![]()

1

PARTY SYSTEMS IN THE UK: AN OVERVIEW

CONTENTS

The Westminster party system

1945-70: the era of classic two-party majoritarianism

Post-1974: the emergence of latent moderate pluralism

Regional party systems

Scotland

Northern Ireland

Wales

Party systems in local government

Conclusion

Notes

The aim of this chapter is to provide an overview of contemporary party systems in the UK. This serves as an important contextual preface to the detailed account of party politics which follows in subsequent chapters. But what is a party system? In general, a ‘system’ consists of a recurring pattern of interaction between a set of component elements; thus, the term ‘party system’ refers to a recurrent pattern of interaction between a set of political parties. Furthermore, it is useful to think of parties as competing and/or cooperating with one another. From this, we may infer that a party system is a particular pattern of competitive and cooperative interactions displayed by a given set of political parties. This definition is particularly significant since the central argument of this chapter will be that, since 1970, the UK has moved some way from its traditional status as a classic exemplar of majoritarian democracy towards its polar antithesis as a model, that of consensus democracy. Fundamental to these alternative models of democracy are the twin phenomena of competition and cooperation between party elites; although it would be quite wrong to suggest that cooperation between parties never occurs in majoritarian systems, there can be no doubt that it is far more prevalent in consensus democracies. Accordingly, this chapter can be understood as arguing, inter alia, that inter-party cooperation has become somewhat more typical than hitherto in the UK.

The majoritarian and consensus models of democracy were developed as ideal-types by Arend Lijphart in order to illuminate a basic dichotomy which characterizes the world’s democracies. As he says, these models provide fundamentally different solutions to the problem of how to ensure democratic rule:

Who will do the governing and to whose interests should the government be responsive when the people are in disagreement and have divergent interests? One answer is: the majority of the people… The alternative answer to the dilemma is: as many people as possible. (Lijphart 1984: 4)

The essence of the former approach lies in the idea that the majority (which may in fact be a simple plurality rather than an absolute majority) takes full and undiluted control of the reins of power. This ‘winner-takes-all’ principle generates a set of features which Lijphart identifies as innate to a majoritarian democracy. These include: the concentration of executive power in the hands of one-party governments; the ‘fusion’ of executive and legislative power so that the cabinet (sustained by the disciplined support of a cohesive majority in parliament) dominates the legislature; a two-party system based on a single dimension of competition and a first-past-the-post electoral system; pluralist competition between interest groups; a centralized system of unitary government; the sovereignty of parliament; ‘asymmetric bicameralism’ in which the lower house of parliament (wherein resides the government’s majority) takes clear precedence over the upper house; a flexible, uncodified constitution which cannot restrict the sovereignty of the parliamentary majority; the absence of mechanisms of direct democracy (such as referenda) which might interfere with the sovereignty of parliament; and a central bank which is subject to control by the political executive.

By contrast, the consensus model of democracy entails all that is contrary to majoritarianism, including: the sharing of power in coalition governments; a clear separation of legislative and executive power so that it is impossible for the latter to dominate the former; a multi-party system based on multiple dimensions of political conflict and a proportional electoral system; a coordinated or corporatist system of interest group behaviour in which compromise is the aim; decentralized or federal government; a system of judicial review under which the constitutionality of parliamentary law can be determined by courts; ‘balanced bicameralism’ in which minority representation is the special preserve of an upper house with powers that are genuinely countervailing to those of the lower house; a codified constitution which guarantees minority rights; recourse to direct democracy; and an independent central bank which cannot be controlled by the political executive (Lijphart 1984: chs 1, 2; Lijphart 1999: 3–4).1 Although neither of these models has existed anywhere in its pure form, there are cases which have come close to exemplifying them. Thus, while Switzerland and Belgium are cited by Lijphart as the nearest empirical referents of the consensus model, the UK and New Zealand (until 1996) can be regarded as their majoritarian equivalents. Consensus systems are best suited to the needs of ‘plural’ (which is to say divided) societies in which rival linguistic, ethnic or religious groups can all share power, whereas the majoritarian principle is most functional in relatively homogeneous countries like Britain, in which there are held to be no great cultural divisions.

Even from this very brief account, it is apparent that the party system can best be understood as part of a wider political and institutional settlement. Two points about the place of the party system in this settlement require particular emphasis. First, the classification of the party system according to the numerical criterion (two-party or multi-party?) is important. Second, as we have already seen, the extent of inter-party cooperation varies between these different types of system: for instance, in a two-party majoritarian system parties do not expect to share office, whereas they do in multi-party consensus democracies. Therefore, the analysis of party system development which follows focuses particularly on the number of parties in the system (or to put it differently, on the extent to which the system is fractionalized), and on changing patterns of inter-party competition and cooperation.

