![]()

SECTION C

Collecting and Analyzing Data

![]()

15

Qualitative Research Review and Synthesis

Jennie Popay and Sara Mallinson

INTRODUCTION

Policy makers, service providers and laypeople often seek information from research (what academics call evidence) to help them make decisions about health care. The type of research evidence they are looking for will vary depending on the issues at stake and the questions asked. For example, questions about the effectiveness of interventions in health, social care and education are best answered by findings from high-quality experimental studies, particularly randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In contrast, for questions about the experience of services, findings from qualitative studies will be the best source of information/evidence. Importantly, however, combining the results of multiple studies using systematic review methodologies will produce more reliable evidence than findings from a single study.

The development of robust systematic methods for the review and synthesis of findings from multiple research studies with the aim of informing policy and professional practice has a long history (Oakley, 2000). Over the past few decades, and particularly in health research, systematic reviews increasingly have replaced the traditional literature reviews used in many disciplines to produce overviews of current knowledge in a particular field, to inform the development of new research and on occasion to inform policy and practice (See for example, Petticrew and Roberts, 2006; Pope et al., 2006). Most of this methodological work has focused on the systematic review and synthesis of numerical evidence on the outcomes of interventions/services, although one formal approach to the synthesis of findings from multiple qualitative studies – meta-ethnography – was first published more than two decades ago by the American social scientists Noblit and Hare (1988). However, until recently, the idea of synthesizing findings from multiple qualitative studies was not taken seriously.

Resistance to systematic review of qualitative studies can be linked to two factors. Historically, the possibility that findings from qualitative research could have policy and practice relevance was not widely accepted and as a result, few literature reviews of qualitative research were supported by funding bodies. Additionally, the idea that systematic syntheses (as opposed to descriptive summaries) of findings from multiple qualitative studies was both methodologically possible and scientifically justifiable was hotly contested. However, in the past decade things have changed dramatically. The number of published papers reporting methodological research and substantive systematic reviews of qualitative research has increased rapidly (see for example, Estabrooks et al., 1994; Jensen and Allen, 1996; Britten et al., 2002; Arai et al., 2005; Dixon-Woods et al., 2006a, 2006b; Popay, 2006; Roen et al., 2006; Noyes and Popay, 2007). The Cochrane Collaboration now has a Qualitative Research Methods Group and the Collaboration’s 2008 Handbook has a section on the review and synthesis of qualitative research (Noyes et al., 2008). It is now widely accepted that qualitative research has an important contribution to make to the evidence base for all areas of policy and practice and for laypeople (Murphy et al., 1998; Dixon-Woods and Fitzpatrick, 2001; Mays et al., 2005). Researchers now agree that reviews of qualitative research can and should be more systematic than they have been in the past.

It is important to acknowledge that debates about the legitimacy of synthesizing findings from multiple qualitative studies continue and that many methodological challenges remain. In the context of these debates an increasing number of qualitative researchers are adopting a pragmatic position noting for instance that while ‘concerns about theory, method and in particular, the issue of context are important they should not prevent us attempting to build a cumulative knowledge base’ (Pope et al., 2007:873). In this spirit of pragmatism, systematic, rigorous and transparent methods for the review and synthesis of findings from multiple qualitative studies have been developing apace. Several detailed overviews of these approaches have been published including practical examples of their use and discussions of associated methodological challenges (e.g., Patterson et al., 2001; Dixon-Woods et al, 2004; Pope et al., 2007). Importantly, these writers highlight the dearth of evaluative data on the relative merits and limitations of different approaches.

In this chapter, we: (1) identify the potential contribution systematic reviews of qualitative research findings can make to the evidence base for decisionmaking by policy makers, professionals and laypeople; (2) describe the general characteristics of the process of systematic review and synthesis as applied to qualitative research and how it differs from systematic reviews of effectiveness evidence; and (3) discuss four examples of approaches to systematic review appropriate for use with qualitative evidence offering guidance on how potential reviewers might best decide which approach to use.

THE CONTRIBUTION OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH SYNTHESIS

The value of qualitative research to policy and practice is frequently presented in one of two general ways. The first emphasizes the enhancement role of qualitative research as adding value to the findings of quantitative research. The second emphasizes the different and unique contribution qualitative research makes to knowledge about the social world: why people behave the way they do, the relationship between social structure and individual/collective agency, between policies and practices, understanding and action, experiences and values.

