic substance use’, provides a brief history of substance use prior to prohibition and regulation, describing how substances and users of them were first medicalised and then criminalised. In this historical light the chapter then describes more recent policy and legislation related to alcohol and drug use, outlines some of the language used to describe problematic substance use, and covers some of the main theories and models that may help us to understand problematic substance use. Chapter 2, ‘Anti-discriminatory/anti-oppressive practice and partnership working’, focuses on the main components of working in an anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive way with service users who may have problematic substance use. The importance of social workers working in partnership and collaboration with substance misuse specialists, including service users and peer support services is also covered in this chapter. Chapter 3, ‘Substances and their effects’, concludes Part 1 by covering some of the main types of substances that are used problematically, their effects and dependence potential.

1

A Social History of Problematic Substance Use

Social workers require knowledge and understanding of the socio-political and historical context of the issues with which they work. In order to understand why we meet with individuals, families, groups and/or communities we must understand not only their personal stories but the context and nature of the issues that they bring. In this way then it is important for social workers to understand some of the history of substances, their use and the political and socio-cultural factors that led to their prohibition or strict regulation. It is important to understand this history as it helps to explain why users of substances are often portrayed negatively, and why people who may have problematic substance use are marginalised and criminalised. To truly understand the nature of the problem or perceived problem provides an anti-oppressive footing, which should be at the heart of all social work practice.

The normalisation of substance use

‘Attempts to govern morals pervade the history of human societies’ (Rimke and Hunt, 2002: 60). Around the world society’s attempt to govern the use of substances has been profound, but it has not always been this way. Substance use for many centuries was seen as a religious experience, as providing creative inspiration, self-medication and/or recreation, with little or no moral condemnation or social control (Bennett and Holloway, 2005). Medicinal use of cannabis in China and the chewing of coca leaves for energy and strength in South America have been documented as dating back several thousand years (Bennett and Holloway, 2005). Throughout history, the use of alcohol, cocaine and opium was unexceptional among people of all classes and backgrounds, including great poets, writers, artists and medical professionals and until the 1960s most known ‘addicts’ in Britain were ‘professionals’ (doctors, dentists and pharmacists) who had direct access to morphine and other substances (Bennett and Holloway, 2005; Davenport-Hines, 2004). In the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century, Britain had a well-established lay and commercial opium trade primarily with Turkey and imported stocks of opium and associated paraphernalia, that was distributed throughout pharmacies and grocers around the country (Strang and Gossop, 2005). Alcohol has played and continues to play an important role in many civilisations around the world (Lloyd, 2010). Britain in particular has a long proud history of making ales and beer and over the course of history alcohol use and indeed drunkenness among all classes has not been uncommon.

The use of substances throughout history was normal, and there was very little if any moral judgement of it. It was only later that health and social concerns leading to medicalisation and then a criminalisation of substance use transpired.

Health and social concerns

In London in the early to late 1700s, the concern regarding drinking, and specifically drinking gin, became known as the ‘gin epidemic’. Gin was known as ‘mother’s ruin’ and the ‘demon drink’ and was blamed for social unrest and absenteeism among the working classes. It is argued by some, however, that in reality gin was merely a concomitant factor in these issues alongside overcrowding and poverty (Abel, 2001). Health concerns regarding alcohol use were officially published by American Benjamin Rush in 1790, when he released An Inquiry into the Effects of Spirituous Liquors on the Human Body and the Mind, more commonly known as the ‘Moral Thermometer’. The thermometer provided a visual depiction of the ‘horrors’ of drunkenness and was later used to support the temperance movement.

Concerns about other substances were also raised when health and social problems relating to their use also started to surface. Alongside public drunkenness and absenteeism, accidental overdosing was quite common. Had it not been for the fact that these health and social problems began to impact on economic productivity, the ‘ruling classes’ may not have cared about the impact substance use was having on the working classes. Abel (2001) argues that the ruling classes strongly endorsed ‘poverty theory’ at this time, the premise of this theory being that the working classes needed to be paid little and kept in poverty so that exports remained competitive. This also kept commodities out of their reach, which in turn meant that they had to work hard to survive, which further supported the continuation of the class system.

