![]()

1

Personality Measurement and Testing: An Overview

Gregory J. Boyle, Gerald Matthews and Donald H. Saklofske

A colleague recently remarked:

Psychologists who specialize in the study of personality and individual differences spend a lot of time coming up with various descriptions of people, like Machiavellianism, external locus of control, openness to experience, and neuroticism. Even more effort is spent trying to measure these ideas with tests like the MMPI-2, brief anxiety scales, and Rorschach Inkblots. But do they really tell us anything about human behaviour in general or about the individual? Does it make a difference in how we view people, select them for jobs, or guide therapy choices and assist in evaluating outcomes?

This is a very loaded question, and the one that appears to challenge both the technical adequacy of our personality measures, but especially the construct and criterion validity or effectiveness of personality instruments in describing individual differences, clinical diagnosis and guiding and evaluating interventions. Technically, there are very few actual ‘tests’ of personality – the Objective-Analytic Battery being an exception. Most so-called ‘tests’ of personality are in fact, self-report scales or rating scales based on reports of others. Such scales quantify subjective introspections, or subjective impressions of others’ personality make-up. At the same time, it is a relevant question and one that we will continue to face in the study of personality and the application of the findings, including assessment of personality, within psychological practice areas such as clinical and school psychology, and within settings such as the military, business and sports psychology, among others. Volume 1 in this two-volume series is devoted to a critical analysis of the theories, models and resulting research that drive the personality descriptions and assessment discussed in Volume 2. Demonstrating both the construct and practical validity of personality descriptions is essential to psychology as a scientific discipline and empirically grounded practice/profession.

THE STATUS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

In a recently published paper focusing on psychological assessment, the following claim was made:

Data from more than 125 meta-analyses on test validity and 800 samples examining multimethod assessment suggest four general conclusions: (a) Psychological test validity is strong and compelling, (b) psychological test validity is comparable to medical test validity, (c) distinct assessment methods provide unique sources of information, and (d) clinicians who rely exclusively on interviews are prone to incomplete understandings. (Meyer et al., 2001: 128)

The authors also stated that multiple methods of assessment in the hands of ‘skilled clinicians’ further enhanced the validity of the assessments so that the focus should now move on to how we use these scales in clinical practice to inform diagnosis and prescription. This is a remarkable accomplishment, if accurate, and even a bold claim that has not gone unchallenged. Claims (a) and (b) have been attacked on various grounds (e.g. see critiques by Fernández-Ballesteros, 2002; Garb et al., 2002; Hunsley, 2002; Smith, 2002). Furthermore, the debate about the clinical or treatment validity of psychological assessment and the added or incremental value of multimethod assessment is argued by some not to rest on solid empirical ground (e.g. Hunsley, 2002; Hunsley and Meyer, 2003), in spite of such carefully argued presentations on the utility of integrative assessment of personality with both adults (e.g. Beutler and Groth-Marnat, 2003) and children (e.g. Riccio and Rodriguez, 2007; Flanagan, 2007). In fact, this is very much the argument put forward by supporters of RTI (response to intervention) in challenge to the view that diagnostic assessment, using multiple assessment methods, should point the way to both diagnosis and intervention planning (see special issue of Psychology in the Schools, 43(7), 2006).

While the Meyer et al. review focused on all areas of psychological assessment, it does suggest that the theories and models, as well as research findings describing various latent traits underlying individual differences have produced sufficient information to allow for reliable and valid measurement and in turn, application of these assessment findings to understanding, predicting and even changing human behaviour associated with intelligence, personality and conation (see Boyle and Saklofske, 2004). While there has been considerable progress, but certainly not a consensus in the models and measures used to describe intelligence and cognitive abilities, the other main individual differences’ areas of personality and conation have travelled a somewhat different path to their current position in psychological assessment.

