![]()

Strand 1

Exploring identities

![]()

1 | Equality and difference in the Early Years |

| | Alison Street |

This chapter will consider why equality of opportunity is important in Early Years provision. It will explore the concept of difference, both as a resource for learning and as a way of aiming for equitable practice.

By the end of this chapter you should have:

- considered the difference between equality and equity in relation to early childhood education;

- reflected on how inequalities in health and well-being can impact on children’s sense of self and educational opportunities;

- thought about ways that disagreement can be a positive force for change in relation to diversity;

- considered how young children and their parents are involved in decisions about education and care.

Introduction

Inequality is now seen as the norm, regardless of how much harm it does to our shared humanity.

(Simon Callow, 2012)

In the statement above, Callow was referring to a celebration of inherited wealth through the royal 2012 Diamond Jubilee, but thereby recalling the much older meaning of a jubilee; the ancient Hebrew tradition of rebalancing rights of property, land ownership and wealth to create a more equal distribution across society. Whether you have monarchist or republican sympathies is not the debate in this chapter. But the need for redistribution of wealth is one of the emerging themes for discussion. This chapter will focus on questions for early childhood education and care that rise from considering the inequality of the socio-economic and cultural contexts in which provision is situated. Inequality has become more evident because in the second decade of the twenty-first century, publicly available data has become increasingly accessible on the social determinants of health and lifestyle. These relate both to the UK, such as the subsequent analysis of data from the 1970 cohort of children (Feinstein, 2003), and across the social hierarchies in a global context, such as researched by Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) in their book The Spirit Level. The latter both exposes and explains why inequality is a significant factor that influences both the structures in which people live and work, but also in how adults bring up young children and make decisions about their learning. It will be argued that early childhood is not immune and its settings cannot be protected from prevailing political and economic conditions, as these influence such everyday preoccupations as the cost of childcare, accessibility of information and support for parents, amount of parental leave at birth and availability, or lack of, parental choice.

There is not room in this space to interrogate the range of sociological, economic and political issues that impact on early childhood, and solutions are not sought. Rather, what follows is a discussion on themes emerging from two extracts that raise questions about both why and how unequal conditions and structures can influence young children’s lives. In as much as family contexts, culture, ethnicity, class and gender impact on young children’s developing identities and sense of belonging, there is a strong overlap with Chapter 3 in its focus on inclusive practice. The first part of the chapter will centre on the findings and recommendations of the Marmot Review team (2010) in Fair Society, Healthy Lives. This emphasises the links between socio-economic background, health inequalities and developmental outcomes for children in the UK. The second extract, from Michel Vandenbroeck’s editorial Let us disagree (2009) explores the necessary move early childhood education has made away from an ‘equalising’ strategy towards diversity in approach, when confronting decisions about difference in families’ social, physical and cultural backgrounds and beliefs. The two extracts appear to hold the view in common, that both investment in the earliest years, and also a striving to understand what underlies inequalities, are imperative for the future balance of society and for people to live harmoniously together.

Health matters

Even though the UK is generally considered to be wealthy, with universal access to healthcare free at the point of delivery, there have been numerous changes to the National Health Service in the last twenty years, including increasingly politically target-driven goals. Through a new act in 2012, the decision making on how services for patient care are commissioned has been devolved to groups led by medical general practitioners (GPs) in a Coalition policy move to reduce overall spending on public services. Simultaneously, there has been an expansion in health awareness from a global perspective, in availability of health promotion, and preventive measures for eradicating disease. One important measurement for the health of a nation is infant mortality rates. Increased prosperity in the UK led to a reduction in infant mortality from 6 to 5 per 1,000 live births, and under-5 mortality from 7 to 6 per 1,000 live births over the ten years from 1996 to 2006 (UNICEF, 1996, 2005). The long-term trend has been downwards; however, the gaps remain, both in infant mortality and male/female life expectancy between routine and manual workers and those in joint or registered partnerships (Marmot Review, 2010, 45).

Underdown (2007, ch. 4) expands on health inequalities in early childhood, drawing attention to the differences between children growing up poor in a poor country where they may lack access to clean water, sanitation, adequate nutrition and healthcare, and be vulnerable to diseases, often water-borne, with children growing up poor in a rich country, where definitions of relative poverty are not fixed. She claims that despite improvements in living conditions, general hygiene and immunisation programmes there are new threats to child health from social living conditions. These include child obesity, a reduction in many poorer urban areas of safe places to play outside, emotional and behavioural difficulties arising from breakdown in relationships and from children witnessing domestic violence, from childhood injury and smoking. Silberfield’s (2007, p58) helpful commentary that raised questions about strategies needed to nurture a strong and healthy child, corroborated the relationship between inequality and a rise in young children’s mental health problems; that conditions such as anxiety, eating disorders and depression are linked with poverty, inequality and deprivation. Children in families who experience homelessness or temporary accommodation or who have suffered as a result of conflict, such as refugees or asylum seekers, are also likely to have higher incidences of mental health problems (BMA, 2006).

The unequal chances that young children get because of their socio-economic contexts are clearly set out in the Marmot review, which was researched by nine task groups, involved scores of researchers and gathered qualitative evidence from professionals in health, involving discussion with stakeholders, focus groups and working committees. It admits inequalities in health are not a new phenomenon; there have been examples during the last two hundred years of ways seeking to address them, and that the motives behind the review may be ideological, but the recommendations are based on evidence which cannot be ignored for the sake of future society.

health inequalities that could be avoided by reasonable means are unfair. Putting them right is a matter of social justice. But the evidence matters. Good intentions are not enough.

