- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Acute Illness Management

About this book

The prospect of caring for acutely ill patients has the potential to overwhelm students and newly qualified health professionals, with many reporting feelings of stress, fear and inexperience. In this context, Acute Illness Management arrives as an important and much needed text covering the fundamental aspects of care in the hospital setting.

This book is designed to address the student?s needs by equipping them with a practical understanding of the essential skills ranging from resuscitation to early intervention and to trauma care. It explains the rationale behind the key protocols of care highlighting the relationship between theory and practice.

Key features include:

-Up-to-date legal and ethical content.

-Tips for analysing care decisions in a critical and effective manner, and

-Reflective activities and self-assessment questions to cement learning.

Acute Illness Management is an invaluable resource for students and qualified practitioners in nursing and other health professions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Acute illness management: an overview

Chapter aims

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Define what acute illness is

- Explain how acute illness typically develops in patients

- Identify some deficiencies in how acutely ill patients are recognised and managed

- Describe some potential ways through which acute care can be enhanced

- Review your own practice with regard to acute illness management and identify any learning needs that you may have

Acutely ill individuals can present in all healthcare settings and thus every health professional needs to have the knowledge and skills necessary to respond to this group of patients. In practice, this means that all health professionals must be able to recognise those who are at risk of becoming acutely ill and take early action to stabilise them in order to avert further deterioration.

Defining acute illness

Before going any further with the discussion of acute illness, it is important establish what exactly acute illness is. On reviewing the literature, it is difficult to find one definition of acute illness that would suitably cover all patients in all specialities. What is easy to locate is a definition of the term ‘acute’, which is synonymous with illness that is rapid in onset, severe and short lived. The term ‘acute illness’ therefore describes patients who have rapidly become ill with a severe condition that may be life-threatening, with a degree of reversibility to it.

The inclusion of the term ‘rapid’ can be a little confusing as it conjures images of sudden collapse and as such requires further clarification. There is evidence that patients who suffer cardiac arrest have significant changes in their clinical observations for up to 24 hours before the cardiac arrest occurs (Hodgetts et al., 2002). This suggests that for many patients there is a period of acute illness that precedes the cardiac arrest. In this context, the term rapid therefore encompasses a gradual and insidious decline that occurs progressively over hours as opposed to weeks. While cardiac arrest, defined by the cessation of breathing and absence of cardiac output, represents an end point in this decline, there is a significant window of opportunity to intervene prior to arriving at this critical end point, which potentially allows cardiac arrest to be averted in some patients and morbidity reduced in others.

It should then be possible to define this time period of acute illness that precedes many cardiac arrests. To describe this phase of illness, where the patient is maximally physiologically disarranged, I shall use the term acute life-threatening event (ALTE). While ALTE is more difficult to define than cardiac arrest, it represents a period of time prior to cardiac arrest when a patient requires emergency resuscitation to avert cardiac arrest or other serious complications of an ALTE. The aim of acute illness management is then to detect those who are en route to, or have arrived at, an ALTE and to treat them rapidly and effectively before complications can occur.

Acute illness: a physiological disarrangement

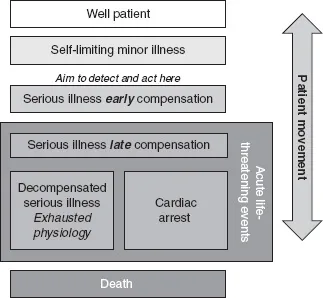

Illness is something that spans a continuum of different clinical states that a patient may find themselves in; Figure 1.1 illustrates the regions of this spectrum. For most patients who become ill, the self-limiting nature of the illness and ability to self-repair confines the illness to the minor illness bracket. For others where the cause of the illness is more serious or the person’s ability to self-repair is limited, they will progress on to the serious illness bracket. When this occurs the body will attempt to compensate for the illness state that has been encountered in an effort to maintain homeostasis. However, the body’s ability to compensate for illness is limited, and illnesses, if severe, can exhaust the compensatory mechanisms of the body and bring about a massive physiological disarrangement. At the same time the activation of the compensatory mechanism places additional demands on an already diseased body and this in itself can further worsen the physiological disarrangement experienced by the patient. In some cases of acute illness it is in fact the body’s own healing mechanism that bring about the illness state.

FIGURE 1.1 The spectrum of acute illness.

As the patient moves along the spectrum, from a point of wellness to a point where they are at risk of death, they will experience mounting physiological disarrangement. The further a patient moves along the spectrum of acute illness, the more difficult it is to correct their ailing physiology and the more likely it is that they will endure heightened morbidity and mortality. The speed at which a patient will progress along this spectrum is dependent on the actual cause of the disease; for some the progression will be quite slow but for others the progression may occur in quick succession with a small minority experiencing a sudden shift from a well patient state to cardiac arrest.