Calling this a remarkable accomplishment also has to be put in the context of time. Psychological science is only slightly more than 125 years old. As a profession that applies the research findings from both experimental and correlational studies in diagnosis, intervention and prevention in healthcare settings, schools, business and so on, psychology is even younger. Specializations that are heavily grounded in psychological assessment such as clinical, school, counselling and industrial-organizational psychology only began to appear more or less in their present form in the mid-twentieth century. While it can be debated, the success of the Binet intelligence scales in both Europe and North America in the early 1900s, followed by the widespread use of ability and personality instruments for military selection during World War I in the US, and the growing interest in psychoanalysis complimented by development and use of projective measures to tap ‘hidden’ personality structures, provided the strong foundation for the contemporary measurement and assessment of personality.

A BRIEF HISTORICAL NOTE ON PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

However, history shows that the description and assessment of individual differences is not new to psychology. Sattler (2001) and Aiken (2000) have provided brief outlines of key events in cognitive and educational assessment during the several hundred years prior to the founding of psychology, and one can clearly sense that the ‘tasks’ of psychological measurement were being determined during this time. Prior to the creative scientific studies by Galton in the nineteenth century, the first psychological laboratory established in 1879 by Wundt, and psychology’s earliest efforts at measuring the ‘faculties of the mind’ during the Brass Instruments era (e.g. James McKeen Cattell), there is a long history documenting efforts to describe the basis for human behaviour and what makes us alike all others and yet unique in other ways. As early as 4,000 years ago in China, there is evidence of very basic testing programs for determining the ‘fit’ for various civil servants followed by the use of written exams some 2,000 years ago that continued in various forms through to the start of the twentieth century. Efforts to understand and assess human personality also have a long history that predates the study of psychology. Centuries before the psychoanalytic descriptions of Freud, who argued for the importance of the unconscious and suggested that the putative tripartite personality structure of the id, ego and superego were shaped by a developmental process reflected in psychosexual stages, the Roman physician Galen contended that human personality was a function of the body secretions (humors). Galen subsequently outlined the first personality typology characterized by the choleric, melancholic, sanguine and phlegmatic types.

Interest in such processes as memory and reaction time, and efforts to assess and distinguish between mental retardation and mental illness were already underway before the establishment of Galton’s psychometric laboratory in London and Wundt’s and Cattell’s psychophysical laboratories in Germany and the US respectively. While much of this work was focused on the study of intelligence and cognitive abilities, it laid the foundation for psychological testing and assessment that has shaped the face of psychology today. Probably the greatest impetus for test development came as a result of the success of the Binet intelligence tests, first in France and then in the US. The use of tests to classify school children according to ability was followed by the development and use of the Army Alpha and Beta tests to aid in the selection of recruits (in terms of their cognitive abilities) for military service in the US Army. However at that same time, it was also recognised that there was a need to identify military recruits who might be prone to, or manifest the symptoms of, psychological disorders. Woodworth (1919) created the Personal Data Sheet that presented examinees with a questionnaire not unlike those found on scales tapping psychiatric disorders to which a ‘yes–no’ response could be made. While there was not a control or check for ‘faking good–faking bad’ protocols, the measure was deemed to be a success. Thus, well before the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), constructed by Hathaway and McKinley (1940, 1943) and its revised version (MMPI-2, 1989), as well as the California Psychological Inventory (CPI; see Gough, 1987), and other more recent personality measures, Woodworth’s (1919) Personal Data Sheet, was followed shortly after by other personality scales such as the Thurstone Personality Schedule (Thurstone and Thurstone, 1930) and the Bernreuter Personality Inventory (Bernreuter, 1931), which may be considered the earliest personality measures, atleast employing a contemporary questionnaire format. Of interest is that other measures being constructed around the same time highlighted the divergent views on personality assessment methods at the time including the Rorschach Inkblot Test (Rorschach, 1921) and the Human Figure Drawings (Goodenough, 1926) and the Sentence Completion Tests (Payne, 1928).