In addition, it should be noted that parties interact in more than one political arena and at more than one level of political jurisdiction. Specifically, party systems operate in electoral, legislative and executive arenas, and at local, regional, national and European levels of jurisdiction. Within England, elective regional political authorities do not currently exist, but within the UK as a whole a broader conception of ‘regional’ jurisdiction is emerging. As a result of referenda held in 1997 and 1998, a separate Scottish parliament, and assemblies for Northern Ireland and Wales have been established.2 Moreover, these directly elected representative bodies are accompanied by political executives,3 which means that it is appropriate to conceive of party systems operating within the electoral, legislative and executive arenas of each region.4 The European level is somewhat different, however, for thus far British parties’ interaction in the European Union is restricted mainly to the electoral arena (that is, through contesting European parliamentary elections). In the legislative arena (the European Parliament), they generally operate as members of transnational party groups (such as the Party of European Socialists to which the Labour Party federates itself), rather than as discrete national entities (Hix and Lord 1997). Moreover, there is no ‘European government’ based on political parties, which means that national parties do not really interact in the EU’s executive arena at all. Thus, the one EU arena in which UK parties clearly operate as distinct entities is the electoral one – and in fact it is even questionable just how far there really is an authentically ‘European’ electoral arena in a British context given the ‘second-order’ nature of elections to the EP (Reif and Schmitt 1980). That is, the major British parties and most voters appear to regard EP elections largely as mid-term referenda on the national government’s record in office, which seriously undermines these contests’ status as ‘European’ elections (Heath et al. 1999). For these reasons, the analysis which follows excludes any attempt to account for the manner in which UK parties interact at the level of the EU.

In view of the foregoing discussion, it is apparent that statements to the effect that ‘Britain has a two-party system’ are in reality gross simplifications which beg questions about which level of political jurisdiction and which arena of party interaction one is talking about. To put it another way, it implies that the country actually has more than one party system, and that quite different patterns of party interaction may be found within these different systems; thus, we would doubtless discover, should we care to look, a variety of systems across the 440 principal local authorities which currently exist in Britain, many of which contrast quite starkly with that which we associate with Westminster. It is equally plain that the Scottish party system is significantly different to the Westminster party system, whichever political arena one refers to.

That said, it remains common practice to speak of ‘the party system’ and to mean by this the pattern of party interaction we find in the various national level political arenas. This has not been entirely unreasonable in view of the fact that since 1945 the UK has broadly been a majoritarian democracy with a centralized and unitary state, subject to the formal sovereignty of the parliamentary majority in Westminster. However, given that (a) this tradition of majoritarianism has generally come under some pressure since 1970, and (b) the specific advent of devolution has formalized the political significance of (some) regional jurisdictions in the UK, it has become more appropriate to take account of party system change at central, regional and local levels. We shall start, therefore, by considering the national party system, before evaluating regional and local systems.

The Westminster party system

1945-70: the era of classic two-party majoritarianism

Explicit in much of the literature on electoral behaviour and party competition in the UK is the notion that something started to change after the general election of June 1970. From 1945 to 1970 it is perfectly appropriate to speak of party interactions in Britain in terms of the classic two-party system which is inherent to majoritarian democracy; thereafter, matters are not so clear-cut. Of course, it has never been literally true that only the two major parties have contested or won voter support in Westminster elections, nor even that only they have won representation in the House of Commons. So why should we insist on speaking of ‘two-partism’? Because, of course, in some sense it seems to us that only the two major parties are really important to an understanding of the essential dynamics of the system. This, in turn, reflects the fact that the major parties in ‘two-party’ systems (a) absorb most of the votes cast in elections and (b) are consequently able to dominate the business of government. Thus, only two parties in the system really ‘count’. While Giovanni Sartori has suggested widely acknowledged ‘rules for counting’ parties (based on what he calls their ‘coalition’ and ‘blackmail’ potential [1976: 122–3]), Lijphart has pointed to anomalies generated by these rules (1984: 117–18) and directs us instead towards a well-known measure developed by Markku Laakso and Rein Taagepera (1979). Their formula for counting the ‘effective number of parties’ takes account of both the number of parties in the system and their relative strength. This is a very intuitive and useful technique of measurement since it tells us, for instance, that in any system comprised of just two equally strong parties, the effective number will indeed be 2.0, while a system consisting of three equally strong parties will generate an effective number of 3.0, and so on. This measure can be calculated either on the basis of party shares of the popular vote (the effective number of electoral parties [ENEP]), or on the basis of shares of seats won in parliament (the effective number of parliamentary parties [ENPP]).5