Qualitative research reviews can help extend quantitative reviews of effectiveness by helping to formulate appropriate questions to be asked and identifying relevant outcome measures. They can also help in the interpretation of the results of quantitative reviews by offering insight into why actions/interventions are or are not effective in certain situations and/or with particular groups. Alternatively, systematic reviews of qualitative research can answer questions that are different from questions of effectiveness. By illuminating the needs of particular population groups, systematic reviews of qualitative research can point to new types of actions/interventions to meet these needs and highlight barriers and/or enablers to the implementation of interventions that have been shown to be effective in ‘real life’. As examples discussed later illustrate, a single systematic review of qualitative research findings may both enhance the relevance of effectiveness of reviews and answer unanticipated, but critical questions.

THE PROCESS OF QUALITATIVE EVIDENCE REVIEW AND SYNTHESIS

At its simplest – and regardless of the question being addressed or the type of evidence included – the process of systematic review involves the juxtaposition of findings from multiple studies with some analysis of similarities and/or differences of findings across studies. More sophisticated approaches, such as statistical meta-analysis and meta-ethnography for example, involve attempts to ‘combine’ findings from multiple studies (through processes of integration or interpretation) with the aim of producing new knowledge.

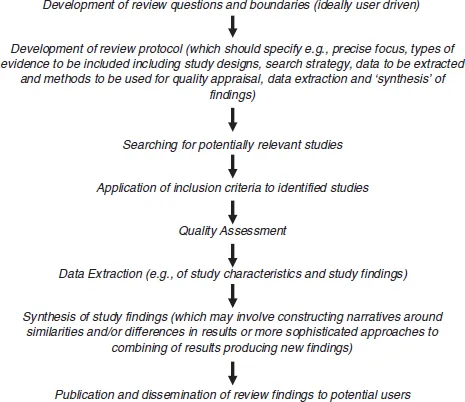

At one level, all systematic reviews include the same basic elements shown in Figure 15.1. Within an effectiveness review, these elements form a linear staged process regulated by strict rules to ensure that potential for bias is, as far as possible, removed. For example, in an effectiveness review, the protocol acts as a ‘rule–book’ for the conduct of the review with reviewers. For the review to be registered with an organization such as the Cochrane or Campbell Collaboration, reviewers are required to submit the protocol to peer review and, once finalized, to adhere to the processes and methods it describes. The published protocol is also a way of ensuring that the review process is transparent from the beginning and can act as an audit tool at the end.

Figure 15.1 Generic elements of the systematic review process

Once the parameters of the review are set – for example, agreeing on the precise questions and the population groups and outcomes that are to be the focus – they should not be changed. In order to limit publication bias favouring positive results, searches should be as comprehensive as possible within resource constraints, with reviewers attempting to identify all relevant studies, published and unpublished. The process of excluding certain study designs and studies with methodological flaws also serves to reduce bias.

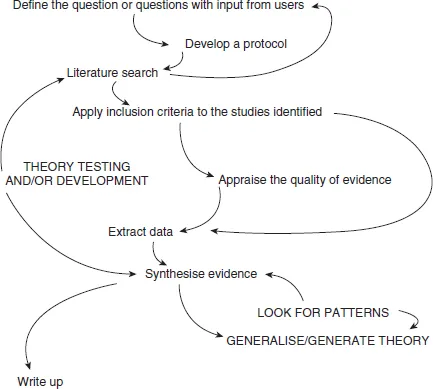

Although these basic elements can be identified in most systematic reviews of qualitative studies, the nature of the processes involved are profoundly different. Perhaps most importantly, regardless of the specific approach adopted, the defining characteristic of systematic reviews of qualitative research is that they involve iterative rather than linear processes. This is powerfully illustrated in Figure 15.2 taken from the book on systematic review of qualitative and quantitative evidence by Pope et al. (2007: 22).