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE VERSUS PSEUDOSCIENCE

The basis by which current psychological assessment methods and practices can be separated from other attempts to describe the latent traits and processes underlying differences in human behaviour is the very fact that they are grounded in scientific research, as outlined in the editors’ introduction to Vol. 1. It is science that forces a method of study, including objectivity, experimentation and empirical support of hypotheses, and requires the creation and testing of theories. Psychology requires the operationalizing of variables and factors to be used in a description of human behaviour. In contrast to pseudosciences that operate outside of this framework and rest their case in beliefs, personal viewpoints, and idiosyncratic opinions, psychology also demands replication and, where possible, quantification of measures.

Measurement is the cornerstone of psychology and has spawned a number of methods for gathering the very data that may demonstrate the usefulness or lack of usefulness of a theory or provide the information needed to describe a particular human personality characteristic or even diagnose a personality disorder or clinical condition. Pseudosciences such as astrology, palmistry and phrenology, which compete with psychological views of personality, do not require such objective evidence to support their claims; rather, vague ‘theories’ are treated as fact and so-called evidence is often tautological. Thus a strength of psychology is that it has as its basis measurement that includes varying methods of gathering data to test theoretical ideas and hypotheses, as well as strict adherence to psychometric measurement principles such as reliability, validity and standardization (cf. Boyle, 1985).

FOUNDATIONS OF PERSONALITY MEASUREMENT AND ASSESSMENT

As mentioned above, it was concurrent with the advent of World War I that a major effort to assess personality characteristics was first witnessed. Prior to that time, the closest measure of personality would likely be considered as the word association techniques used by Jung. Today almost everyone is familiar with personality measures, self-report questionnaires and rating scales that most often appear in the form of a statement or question (e.g. ‘I am a very nervous person’; ‘I enjoy activities where there are a lot of people and excitement’) that the client answers with a ‘yes–no,’ ‘true–false’ or an extended scale such as a 5 or 7 point or greater Likert-type scale with anchors such as ‘always true of me–never true of me’ or ‘definitely like me–not at all like me.’ These highly structured measures contrast with the more ambiguous, subjective and open-ended techniques most often found in projective instruments such as the Rorschach Inkblot or Thematic Apperception tests.

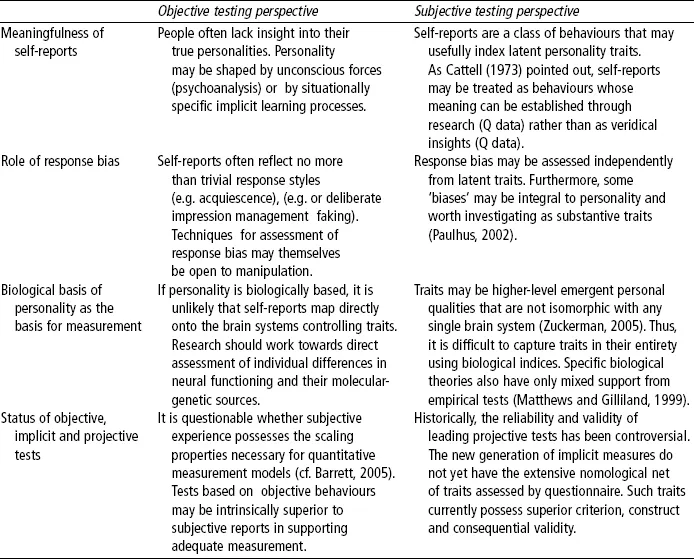

Indeed, there is a longstanding tension between objective and subjective strategies for personality assessment (see Cattell and Johnson, 1986; Schuerger, 1986, Vol. 2). Use of questionnaires based on subjective insights and self-reports has dominated the field, but one may wonder how much this dominance reflects the convenience and low cost of questionnaire assessment. Advocates of objective testing may legitimately question the validity of subjective experience and the apparent ease with which desirable responses may be faked. Table 1.1 sets out the key issues dividing the two camps; both have strengths and weaknesses. We do not take a position on which approach is ultimately to be preferred; the chapters in Vol. 2 illustrate the vitality of both subjective and objective measurement approaches. Ideally, multimethod measurement models in which subjective and objective indices converge on common latent traits are to be desired, but current measurement technology remains some way from achieving this goal.

