![]()

1 What RCTs Can and Cannot Tell Us

Introduction

One of the issues which has faced education policy over much of the last century is the pace of change. A range of different educational interventions continues to come and go. Fashions and fads within education are rife and while most may have some common-sense appeal, many have little evidence supporting them as effective pedagogical practices. While most people working in the field of education have good intentions, there remains a lack of robust evidence on the range of different pedagogical practices and whether they are actually effective in improving learning and skills among all or different subsets of learners.

RCTs within education offer the possibility of developing a cumulative body of knowledge and an evidence base around the effectiveness of different practices, programmes and policies. However, and as touched upon in the last chapter, their use remains controversial and they have not been widely accepted among the educational research community. The educational and wider social science research community within the UK has remained largely sceptical of such experimental approaches, which are often defined as part of a positivist paradigm and linked with a neo-liberal audit culture within policy. This, however, has not prevented a number of prominent advocates from arguing for the greater use of trials drawing on the model within medicine and the health sciences (Fitz-Gibbon, 1996; Hargreaves, 1996; Oakley, 2000, Torgerson and Torgerson, 2001) which has, in turn, stimulated considerable debate surrounding the use of randomised control trials in educational settings over the last decade.

In this chapter we explore some of these debates about the methodological, philosophical, ethical and political issues associated with conducting RCTs in education. We critically reflect on the literature and also draw upon our own experience of conducting trials. We aim to set out an approach to trials informed by a critical realist perspective and one that is post-positivist in outlook. In doing so, we hope to convince some of those sitting on the sidelines of the merits of such an approach to evaluation research, whilst also tempering the calls that have been made by those who would advocate an over-scientific approach.

Pedagogical practice and experimentation in schools

Education as a profession has not had strong links with research. Much of what is taught in classrooms is rooted in tradition, experiential knowledge, expert opinion, or directed through central or local policy perspectives (Hargreaves, 1996). Moreover, teaching practice by its nature is often experimental and the profession often buys into new ideas with vigour. New educational interventions, policies and practices are regularly introduced within schools. In fact, schools continually experiment with different programmes and approaches. However, there is rarely any systematic attempt to evaluate their impact on pupil learning or other outcomes, beyond teacher intuition. Few of these practices, which are often targeted at the most disadvantaged pupils, have been rigorously assessed in a systematic way against the proposed outcomes that they intended to change. As such, educational practice remains vulnerable to fads. Some of the fads which have entered the classroom include left and right brain training and placing a bracelet on the wrist, learning styles, avoiding food additives, whole language approaches, the new maths and open classrooms to name a few (Goldacre, 2013). More worrying still is that, without a robust evidence base, many of the various fashions introduced in schools are ones that had already been abandoned in the past as ineffective novelties, but have now come around again with a new generation of teachers or policymakers (Raffe and Spours, 2007). Whilst innovation is therefore at the heart of the teaching profession, there is a tendency for this to take place in the dark and thus for the constant recycling and reintroduction of fads, with little sense of learning or progression.

In this sense, RCTs have a critical role to play in supporting the natural experimentation and creativity that take place in schools and classrooms all the time. In particular, and as Campbell and Stanley (1963: 2) argued over fifty years ago: ‘[the experiment] is the only means for settling disputes regarding educational practice, as the only way of verifying educational improvements, and as the only way of establishing a cumulative tradition in which improvements can be introduced without the danger of a faddish discord of old wisdom in favour of inferior novelties’. What RCTs offer, therefore, is not just the opportunity to provide robust evidence relating to whether a particular programme is effective or not, but also – and over time – the creation of a wider evidence base that allows for not only a comparison of the effectiveness of one programme or educational approach against another but also for how well any particular programme works in specific contexts and for differing sub-groups of learners. Moreover, we would suggest that there is also a moral imperative to rigorously test programmes, not just so that we can ensure that we are making the best use of the limited resources that are available but also to make certain that we are neither holding learners back by persisting with an approach that is simply ineffective nor, critically, that we are not actually exposing them to potentially harmful effects.

One classic example of the dangers of fads in education, and the importance of developing a robust evidence base, is the Scared Straight programme designed to ‘scare’ or deter at-risk or delinquent children and young people from a future life of crime (Petrosino et al., 2013). The programme was introduced by a number of inmates serving life sentences in a New Jersey (USA) prison and involved juveniles visiting the prison and being subject to an aggressive presentation by the inmates on life in prison. A television documentary on the programme was broadcast in 1979 and showed the inmates shocking the juveniles with stories of rape and murder in prison. The documentary also claimed that the programme was successful in the fact that 16 of the 17 delinquents featured in the documentary did not engage in further offending for the next three months – ‘a 94% success rate’. Not surprisingly, the programme received considerable media attention and became the latest fad that promised to offer a simple (and cheap) silver bullet in relation to crime prevention. Very quickly, the programme was rolled out in over 30 states across the USA (Petrosino et al., 2013).