In line with poverty theory and over concern about decreased productivity, the ‘ruling classes’ argued that substances and those who used them needed controlling; that individual conduct should be governed in the interests of the nation (Rimke and Hunt, 2002). So began the inextricable link between the use of substances and wider social and cultural concerns and a campaign that would eventually see many substances prohibited or highly regulated (Mold, 2007):

The respectable classes experienced deep apprehensions about the declining hegemony of the traditional authority of the social, political and religious establishments. They responded with a disparate array of projects of moral regulation. (Rimke and Hunt, 2002: 66)

The medicalisation of substance use

Following Benjamin Rush’s earlier work on the ‘moral thermometer’ and during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the medical profession was beginning to theorise about substance use, associated health problems and ‘addiction’. The term ‘addiction’ first emerged in the nineteenth century as an explanation for the overwhelming desire to use alcohol (Mold, 2007). While addiction was initially seen as a disease caused by the consumption of alcohol, the concept soon began to be located in the ‘alcoholic’ rather than the alcohol itself (Mold, 2007). An alliance in the form of the ‘social and moral hygiene’ movement soon formed from the moral codes rooted in religious views and that of the ‘new’ medical institution (Rimke and Hunt, 2002: 61). Medical professionals began to refer to ‘addiction’ as a moral pathology, which saw those who were ‘addicted’ as having an ‘impaired moral faculty’ (Mold, 2007: 2). ‘History can provide numerous examples of how the application of scientific knowledge to a “problem” such as drug use is not value free: but socially and culturally shaped’ (Mold, 2007: 6).

So, while the use of substances began to be prohibited and restricted due to the real and perceived health and social problems they created, the users of the substances themselves also began to be vilified. The association between the use of substances, immorality and disease had begun.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, doctors favoured a combination of medical treatment and ‘moral enlightenment’ in order to treat the ‘disease’ of ‘addiction’, and the medical profession had control over this treatment (Bennett and Holloway, 2005). The 1920 Dangerous Drugs Act permitted doctors to prescribe ‘dangerous’ drugs even to known ‘addicts’ if it was deemed medically necessary. This medical approach is often called the ‘British System’ and was unique to Britain at a time when America was demanding complete prohibition around the world. The ‘British System’ evolved with the publication of the Rolleston Committee Report in 1926. This report supported the continuation of this prescribing strategy, reaffirming the ‘disease’ model of ‘addiction’ and placing the responsibility for the treatment of ‘addiction’ with medical professionals (Bennett and Holloway, 2005; Strang and Gossop, 2005). It was argued that this decision to ‘medicalise’ the problem rather than ‘criminalise’ it at this stage, which was different to other countries (including America), was due to the fact that Britain had at this time in reality only a small problem with the use of drugs (Bennett and Holloway, 2005).

The criminalisation of drug use

While the medical profession was still the dominant force in the treatment of ‘addiction’, in the early 1900s the British government began to take more of an interest in ‘drug addiction’. It was at this time that thinking about the crimi-nalisation of substance users began. For the same reasons that drug use was medicalised, drug users slowly began to be criminalised.

Opium use amongst the working class was thought to be damaging to morality and detrimental to production, echoing elements of the temperance movement’s attack on alcohol. (Mold, 2007: 3)

The Opium Convention, signed by 12 nations at The Hague in 1912, proposed among other things the closing down of opium dens and that the possession and sale of opiates (morphine, opium and heroin) to unauthorised persons should be punishable by law (Bennett and Holloway, 2005). Following the signing of the Opium Convention, the British Home Office began to take responsibility for matters relating to dangerous drugs (in June 1916). This included a focus on international distribution and consumption.

The Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920, while placing the prescribing of drugs in the hands of the doctors, prohibited the importation of raw opium, morphine and cocaine, and allowed the Home Office to regulate the manufacturing, sale and distribution of dangerous drugs (Bennett and Holloway, 2005). This appeared to mark the beginning of the criminalisation of drug use in Britain, and ratified the principles of an even earlier Defence of Realm regulation that came into force in 1915, that was concerned with the use of drugs by the British armed forces in the First World War. Britain made cannabis illegal in 1928 as it had been previously omitted from the Dangerous Drugs Act.

Following the introduction of these policies, substance use and the number of known ‘addicts’ remained relatively low and constant in Britain until the 1960s. The 1960s, however, saw a marked increase in the use of drugs by a wide range of people from all social backgrounds. This increase in the use of what were now ‘illegal’ substances appears to have come about due to younger people having more personal income, more movement of people and substances around the world and the sixties culture encompassing ‘freedom’ and the importance of spiritual experiences. The use of heroin registered the biggest rise at this time, but cannabis and cocaine were also regularly used, especially in London’s ‘music scene’. At this time, some of the powers that medical professionals had enjoyed under the ‘British System’ began to be limited by the Home Office. It was thought at the time that the marked increase in drug use that was being seen was as a result of over-prescribing by a small number of doctors. Following this ‘explosion’ in the use of substances, there was a perceived need to regulate further and criminalise the use of drugs.