It is good practice to produce a protocol for a qualitative systematic review, keeping in mind that this operates as an enabling framework guiding the review rather than a straitjacket. All reviews should focus on questions that are specified as clearly as possible before the review begins with active input from potential users of the review. However, in systematic reviews of qualitative findings, the question may be revised as the review proceeds. The ‘currency’ of synthesis in qualitative research reviews is the concepts that emerge from the analytical process, not variables chosen prior to data collection and defined in numerical terms. Therefore, whilst it is possible to identify outcomes of interest in the protocol for a quantitative effectiveness review, it is not possible to identify in advance of a systematic review of qualitative research what the concepts of interest will be. These will be identified as the review proceeds through the literature search, data extraction and synthesis. At any point, reviewers may decide to revise the question(s) being addressed or the criteria for including studies in the review.

Figure 15.2 The interactive nature of review and synthesis of qualitative evidence

Identifying potentially relevant studies is also an interactive process. These may be identified through a comprehensive search but they may also be identified through a sampling strategy which could be random and/or purposeful. As data extraction and synthesis proceeds, reviewers may go back to the literature to purposefully identify studies to fill gaps or to search for ‘deviant cases’. Most qualitative research reviews involve an appraisal of study quality but this aspect of the review process is perhaps the most contentious. Important questions are still to be resolved such as: when is study quality appraisal best done; what is the nature of the appraisal process, and how are the product(s) of appraisal most appropriately used? The technical appraisal of quality is not necessarily the same as an appraisal of the relevance and worth of a study to the review (Popay and Williams, 1998). It is also vital to recognize that questions about ‘truth claims’ are very different in the context of qualitative research reviews. The application of appraisal processes and standards of evidence as rigid checklists informing an ‘in/out’ decision has been argued to be inappropriate for qualitative research review (Popay et al., 1998; Dixon-Wood and Fitzpatrick, 2001). Even qualitative studies of generally mediocre or poor methodological quality may generate useful findings for a qualitative evidence review (Pawson, 2006a).

Given these unresolved issues, it is not surprising that there is no consensus over the role of study quality appraisal in systematic reviews of qualitative research. As a result, if methodological quality is assessed, it is typically not a criterion for deciding whether a study is to be included or excluded but rather is taken into account as part of a process of exploration and interpretation in the synthesis process (Spencer et al., 2003). Reviewers may, for example, accord studies different weights in a synthesis depending on the fit between the study design and the review question and/or a study’s methodological quality.

Figure 15.2 also highlights the pivotal role of theory in the systematic review of findings of qualitative research. Petticrew and Egan (2006) have argued that there is a general neglect of the potential for systematic reviews to both test and develop theory. This neglect is particularly significant in qualitative evidence review. In an important sense, the quality of a synthesis of qualitative evidence will be determined by the visibility of the theoretical perspectives informing the review and the extent to which the synthesis process has involved theory testing and generation. At its simplest, the product of a qualitative research synthesis will be the juxtaposition of concepts/themes extracted from included studies. This is typically embedded in a discussion of similarities and differences and the analysis may also include a count of the most and/or least common themes. In the qualitative research community, there is rightly anxiety about such ‘atheoretical’ analyses and the potential for ‘thin’ thematic description to replace ‘thick’, theoretically connected and enriched analysis.

A recent systematic review of qualitative research on parents’ decision-making about childhood vaccination provides an example of the limitations of thematic syntheses that fail to develop the potential of theory (Mills et al., 2005). The product of this review was a simple listing of recurring themes in qualitative research on parents’ perspectives on vaccination. The list highlights how parents feel about vaccination but fails to add to our understanding of ‘why’ they feel and/or behave the way they do. Good quality qualitative research not only describes the meanings that people attach to their experience of the social world, it can also reveal the purpose these meanings serve. For example, primary qualitative research on the experience of chronic illness moves beyond descriptions of people’s accounts of their experience of their illness to argue that through these narratives, people reconstruct a sense of worth in a social context in which illness has moral overtones (Williams, 1984). From this perspective, Mills and his colleagues (2005) have produced an initial descriptive synthesis of qualitative research on parents’ views on vaccination, but the ultimate aim of a synthesis of qualitative research should be to move these useful but limited lists onto a higher conceptual level that has more explanatory purchase (Popay, 2005; Pawson and Bellamy, 2006). It is also throug...