Acute illness is in simple terms a problem with a person’s physiology that interrupts or hinders the factors that would normally regulate homeostasis (Chapter 2). There are many factors that can interfere with homeostasis, and while it is beyond the scope of this text to explore each and every one of the disease processes that can result in acute illness, Chapter 2 will endeavour to explain some most important physiological concepts that underpin the development and management of acute illness. Example causes of acute illness are provided in Box 1.1.

BOX 1.1 Examples of acute illnesses

Airway obstruction, resulting in difficulty in breathing and ultimately hypoxia

- Loss of muscle tone/gag reflex

- Vomit

- Foreign body

- Swelling of the airway

Breathing problems, resulting in hypoxia and possibly acidic blood

- Acute asthma

- Exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Pneumonia

- Carbon monoxide poisoning

- Pneumothorax/plural effusion

Circulatory problems, resulting in shock and possibly acidic blood

- Myocardial infarction

- Heart failure

- Vomiting and diarrhoea causing dehydration, blood loss, other fluid loss

- A problem with the heart’s rhythm (arrhythmia)

Kidney problems (renal failure)

- Too much fluid in the body (hypervolaemia/fluid overload)

- Too little fluid in the body (hypovolaemia)

- Altered electrolyte balance, particularly of sodium, potassium and calcium

- Problems with the regulation of acid in the blood

- Problems with blood pressure (hypertension/hypotension)

- Problems with red blood cell production (anaemia)

Problems with how acute illness is managed

It is now well recognised that acutely ill patients are not always well managed. Indeed a study by McQuillan et al. (1998) demonstrated that poor quality acute care not only occurred, but also that where patients were subjected to poor quality care either by not being recognised as acutely ill soon enough or not being managed correctly that there was a dramatic worsening in a patient’s chances of surviving the episode. McQuillan et al. (1998) discovered that patients were approximately 20% more likely to die when they were the recipients of poor quality care prior to intensive care unit (ITU) admission. Hodgetts et al. (2002) also demonstrated that an estimated 23,000 otherwise preventable in-hospital cardiac arrests occur in the UK each year as a result of poor quality acute care. These both shocking and saddening statistics are made worse when one considers that most of the variables that lead to poor patient outcomes relate to basic facets of care such as appropriately interpreting nursing observations, maintaining an adequate fluid balance, providing tailored oxygen therapy and maintaining a patient’s airway and breathing (National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2005).

While the picture that has thus far been painted of the state of acute illness management is quite a dismal one, a positive point to bear in mind is that many of the failings are readily reversible. This sets forth a challenge for health professionals to identify areas of poor practice and put in place plans to correct it.

Improving the response to the acutely ill

Several strategies have been proposed to improve the response to the acutely ill. These have included the use of early warning scores (EWS), early goal-directed therapies and improved education for those charged with responsibility for detecting acute illness and managing it. Following the development of EWS systems (Morgan et al., 1997; Stubbe et al., 2001) the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence issued guidelines on how to monitor people who are acutely ill and how to act once deterioration has been detected (NICE, 2007). These guidelines advocate the use of EWS systems for patients cared for in hospital.

EWS systems are essentially decision support tools which allow the identification of those who are at risk of deterioration. Most do this by setting reference ranges for physiological observations that are usually taken in the clinical environment. When these observations deviate from the reference range, a score is applied. When the score reaches a certain threshold, a specific action is required as dictated by local protocols. The 2007 NICE guidance on the acutely ill in hospital recommends that the scores generated by EWS are classified as either low, medium or high and the clinical response that a patient receives is directed by this classification. These classifications are set locally and will vary according to the EWS tool used, of which there are many, with different thresholds for action set by local advisors. This potentially introduces an inequality, as patients seen in different hospitals may be classified differently even when they present with clinically identical observations. To combat this situation, the Royal College of Physicians proposed the development of an NHS early warning score, to be known as the NEW score (RCP, 2007). Indeed Prytherch et al. (2010) have recently developed and validated a scoring system that holds significant promise to standardise EWS.

While EWS systems play an important role and act as an enhancement to previous practice, their use is only a small part of the answer to the problems surrounding the care of the acutely ill. As with all protocols, they are designed to be used by thinking people. To illustrate the importance of thought, consider the observations listed and try to answer the questions i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication and thanks

- About the author

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Acute illness management: an overview

- 2 The physiology of acute illness

- 3 Patient stability assessment

- 4 Problems with the airway and breathing

- 5 Understanding and resolving problems with the circulation

- 6 Electrocardiographic monitoring

- 7 Responding to the acutely ill patient

- 8 Significant others, breaking bad news

- 9 Legal, ethical and professional issues

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Acute Illness Management by Chris Mulryan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nursing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.