However, and by 1982, the first RCT of the New Jersey programme was published reporting that it had found no evidence of an effect on the offending behaviour of participating juveniles in comparison with a control group (Finckenauer, 1982). Indeed, the study reported that those who participated in the programme were actually more likely to be arrested subsequently. Further trials later emerged that also reported similar worrying findings, and in 2003 a research team undertook a full systematic review of the international evidence to date in relation to this programme, conducted through the Campbell Collaboration. This review, updated in 2013, found nine RCTs that had been conducted to date on Scared Straight and similar programmes in eight different US states (Petrosino et al., 2013). The authors of the systematic review were able to combine the data from seven of these in order to conduct what is termed a meta-analysis. In analysing the pooled data, the authors found that, overall, there was clear evidence that participation on the Scared Straight and similar programmes actually increased the odds of juveniles re-offending by between 1.6 and 1.7 to 1. In other words, the odds of juveniles re-offending had increased by between 60 and 70% amongst those who had participated in the programme compared to a control group.

Thus, while having much intuitive appeal, the use of shock tactics in this case was not only found to be ineffective but also the growing body of evidence presented a consistent picture that it actually exacerbated the problem. This is a particularly clear example of the role that RCTs can play in helping us guard against the tendency to be taken in by the latest fads that, on the surface, look as if they should work and that are also often extremely appealing precisely because they present simple and cheap solutions to what are complex underlying problems. In many cases, the findings from RCTs might not be as stark as these found for the Scared Straight programme. For many school-based education programmes it may be that they are just ineffective rather than having a negative effect. However, the implications are no less serious given the direct investment that is required to deliver many programmes, not to mention the often substantial opportunity costs associated with schools and teachers putting their time and efforts into delivering a programme that does not work at the expense of one that does. What we have with RCTs is the promise of not just testing whether a specific programme or intervention works in a particular context, but also the broader goal of building and maintaining a robust evidence base enabling us to understand the relative effectiveness of differing approaches and, within this, which approaches might be most suited for which particular contexts.

Paradigm wars and the critique of RCTs

Randomised trials have a long history in educational research, with Oakley (2000) tracing their use back to the 1920s and noting that the early trials in education predated their use within medicine. While a natural science approach associated with a logical positivist philosophy of science held sway within educational research throughout the 1950s and 1960s, it came under increasing attack from interpretivist and feminist challenges, especially following the publication of Thomas Kuhn’s (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Kuhn’s notion of paradigm shifts provided a framework for understanding science not as a linear and objective process characterised by the gradual growth in knowledge, but as a socially constructed process where the dominant paradigm at any one time tends to determine and define what theories, methods and ways of interacting are considered appropriate and often regarded as natural and unproblematic. This, in turn, allowed for existing scientific approaches, most notably the various strands of positivism held together with a belief in an objective and value-free social science, to be effectively challenged.

As a result, interpretivist approaches increasingly came to critique the dominance of positivist research models based on quantification and applying a natural science model to educational and social research from the 1970s (Pring, 2015). Over the years these interpretivist approaches have developed and diversified, and have played a critical role in stressing the importance of qualitative research and the need to appreciate and situate individuals’ experiences and perspectives in order to better understand human behaviour and interaction. Whilst initially adopting a realist approach, in recognising the real existence of a social and physical world, many of these perspectives have become more idealist as social constructivist and post-modern perspectives have largely taken hold. Increasingly many of these approaches have questioned the very possibility of knowledge beyond relativistic multiple perspectives. These interpretivist approaches have typically positioned themselves firmly against, and in opposition to, methods rooted in a positivist tradition. Moreover, such debates have resulted not only in the growing dominance of qualitative approaches in educational research, but also an inbuilt scepticism of the value of quantitative methods. It is in this space that the role of experimental methods, and the use of RCTs in particular, has become situated.