(Marmot et al., 2010, p3)

The increasing evidence available in the public domain since records began in 1961 inform Wilkinson and Pickett (2010, p247) in the same argument:

The advantage of the growing body of evidence of the harm inflicted by inequality is that it turns what were purely personal intuitions into publicly demonstrable facts.

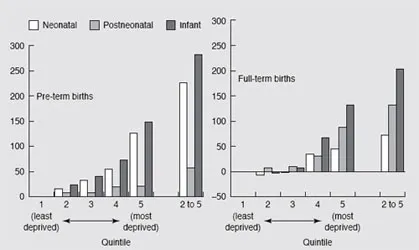

As you read the following extract from Chapter 2 of the Marmot Review, you will find links with other chapters in this book, especially those that relate to attachment and to the influence of families for young children’s development. Consider what the charts indicate and how they might be interpreted in the light of your own experience and knowledge of family structures, support networks and practices.

EXTRACT 1

The Marmot Review (2010) Fair Society, Healthy Lives. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities Section 2.6.1 Early Years and Health Status, pp60–2

2.6.1 Early years and health status

What a child experiences during the early years lays down a foundation for the whole of their life. A child’s physical, social, and cognitive development during the early years strongly influences their school-readiness and educational attainment, economic participation and health. Development begins before birth when the health of a baby is crucially affected by the health and well-being of their mother. Low birth weight in particular is associated with poorer long-term health and educational outcomes. Lower birth weight, earlier gestation and being small for gestational age are associated with infant mortality. In a study of all infant deaths in England and Wales (excluding multiple births), deprivation, births outside marriage, non-white ethnicity of the infant, maternal age under the age of 20 and male gender of the infant were all independently associated with an increased risk of infant mortality. A trend of increasing risk of death with increasing deprivation persisted after adjustment for these other factors.

Based on this analysis, one quarter of all deaths under the age of one would potentially be avoided if all births had the same level of risk as those to women with the lowest level of deprivation – fig. 2.19.

Figure 2.19 Estimated number of infant deaths that would be avoided if all quintiles had the same level of mortality as the least deprived, 2005–6

Source: Office for National Statistics Health Statistics Quarterly

The first year of life is crucial for neuro-development to provide the foundations for children’s cognitive capacities. There is good evidence to show that if children fall behind in early cognitive development, they are more likely to fall further behind at subsequent educational stages. The evidence also shows that the development of early cognitive ability is strongly associated with later educational success, income and better health. The early years are also important for the development of non-cognitive skills such as application, self-regulation and empathy. These are the emotional and social capabilities that enable children to make and sustain positive relationships and succeed both at school and in later life.

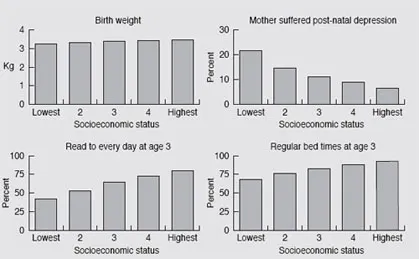

There is an unequal distribution of resources across families in terms of wealth, living conditions, levels of education, supportive family and community networks, social capital and parenting skills. Abundant evidence suggests that socioeconomic status is associated with a multitude of developmental outcomes for children – see fig. 2.20. Furthermore, the literature suggests strongly that socioeconomic gradients in early childhood replicate themselves throughout the life course.

Figure 2.20 Links between socioeconomic status and factors affecting child development, 2003–4

Source: Department for Children, Schools and Families

Pre-school influences remain evident even after five years spent full time in primary school[…] A child’s physical, social, emotional and cognitive development during the early years strongly influences her or his school-readiness and educational attainment, economic participation and health. Children with a high cognitive score at 22 months but with parents of low socioeconomic status do less well (in terms of subsequent cognitive development) than children with low initial scores but with parents of high socioeconomic status. Children of educated or wealthy parents can score poorly in early tests but still catch up, whereas children of worse-off parents are extremely unlikely to do so. There is no evidence that entry into schooling reverses this pattern.

In view of the differences described above, it is unsurprising that educational outcomes at school are strongly related to relative deprivation.

The acquisition of cognitive skills is strongly associated with better outcomes across the life course over a range of domains including employment, income and health. A range of empirical studies provide evidence that cognitive ability is a powerful determinant of earnings, propensity to get involved in crime and success in many aspects of social and economic life as well as health across the social gradient.

POINTS TO CONSIDER

- What do you consider to be foundational elements in the first year of life for healthy cognitive development?

- With reference to the charts in fig. 2.19 of the extract, how do early childhood education and care settings address a range of women’s social and economic conditions relating to pregnancy and birth?

- Consider the evidence from the graphs in fig. 2.20. Discuss how birth weight, maternal postnatal depression, reading and bedtime routines relate to young children’s development.

- What are the implications for practice of the evidence from the graphs in fig. 2.20?

The extract above related particularly to Early Years and health status. It is important to be considered within the perspective of the whole document to gain a fuller view of the ‘social determinants’ of health inequalities as well as the lessons learnt from existing policy, delivery systems and appropriateness of targets. The main policy recom...