Drug policy and legislation

The 1960s

The Interdepartmental Committee on Drug Addiction, chaired by Sir Russell Brain (the First Brain Report), reinforced the findings of the earlier 1926 Rolleston Report and favoured the continued use of drug prescription for ‘addicts’ where necessary, and emphasised the relatively minor scale of drug use in the UK. While this report was widely criticised at the time for not recognising the changing drug-using culture in the UK, the media had begun to pick up on these changes. It was at this time that sensationalist reporting of the dangers of the ‘drug epidemic’ began.

The 1961 UN drugs convention, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, marked a key turning point in global prohibition, safeguarding prohibition in domestic law around the world, and closing down any possibility of regulated models of the production and supply of illicit drugs (paradoxically, alcohol and tobacco were excluded) being introduced by individual countries. The Brain Committee was reconvened in 1964 following pressure from the media and the public. While this report (the Second Brain Report) was more realistic, it is said to have focused too narrowly on the London scene and neglected other parts of the UK, where drug use culture was also changing (Yates, 2002).

The UN Drugs Convention and the Second Brain Report informed the implementation of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1967, which effectively saw the beginning of the end of the ‘British System’ of opiate prescribing. The Dangerous Drugs Act introduced the notification of ‘addicts’, wide-ranging restrictions on the prescribing rights of doctors, and the establishment of special treatment centres or clinics for the provision of drug treatment (Drug Dependency Units or DDUs). The right to prescribe heroin and cocaine to ‘addicts’ was now limited to specialist psychiatrists working in these clinics and equipped with a licence from the Home Office (Lart, 2006). The quantity of these drugs that was prescribed was also dramatically reduced, with the heroin substitute methadone often being supplied in their place (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2009). The limitations placed on the prescribing of opiates and cocaine by the Dangerous Drugs Act 1967 came at a time when the black market for drugs was becoming established, especially in London. Whether or not this new legislation caused the black market, or was in response to the beginnings of it, is arguable, but what was clear was that the number of drug users continued to increase through the 1960s and well into the 1970s (Yates, 2002).

The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971

The 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 established the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD). ACMD was set up to advise the government about drug misuse prevention, and how to deal with social problems related to drug misuse (Yates, 2002). The Misuse of Drugs Act also implemented the ‘schedule’ system in accordance with the judgement of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs as to the potential for abuse and the therapeutic value of each drug. These schedules govern possession and supply of drugs controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act as well as prescribing, safe custody, importation, exportation, production and record keeping. These criteria still underpin UK drug policy today. Under the Misuse of Drugs Act it is an offence to possess a controlled substance unlawfully; possess a controlled substance with intent to supply it; supply or offer to supply a controlled drug (even if it is given away for free); or allow a house, flat or office to be used by people taking drugs.

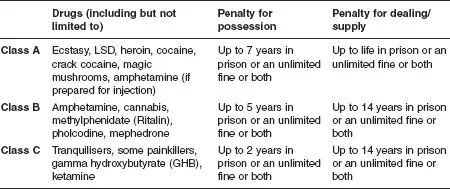

Table 1.1 Drug classification under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971

Source: Home Office, 2009a

Drugs are scheduled as either class A, B or C according to how damaging they are thought to be to individuals and communities. The different classes carry different penalties for possession and supply. A simple table (Table 1.1) is presented that helps to make sense of these classes.

All of the drugs identified in this schedule under the Misuse of Drugs Act are considered to be controlled substances and are illegal to use, except where they have been prescribed. Class A drugs are those that are thought to be the most dangerous to individuals, families and communities, while Class C drugs are thought to be the least harmful.

This scheduling system...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PRAISE FOR THE BOOK

- INTRODUCTION

- PART 1 Historical and Contemporary Context

- PART 2 Diverse Populations

- PART 3 Concepts and Models for Social Work Practice

- PART 4 Social Work Practice Settings

- CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX A1

- APPENDIX A2

- APPENDIX B

- APPENDIX C

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Social Work with Substance Users by Anna Nelson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Trabajo social. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.