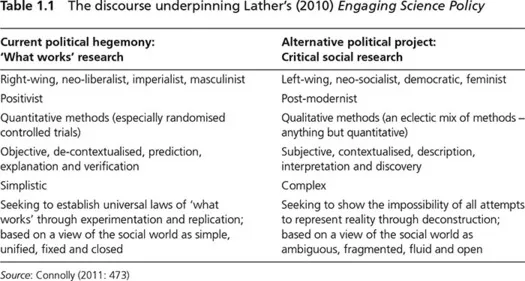

Unfortunately, and for many in the educational research community, RCTs would appear to symbolise the old positivist tradition and to represent an existential threat to the large body of work that now exists, located broadly in the interpretivist tradition and later developments in post-modern and post-humanist perspectives. A brief taste of the nature of this opposition to RCTs, and its embeddedness in educational research, was provided in the last chapter through the extracts from one of the dominant methodology textbooks in education (Cohen et al., 2011). However, and particularly over the last decade, this opposition has increased through the emergence of a strong discourse underpinning this resistance to RCTs. It is a discourse that has tended to create two binary and opposing subject positions: one organised around what has been regarded as the current political hegemony associated with ‘what works’ and the wider evidence-based practice agenda; and the other representing an alternative political project, based broadly upon critical social research. A clear example of this discourse can be found in the book by Lather (2010), Engaging Science Policy, that provides a critique of the move towards a ‘what works’ agenda in government policy and research funding in a number of countries, including most notably the USA and the UK. The discourse underpinning her book is summarised in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1Engaging Science Policy Source: Connolly (2011: 473)

For Lather (2010) this ‘what works’ agenda has become increasingly apparent in the USA since 2001 and the passing of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act by the new Bush Administration that represented the most wide-ranging reform of the education system in the USA since 1965. One of the key underlying themes of NCLB has been the promotion of a culture of accountability through a focus on setting high standards and measurable goals. Within this, the promotion of ‘scientifically based research’ has come to be one of the main drivers of this reform, with a clear emphasis on RCTs as providing the mechanism for determining which educational programmes are leading to measurable improvements in outcomes for learners and thus providing the basis for future funding decisions by federal government. These developments, in turn, have led to a significant increase in funding for RCTs compared to other forms of research and this has been taken forward by the Institute of Education Sciences, formed in 2002 within the US Department of Education, with the mission to ‘provide rigorous evidence on which to ground education practice and policy’.

Such developments have been paralleled in the UK with the emphasis placed on evidence-based policy and practice by the incoming New Labour government in 1997. As made clear in the Labour Party Election Manifesto of that year: ‘New Labour is a party of ideas and ideals but not of outdated ideology. What counts is what works. The objectives are radical. The means will be modern’ (quoted in Oancea and Pring, 2009: 12–13, emphasis added). This emphasis has been taken forward through successive Labour administrations and the following Conservative/Liberal Democrat Coalition Government of 2011–15. The most recent and significant manifestation of this focus has been the establishment of the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) in England in 2011 by the Sutton Trust, with a founding grant of £125m from the Department for Education. As an independent organisation, the EEF seeks to play a key role in identifying and funding innovative programmes and interventions in education that address the needs of disadvantaged school-aged children in England. It has set itself the goal of securing additional investments to enable it to award as much as £200m in supporting the development, delivery and rigorous evaluation of programmes over its fifteen-year lifespan. In its most recent Annual Report for 2015–16, and within just five years of its formation, the EEF notes that ‘more than £75m has so far been invested by the EEF in supporting 127 programmes [in England]. Collectively, these have involved close to one-third of all schools – 75,000 schools and nurseries in England – and reached over 750,000 children and young people’ (EEF, 2016: 2).

What these developments have led to, according to Lather (2010), is a new ‘what works’ political hegemony that is associated with, and serves the needs of, right-wing neo-liberal governments; that privileges quantitative methods and in particular RCTs; and that is overly simplistic and positivist in focus. For Lather, what it rules out are alternative forms of (largely qualitative) research that recognise and help us appreciate the complex and subjective nature of the social world and also recognise the multiple and embedded forms of power and inequalities found within this. This creation of two binary opposite positions – of what works research versus critical social research – is made possible in part by what Oakley (2006) describes as the many ‘rhetorical devices’ used to encourage rejection of RCTs by the reader. Such devices were clearly evident in the quotations from Cohen et al. (2011) reproduced in the last chapter, which present RCTs as crude, artificial, laboratory-style experiments that are dependent on the ability to control educational settings as natural scientists would control conditions in their laboratories. These rhetorical devices are unfortunately commonplace. Take, as another example, the following description of RCTs:

Here, all variables are held constant except the one under investigation. Ideally, this one variable is deliberately changed, in two exactly parallel situations as, for example, when a new medical drug is tested against a placebo. If a difference is noted, rigorous tests are conducted to minimize the chances that it is coincidental. Laboratory experiments are repeated, to ensure the results always turn out in the same ways. When involving human populations, inferential statistics are used to determine the probability of a coincidental result. Th...