Secondary Science 11 to 16

A Practical Guide

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

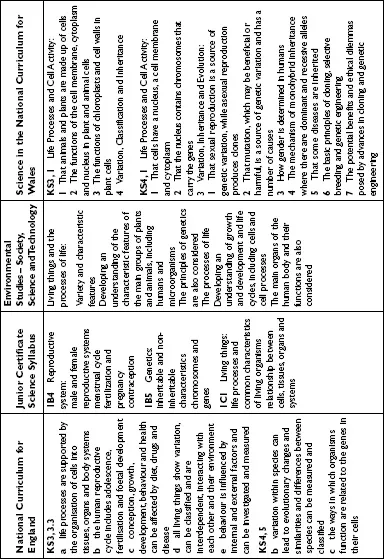

Full of suggestions for exciting practical work to engage children, this book addresses and explains the science behind the experiments, and emphasises the need to engage the learner through minds-on activities. It shows you where to make links to the national curricula in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and it covers the three sciences: chemistry, biology and physics. The detailed subject knowledge helps you grasp key concepts, and there are lots of useful diagrams to illustrate important points.

Experiments include:

- extracting DNA from a kiwi fruit

- capturing rainbows

- the chromatography of sweets

- removing iron from cornflakes

- a plate tectonic jigsaw

These practical activities will provide you with ways to ensure your students respond enthusiastically to science, and the book will also help you develop your subject knowledge and ensure you meet your Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) standards. Perfect reading for Secondary Science PGCE students, as well as those on the Graduate Teacher Programme (GTP), this book is also ideal for non-specialists who are looking for support as they get to grips with the sciences.

Gren Ireson is Professor of Science Education at Nottingham Trent University. Mark Crowley is a Teaching Research Fellow in the Centre for Effective Learning in Science, Nottingham Trent University. Ruth Richards is Subject Strand Leader for the PGCE and Subject Knowledge Enhancement (SKE) courses in Science at Nottingham Trent University, and an examiner for A-level Geology. John Twidle is Subject Leader for the PGCE and MSc Science programmes at Loughborough University.

Information

| Section 1 | Beginnings and development of living things |

- cells – the building blocks of living organisms;

- reproduction – the continuation of life; and

- genetics – the variation and inheritance of characteristics.

- the various functions of animal and plant cells;

- the process of reproduction;

- the process of genetic inheritance; and

- the passing on of characteristics.

| 1 | Looking at life |

- the characteristics of life

- cell structure

- practical techniques for making slides

- levels of organization

- diffusion and osmosis.

Test your own knowledge |

- How do we know something is alive?

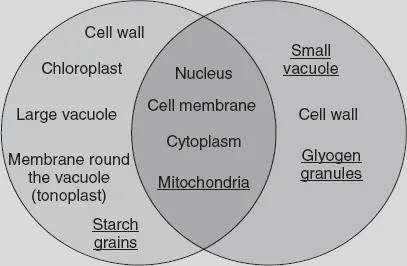

- What is a cell? What are the main components of an animal and a plant cell? Which components are shared by both plant and animal cells?

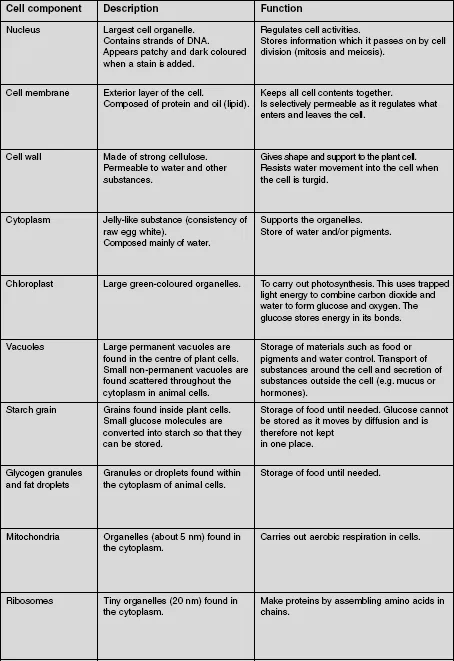

- What is the function of each cell component?

- How do substances get in and out of cells? Are there any rules for this?

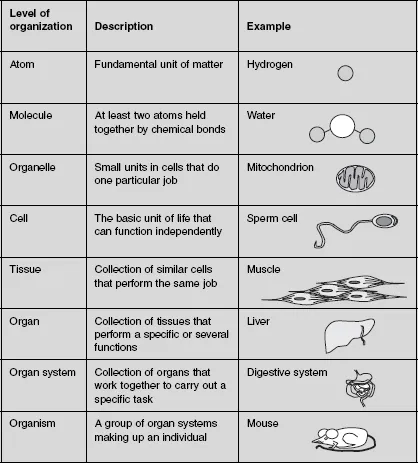

- What is the definition of a cell, an organelle, a tissue and an organism?

What is life?

- Movement: Organisms may move all or parts of their bodies towards or away from influences that are important to them. For example, a plant may move its leaves towards the sun.

- Respiration: The release of energy stored in food, such as glucose, to provide power for the cell to function. The energy currency of the cell is adenosine tri-phosphate, or ATP for short. Respiration takes place in the mitochondria of every cell.

- Sensitivity: Awareness of the organisms’ surroundings. This may be complex, such as the passage of nerve impulses, or simpler, such as the growth of plant roots down into the soil.

- Growth: An increase in size, such as the division of one cell into two identical cells (mitosis).

- Reproduction: The formation of more individuals from one parent (asexually) or two parents (sexually).

- Excretion: Getting rid of the products of the chemical reactions that have taken place in the organism (metabolism). Metabolism occurs at a cellular level, and so excretion includes getting rid of water and carbon dioxide. (Not getting rid of solid waste!)

- Nutrition: Using a food source to release energy for cell function. This is either autotrophic, when plants make their own food by photosynthesis and then metabolise it, or heterotrophic, when ready-made food is taken into an organism.

The cell

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the authors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Section 1 Beginnings and development of living things

- Section 2 Chemical and material properties

- Section 3 Light and motion

- Section 4 The Earth and its place in the universe

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app