Introduction

In health services research, asking the right question is important because everything else hinges upon it, such as your choice of study design, the interpretation of your results and their impact on clinical practice. Often when a researcher is having difficulty with designing the research, it is either because the methodology is inappropriate for answering the question, or the question itself is inappropriate. The focus and nature of these questions vary according to the perspective of the individual asking them. Patients and carers focus on issues often of immediate personal relevance such as the relief of symptoms or where to get treatment; clinicians bear in mind the broader issues, taking into account, for instance, the range of interventions available and the wider implications of choosing different treatments; whilst funders and researchers seek justification for an intervention and whether clinical care can be improved and/or money saved with it. For example, if a child had a sore throat, their question may be: ‘When will I feel better so that I can play out?’ The parent may ask: ‘Should I take him to the doctor?’ The doctor may ask: ‘Is it a bacterial or viral infection? Are antibiotics needed?’ The funder of the health care may ask: ‘Can we afford to routinely analyse throat swabs?’ The researcher may then ask: ‘Can we formulate an algorithm from signs and symptoms of illness to predict hospitalisation from bacterial infection?’ Given the different perspectives, all of these questions are equally valid.

Questions do not just vary depending on the perspective from which they are being asked; they can often be multi-layered and interdependent. Breaking the overarching question down into what is known and unknown will help, but this is partly reliant on one's own current knowledge and the lengths one is prepared to go to read and critically appraise the peer-reviewed published literature on that topic (please see Chapter 3: ‘Critical Appraisal’). With the exponential growth in the number of medical journals in recent years (Smith, 2006), online literature searching is now an important element of the clinician's and researcher's armoury and it has become relatively easy to find out if a particular question has already been asked in full, or in part, and whether the methodology was robust enough to inform clinical practice (please see Chapter 2: ‘Finding the Evidence to Support your Research Question’). Although this step seems initially a lot of effort, several purposes are served by it; it increases your knowledge of the field in general, starts to delineate the frontiers of what is known and not known at the present time and thus helps develop or refine your research question. Your literature search will also provide references for when you start to write up your protocol, grant or ethics applications, or findings, and can provide you with templates of good-quality research design. It is important to distinguish between when there is no evidence because a study has posed the question and come up with a negative result and no evidence because no study has actually asked the question yet. However not every question requires evidence. There has never been a single randomised controlled trial proving that parachutes are a safe intervention when you jump out of a plane at a great height (Smith and Pell, 2003) for example, but that does not mean we should not use them!

The culture of enquiry and collecting evidence in clinical practice has moved through a series of stages from early descriptive pioneering work on individual patients, such as the work of Edward Jenner who tested the smallpox vaccine initially on one person in 1796, through to more population-based evaluative studies in recent times (please see Chapter 10: ‘Epidemiology’). The importance of evidence-based medicine has slowly gained momentum, challenging the idea that health care professionals, by the simple virtue of reading medical texts and their own anecdotal experience, have some sort of unique insight or unquestionable ‘clinical judgement’ into the social causes of disease (The Lancet, 1995). In 1747, the Scottish physician James Lind conducted the first clinical experiment, in which he researched treatments for scurvy. The results clearly showed that including citrus fruits in the diet produced the best recovery, but the medical establishment and Lind himself was wedded to the idea that scurvy was a disease of putrefaction, curable by the administration of elixir of vitriol (sulphuric acid) and other remedies designed to ‘ginger up’ the system such as mustard, or horseradish. It was another 50 years before the British Admiralty accepted the evidence of the first trial and recommended that lemon juice should be issued routinely to the whole fleet (Vale, 2008).

With the emerging disciplines of statistical techniques in the early part of the 20th century and computing technology in the latter, evidence-based medicine has thrived and become more sophisticated in terms of research designs and methodologies, together with an increased understanding of the complexity of the different issues involved in the research process, for example, sources of potential bias, missing values, etc. However in essence, evidence-based medicine is founded on a simple bottom–up approach that integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patient choice (Sackett et al., 1996), and which begins with a clinical question. It might be a new treatment that needs testing, a particular problem that needs solving or a more general desire to improve the patient's well-being.

What is a Good Question?

A good question in health services research is one that is important and which will give a meaningful answer. For example, there would be no importance in researching a superseded medication or technique, or researching something when the definitive answer for it already exists from previous research. For people new to research, many of their initial questions are aimed at solving the problems of the world, which by their very nature are largely unanswerable. Although this enthusiasm is commendable, there needs to be a degree of ‘funnelling’ whereby a large topic is broken down into smaller more manageable ones, to generate an answerable clinical research question. By breaking the topic down to answer individual key questions elegantly and robustly, your results will remove the uncertainty about those parts, and so the knowledge about the larger topic slowly moves forward. An answerable question in research terms is one which seeks specific knowledge, is framed to facilitate literature searching and therefore follows a semi-standard structure (Bragge, 2010). This process is critical because if a methodological approach is used to address a question that is too broad, lacks rigour, would be difficult to rerun or refine, and would create inefficiencies once the research process is under way, it would fail to answer the research question. Conversely a question that is too narrow may generate more questions than answers, findings would be less generalisable and therefore not worth the time of the researchers or the money of the funders.

It seldom happens that a researcher gets the question right first time. Indeed, most research questions undergo a series of iterations before the team are certain that the question they have framed is appropriate and timely. After reviewing the literature or discussions with colleagues and patients, aspects of your research question may change, such as the population, intervention or comparison. This sort of refinement and transformation of the question is common but does not happen quickly. Discussions are often frequent and lengthy before the whole team is agreed that they have an important and answerable question. Do not underestimate the importance of involvement of patients and public in this step, as your research needs to be meaningful and acceptable to those whom it will affect (please see the case study and Chapter 16: ‘Patient and Public Involvement in your Research’).

Case Study

A study is being conducted regarding the effectiveness of steroids in children with asthma. The research team identified ‘coughing at night’ and ‘days lost at school’ as important outcomes to be measured. However, after discussing the study with parents of these children at the planning stage, it was revealed the most serious concern of the parents was the effects of long-term steroid use. Thus, research about the effectiveness of steroids would be redundant as, regardless of their efficacy, the intervention would not be acceptable to the parents of the children. The research team therefore refocused their question, to ascertain the minimum dose regimen of steroids and its relationship to efficacy. Due to their involvement strategy, they know that this information would be welcomed by the patients and their parents, and therefore more likely to influence clinical practice.

Research Question Criteria

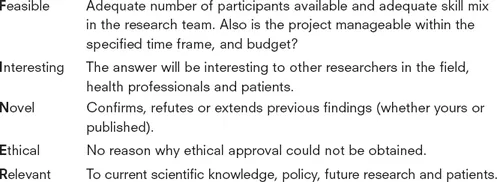

There have been several criteria formulated to ease the process of drafting a good research question, such as the FINER criteria (Hulley et al., 2007):

Whereas the FINER criteria outlines the important aspects to consider in general, the PICO criteria; Population, Intervention or Indicator, Comparison (if relevant) and Outcome (Richardson et al., 1995) is useful for the development of a specific research question. A clear, answerable research question has three or four...