Given the more common use of standardized personality measures such as, for example, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2), the California Psychological Inventory (CPI), the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF), the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire - Revised (EPQ-R), and the NEO Personality Inventory – Revised (NEO-PI-R), a brief description of the strategies underlying their construction will be presented here. Kaplan and Saccuzzo (2005) provide a useful description of the various strategies employed in constructing personality measures. Deductive strategies employ both face validity (logical–content strategy) and theory-driven views of personality. However, the assumption that an item followed by a ‘yes’ response, on the basis of content alone (‘I am frequently on edge’) taps anxiety or the broader neuroticism dimension found on scales assessing the Big Five (NEO-PI-R) or the three Eysenckian dimensions (EPQ-R) may or may not be accurate. And for instruments that employ a face-validity perspective, the rational approach to constructing items to measure particular characteristics may provide the client motivated by other alternative needs with the opportunity to provide inaccurate and biased responses (e.g. see Boyle et al., 1995; Boyle and Saklofske, 2004). For example, a scale purportedly tapping aggression with items such as ‘I often start fights’ or ‘I have never backed down from a chance to fight’ may be so transparent as to increase the likelihood that examinees will also be more able to create a ‘false’ impression, depending on their motivation (e.g. early parole or lighter court sentence, malingering).

Table 1.1 Objective vs. subjective assessments of personality – some key issues

The foundational basis for many contemporary personality scales includes empirical strategies that employ the responses of various criterion groups (e.g. anxious vs. non-anxious adolescents) to determine how they differ on particular items and scales. For example, the very successful psychopathology scales, namely the MMPI (Hathaway and McKinley, 1940, 1943) and the revised MMPI-2 published in 1989, and the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventories I, II and III (Millon, 1977, 1987, 2006) as well as the ‘normal’ personality trait scale, the California Personality Inventory or CPI (Gough, 1987), are examples of instruments grounded in this approach to test construction and clinical use. Criterion-keyed inventories employ the approach that is less tied to what an item ‘says’ or any a priori views of what it might be assessing, but rather whether the item discriminates or differentiates a known extreme group (e.g. clinical groups such as depressed, schizophrenic, etc.) from other clinical and normal respondents.

In other instances, statistical techniques, particularly factor analysis, are also used to infer or guide psychologists in determining the meaning of items and, thus, to define the major personality trait dimensions. Cattell’s Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire or 16PF began as a large set of items based on a lengthy trait list that were then reduced to 36 ‘surface traits’ and then further to 16 source traits, said to describe the basic dimensions of personality structure (see Boyle, 2006). In turn, structural equation modelling (see Cuttance and Ecob, 1987) allows personality structure to be examined in the larger context of other psychological variables to portray a more comprehensive and integrated description of human behaviour.

Finally, theory-driven measures draw from descriptions of ‘what should be’ or ‘folk concepts’ (e.g. CPI) and use this as the basis for constructing personality instruments, an example being the Edwards Personal Preference Schedule based on Murray’s description of human needs. The major personality theories that have influenced the measurement of personality include psychoanalysis (e.g. Rorschach Inkblot Test; Vaillant’s (1977) Interview Schedule for assessing defence mechanisms), phenomenology (Rogers and Dymond’s Q-sort), behavioural and social learning (Rotter’s I-E Scale) and trait conceptions (Cattell’s 16 PF; Eysenck’s EPQ-R; and Costa and McCrae’s NEO-PI-R).

Certainly, the personality scales and assessment techniques most often employed today, in both research and clinical practice, include a combination of all the above approaches. The Eysenckian measures (e.g. MPI, EPI, EPQ/EPQ-R), the Cattellian measures (e.g. 16PF, HSPQ, CPQ; CAQ), as well as Big Five measures such as the NEO-PI-R have relied on empirical and factor analytic input into scale construction. Thus, the argument may be made that the NEO-PI-R, in spite of varying criticisms (see Boyle, Vol. 1), is a popular instrument for assessing putative trait dimensions labelled extraversion, neuroticism, conscientious...