![]()

| 1 | Therapy, Ethics and the Law |

Therapy and the law enjoy, at best, an uneasy relationship. They inhabit different spheres of emotion and logic. They employ contrasting languages of feeling and evidence. Each operates in a space that is either essentially personal and private, or is, by definition, highly formalised and public. The points of intersection between therapeutic practice and the law are often obscure, highly specialised and subject to nervous speculation by therapists. The areas of overlap tend to be seen as uncharted territory, full of hazards and pitfalls for unwary therapists, unschooled in the harsh world of litigation. All too often in this area, discussion by therapists is premised on an underlying, and frequently unrealistic, fear of being sued, as a result of imperfect knowledge of the law or of inadvertent negligence.

The starting point for an exploration of therapy and the law is to look at the basic building blocks of any discussion of the topic – law, ethics and therapy. The growing interest in the role of ethics within therapeutic work is linked to ways in which different models of ethics permeate the law. The law may be strongly influenced by a utilitarian, or outcomes-based, approach to ethics, but there are also other, divergent, strands within the law, which emphasise other approaches, such as the concept of individual rights to privacy and confidentiality.

Law

The term ‘law’, as used here, includes all systems of civil and criminal law, including statute, common and case law. As the legal systems of Scotland and Northern Ireland have their own characteristics, the focus here will mainly be on the law relating to counselling in England and Wales. However, basic legal principles will often be fundamentally similar within each of these jurisdictions. The legal system is based on a mixture of statute, or laws passed by Parliament, such as the Data Protection Act 1998 or the Children Act 2004, and common law. The latter embodies long-established principles, regarding confidentiality or contract, which are not necessarily expressed in one single piece of law. Case law is the interpretation of the law made by judges on individual cases, often with far-reaching implications. The Gillick case in 1986, for example, gave legal backing to the provision of confidential contraceptive advice by doctors to young persons under the age of 16. The hierarchy of the courts system, described in Chapter 3, means that decisions taken at one level of the legal system can be overturned by a decision in a higher court, such as the Court of Appeal or the House of Lords. This decision then becomes a point of reference and sets a legal precedent for deciding similar cases appearing before the lower courts.

Ethics

‘Ethics’ is ‘a generic term for various ways of understanding and examining the moral life’ (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001: 1). The study of ethics provides ‘normative standards of conduct or actions’, by exploring what is ‘right’ or ‘correct’ as a moral course of action (Austin et al., 1990: 242). Ethical principles and frameworks can therefore provide assistance in framing decisions about what is morally right or wrong. The main ethical framework relating to therapy is based on the concepts of autonomy, fidelity, justice, beneficence, non-maleficence and self-interest (Daniluk and Haverkamp, 1993; Bond, 2000: 58). These ethical values seek to promote the well-being and self-determination of the client, to avoid harming the client or others, and to maintain the competence of the therapist. They underpin the published codes of ethics and practice, such as those of the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), the British Psychological Society (BPS), and the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP). At certain points, key ethical principles, perhaps those regarding client autonomy and avoiding harm, may be in conflict. This may happen with regard to the issue of preventing suicide, or avoiding harm intended by a client towards third parties. In addition, a therapist may be bound by legal duties which conflict with deeply held ethical principles. As Bond has suggested, ‘What is ethical may not be legal. What is legal may not be ethical’ (2002: 124).