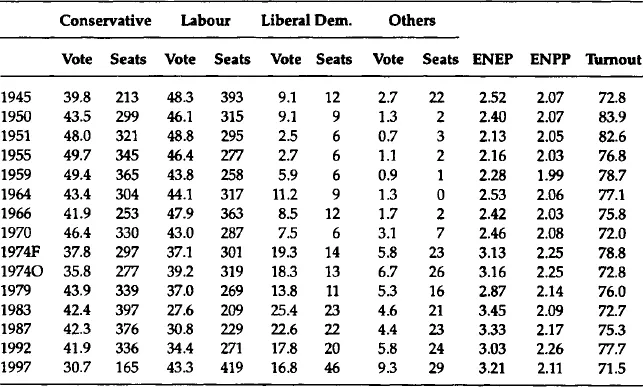

Table 1.1 reports general election results since 1945 and clearly shows a growth in the effective number of parties after 1970. Given the distorting effect of the ‘first-past-the-post’ single-member plurality (SMP) electoral system (see Chapter 9), this is less pronounced in respect of parliamentary parties than electoral parties, though it is still apparent. Thus, while the average ENPP for 1945–70 was 2.05, it increased to 2.18 for the period from 1974 to 1997; the ENEP average shows a more marked increase, from 2.36 (up to 1970) to 3.17 (post-1970). In effect, there is now a two-party system in the national legislative arena, but a multi-party system in the national electoral arena.

It is possible to elaborate considerably on the essential nature of the classic two-party system in the period up to the mid-1970s. In doing so, it is especially helpful to utilize criteria devised by Jean Blondel (1968) and Giovanni Sartori (1976). These suggest that two-partism consists of a number of key features. From Blondel, we understand it to be defined by (a) the high proportion of votes absorbed by Labour and the Conservatives up to and including the election of June 1970 (90.3% on average after 1945) and (b) the high degree of electoral balance between these parties (the mean difference between them in terms of the percentage of the national vote won being 3.9%). Together, these two conditions ensure that competition in the electoral arena was almost entirely about direct confrontation between the two major parties – third parties rarely intruded. In 1964, for instance, the major parties finished in the first two places in some 93% of constituency contests in mainland Britain (574 out of 617).

From Sartori, we see that two-partism consists of three further conditions which particularly relate to the legislative and executive arenas. First, there should be a predominantly ‘centripetal’ pattern of competition between the major parties as they seek the support of the median voter; that is, major parties on both the left and the right can be expected to adopt ideologically moderate programmes in an attempt to maximize their electoral support. (Implicit in this, you will note, is Lijphart’s view that majoritarian two-party systems are characterized by competition along a single predominant ideological dimension.) As we see in Chapter 4, the logic of centripetal competition has been broadly appropriate to Britain in the post-war era. This is not to suggest that the major parties lack distinctive ideological identities, and neither is it to deny that there have been periods of ideological polarization when one or other (or even both) of the major parties have moved away from the ideological centre-ground; this happened, for instance, during the mid-1980s. However, those parties departing from the logic of centripetal competition have generally met with electoral disappointment and have eventually sought a return to the centre (New Labour being a notable example). Thus, centripetal competition may reasonably be regarded as a model of long-run equilibrium in the post-war British context.

| TABLE 1.1 | UK general election results since 1945 |

Notes:

‘Liberal Dem.’ refers to the Liberal Party for the period 1974—79, and the SDP-Liberal alliance in 1983 and 1987. ‘ENEP’ refers to Laakso and Taagepera’s index of the effective number of electoral parties in a system; ‘ENPP’ refers to the effective number of parliamentary parties (Laakso and Taagepera 1979). See also note 1.5.

Sources:

Nuffield election studies; British Governments and elections website

(http://www.psr.keele.ac.uk/area/uk/uktable.htm).

This in itself is interesting since it implies a surprisingly high degree of shared ground between the parties. Indeed, it may well be that without this, majoritarian democracy could not be as stable as has generally proven the case in the UK; were governmental programmes to oscillate wildly from one extreme to another, the essential homogeneity of interest which underpins majoritarianism would be undermined, as would system performance and legitimacy. Perhaps it is not surprising, therefore, to discover that research conducted by Hans-Dieter Klingemann and his colleagues reveals that, in much of the period between 1945 and 1985, British governments were prone to taking over ‘obviously popular ideas’ from opposition party agendas (1994: 262). This suggests that at least some of the apparent adversarialism of British party politics is surface rhetoric; indeed, during periods of relatively close proximity to each other, confrontational language is a virtual necessity in order for the major parties to distinguish themselves in the eyes of ordinary voters. (By contrast, consensus democracies require parties to tone down their very real differences of identity and interest in order that divided societies do not disintegrate politically.) The danger, however, comes if one party wins power so emphatically or consistently that it feels tempted to ignore completely the agendas of other parties or social minorities; in such circumstances, it might be suggested that two-partism gives way to dominance by a particular party, someth...