Therapy

The terms ‘counsellor’, ‘therapist’ and ‘psychotherapist’ are self-defined occupational terms, with, as yet, no legal restrictions on their current use. Only the titles of ‘registered medical practitioner’, ‘chartered psychologist’, and ‘registered nurse’ are protected. Anyone can call themselves a doctor, psychologist, nurse, counsellor, social worker, psychotherapist, sexual or marital therapist, or any other therapeutic title, providing they do not mislead patients by falsely claiming to have certain qualifications (Jehu et al., 1994: 191). Statutory regulation of counsellors and psychotherapists has been actively pursued since the 1970s, via the Foster Report (1971), Sieghart Report (1978) and the unsuccessful Psychotherapy Bill (2001). Statutory regulation would introduce restrictions, enforceable by law, on either the use of occupational terms such as ‘counsellor’ or ‘psychotherapist’, or the formal practice of counselling and psychotherapy. The generic terms ‘counselling’ and ‘therapy’ are used here to include a wide variety of forms of therapeutic exploration and resolution, of emotional distress and behavioural problems, using psychological methods, within a dyad, triad or group. The terms ‘counsellor’, ‘psychotherapist’ and ‘therapist’ are used interchangeably here to denote persons carrying out these activities. The distinction between counselling and psychotherapy is one which is widely debated in therapeutic circles, but carries no legal weight outside these narrow confines, and the distinction is unlikely to interest or impress a court of law.

Therapy and the law

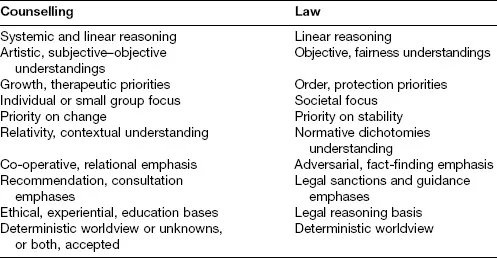

Therapy and the law operate within distinctly different discourses. Whereas therapeutic practice prizes the raw, subjective nature of individual experience, and works with ambiguity and metaphor rather than literal truth, the law is concerned with establishing objective, verifiable facts. Therapists, for the most part, take a cooperative, if challenging, approach to work with clients, in trying to co-construct felt meanings and experiences. Much of the law is based on adversarial proceedings, where one side wins and the other loses, through a robust process of proving, or disproving, contested statements by parties and witnesses. While therapists are at pains to present themselves as being accepting and non-judgmental of client behaviour, however much the latter may be at odds with their own moral standards, the law works towards a final judgment of proven or not proven, guilty or not guilty. Some of the main differences between the respective cultures of therapy and law, perceived from a US perspective, are set out by Rowley and MacDonald, in Box 1.1.

Box 1.1 Relative differences in culture between counselling and the law

Source: Rowley and MacDonald, 2001: 424

The authors highlight a key difference between lawyers and therapists. ‘Attorneys conceptualize, strategize and represent a case for their clients. They generally speak for their clients. Counselors, on the other hand, typically encourage clients to speak for themselves’ (2001: 426). Of course, the differences between these two professional groups may be overstated. The law has increasingly accommodated itself to the value of therapeutic activity, such as pre-trial counselling for victims of abuse, and counselling as a pre-condition for some sensitive processes, such as seeking adoption records or undergoing fertility treatment (see Chapter 8). Many therapists choose to work closely with the law, by writing court reports or by acting as an expert witness. Bruner’s work suggests that narrative theory is the closest area of parallel and overlap between therapy and the law, in that both activities are based on a form of purposeful story-telling. Given the premise that stories provide ‘models of the world’ (Bruner, 2002: 31), it follows that ‘a legal story is a story told before a court of law’ (2002: 37). While both client and plaintiff may tell a story in their own terms, the latter does so in a public, highly formalised arena, with serious personal and social consequences.

To sum up, law stories are narrative in structure, adversarial in spirit, inherently rhetorical in aim, and justifiably open to suspicion. They are modelled on past cases whose verdicts were favorable to them. And, finally, they are really consequential, since the parties involved must have standing and must be directly affected by their outcome. (Bruner, 2002: 41)

Therapists may need to recognise more fully the value to some clients of ‘having their day in court’, and of having their story vindicated in front of a judge and jury. For their part, lawyers might also need to accept that ‘in pleading cases, they create drama, indeed, are sometimes carried away by it’ (Bruner, 2002: 48). This aspect of a narrative approach to the workings of the law is emphasised by Burnett, when reflecting on his fictional account of jury service in the US.

a ‘story’ hangs together, is treated whole. But once you tell your story into the law, it becomes the object of a precise, semantic dissection. The whole of the story is of no interest; instead, patient surgeons of language wait and watch, snip and assay, looking for certain phrases, certain words. Particular locutions trip particular legal switches and set a heavy machine in motion. (2002: 50)

Therapists, highly skilled in detecting affect and meaning in their clients’ words, in the privacy of the counselling setting, thus enter into a very different paradigm in the courtroom. This kind of close, adversarial attention to language in a public setting can be unsettling and de-skilling for many therapists, who may be keen to preserve the integrity of the client’s original story from this kind of scrutiny. There are, however, limits to a narrative approach as a means to understanding legal processes. Some critics would point to the role of enduring structures of authority, deeply inscribed by factors such as gender, class and power, which a narrative approach is in danger of understating (Foucault, 1991; Lees, 1997).

Therapists and the law

Whatever their misgivings and uncertainties, therapists are ultimately bound by the law. However, the BACP Ethical Framework for Good Practice in Counselling and Psychotherapy does not require practitioners to obey the law as such. Instead, there is a broader and looser requirement that ‘Practitioners should be aware of and understand any legal requirements concerning their work, consider these conscientiously and be legally accountable for their practice’ (2002: 6). This represents a significant change from the earlier BAC Code of Ethics and Practice for Counsellors, which clearly stated that ‘Counsellors should work within the law’ (BAC, 1992: para. B.2.6.1).

This shift appears to recognise that therapists may well have difficult choices to make, for example concerning the disclosure of sensitive client information about past criminal offences, or of current suspected child abuse. It is not necessarily helpful to perceive the law as a monolithic structure which will always dictate a clear and obvious course of action. Quite often, legal principles will be in direct conflict, so that a therapist may decide to maintain client confidentiality, which would be a position strongly supported by common law and statute. Alternatively, the therapist may decide to break confidentiality in the public interest, a completely contrary position, but one that is also strongly supported by common law and statute. The key point is that therapists remain accountable for their decisions, both in an ethical sense and in terms of the law.

Therapists need to develop a basic, working knowledge of the law in order to work safely and competently within their ethical code or framework. The relationship of the law to therapy is, however, fairly complex. It is mediated by three main factors:

- by the context or setting in which the practitioner practises, e.g. whether working in a statutory agency, voluntary organisation, or in private practice;

- by the nature of the specific client group the practitioner is working with, e.g. children, or clients with significant and enduring mental health problems;

- by the practitioner’s employment status, i.e. whether the therapist is employed or self-employed.

Thus a therapist working with young people in a secondary school would need to have a good grasp of child protection requirements, whereas another, working as a private practitioner, would benefit from having a working knowledge of the basic principles of contract law. A therapist in primary care, working with clients recovering from severe mental health problems, will need a basic understanding of the Mental Health Act 1983. A self-employed supervisor might want to be clear about the differences between personal and vicarious liability, both for herself and for her supervisees.

Ethical principles and the law

None of the previous statements should be taken as suggesting that the law should be a primary focus for therapists, or, indeed, that the law should drive the priorities of therapeutic work with clients. If anything, it needs to be ethical principles that inform and energise therapeutic practice, but in the context of an awareness of what the law may require of both client and therapist. Changes in the professional regulation of therapists have shifted away from prescriptive and ever-lengthening codes of ethics, towards more demanding, but flexible, sets of ethical principles, which make allowances for therapists’ differing work settings and client groups. The BACP Ethical Framework, for example, adopts many aspects of the broader, relativistic framework of biomedical ethics (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001). In addition to principles, it includes values, such as increasing personal effectiveness, and virtues, such as integrity and wisdom, to produce a complex and multi-faceted system for ethical decision-making. In doing so, it has decisively moved away from the position adopted by the earlier BAC Code of Ethics, where one key principle, that of respect for client autonomy, was clearly ‘the ethical priority’ (Bond, 2000: 58).

Ethical principles

Therapists will be familiar with the key principles set out in the BACP E...