![]()

1

Psychotherapy, Culture and Storytelling: How They Fit Together

Only in the middle of the twentieth century has psychotherapy and its multitude of variants (counselling, counselling psychology, clinical social work, clinical theology, self-help groups, bibliotherapy and so on) developed a solid institutional base in professional associations and universities, become accessible to significant numbers of people, and taken its place at the heart of modern society. Since that time, therapy has on the whole thrived. In most countries some degree of government control has been applied to therapy, with the introduction of regulatory bodies and licensing bestowing ‘official’ legitimacy to this practice. Therapy has also entered the realm of everyday awareness, to the extent that references to therapy in popular culture media such as magazines and TV series are commonplace, and are made with the tacit assumption that everyone in the audience will know what is meant.

Most people involved with therapy, either as practitioners or as clients, seem to take for granted its status as a form of ‘treatment’ or ‘intervention’ appropriate to certain types of emotional, behavioural or relationship problems. Few pause to consider the implications of the relatively recent emergence of psychotherapy, or of its classification as a type of ‘treatment’. Nevertheless, the fact is that while other occupations such as farmer, lawyer or physician have been around for a long time, the occupation of counsellor or psychotherapist did not exist in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. Something happened to make psychotherapy possible. What happened? What were the factors behind psychotherapy arriving on the scene when it did, and in the form that it took?

There are basically two ways of accounting for the emergence of the psychological therapies around the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One explanation points to advances in psychiatric and psychological knowledge that led to the discovery of this new form of treatment. From this perspective, therapy can be seen as part of the ‘technology’ of psychology and psychiatry. Doing therapy involves the application of scientifically validated theories and procedures to problems of emotional life and behaviour. This way of looking at the development of psychological therapies places them firmly within the theme of ‘progress’ and ‘improvement’ that permeates much of modern life.

The other approach to explaining the rise of therapy looks not forward with science and progress but backward toward some very old cultural traditions. From this perspective, all cultures possess ritualised ways of enabling members to deal with group and interpersonal tensions, feelings of anger and loss, questions of purpose and meaning. These rituals evolve and change over generations, and are part of the ‘taken-for-granted’ fabric of everyday life. Looked at in this light, psychotherapy can be viewed as a culturally sanctioned form of healing that reflects the values and needs of the modern industrial world. As such, it has not been ‘invented’ by scientists but has evolved from the healing practices employed in previous historical periods by ordinary people, and necessarily contains within it the residue of these earlier forms.

The vast majority of books and articles on psychotherapy are grounded in a scientific perspective. Therapists trained in any of the mainstream approaches acquire a theory of therapy that is framed in terms of abstract propositions and cause-and-effect relationships. I am assuming the reader’s familiarity with at least the general shape of this literature, so will not be rehearsing in any detail the mainstream science-based account of how discoveries and advances by the like of Freud, Wolpe and Rogers laid the foundations of psychotherapy as an applied science (see Freedheim, 1992). Instead, I intend to approach the question ‘why has therapy arrived now?’ by examining the cultural history of psychotherapy, and by exploring the implications for theory and practice of looking at therapy as a cultural form. This discussion will review the cultural origins of therapy, the transition from religious to scientific modes of intervention, and the construction of psychotherapy as an applied scientific discipline.

My basic thesis is that stories and storytelling represent the primary point of connection between what goes on in ‘therapy’ – whether contemporary psychotherapy or traditional religious healing – and what goes on in the culture as a whole. From a cultural perspective, a therapy session is a site for telling certain stories in a certain way. The telling of personal stories, tales of ‘who I am’, ‘what I want to be’, or ‘what troubles me’, to a listener or audience mandated by the culture to hear such stories, is an essential mechanism through which individual lives become and can remain aligned with collective realities. It seems to me impossible to imagine a human culture that did not contain such a mechanism. In recent times, however, this process of ‘life narration’ has become deeply problematic. It is no longer clear whether existing forms of psychotherapy can provide adequate means for people to tell the stories they need to tell in the ways they need to tell them.

‘People’ have changed: a brief cultural history of the concept of the person

In arguing that it is important to understand psychotherapy and counselling in cultural and historical terms, I am acutely aware of the difficulties involved in any attempt to make sense of human behaviour in earlier times, or in other cultures. There seems no real escape from the dangers of both misinterpreting other ways of life by imposing frameworks of understanding derived from present-day experiences and practices, and of oversimplifying what are enormously complex matters. In acknowledging the sketchiness of the account that follows, I hope I may also stimulate others to fill in some of the detail, or even to attempt to re-draw the whole picture.

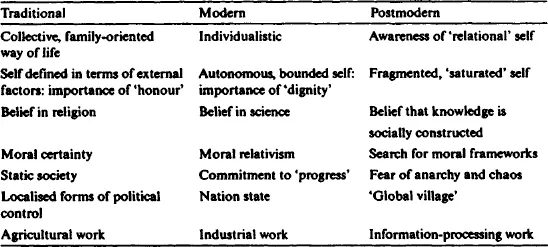

My sense of this area of inquiry is that the advanced industrial societies of Europe and North America can be understood to have undergone three main stages of cultural development. The first, and earliest stage can be characterised as traditional culture, which began to break down around about the eighteenth century. In traditional culture, people live in small, mainly rural communities, have relatively basic technologies to hand, and live according to an explicit set of moral guidelines mediated by religion and myth. In the modern era, the advancement of science and technology was associated with a gradual movement toward urban, industrial ways of life and a replacement of religion by rationality and a belief in progress. In the late, or postmodern era of the present moment, there appears to be a fragmentation of the structures and assumptions of modernity. There is an increasing questioning of the ‘project of modernity’, which is almost folding in on itself, or is even regarded as responsible for the destruction of the human spirit and the planet on which we live. However, it is far from clear where all this is leading. The late twentieth century is regarded by many as a time of transition. We are perhaps moving away from the age of modernity, but no one really knows where we are heading to. It can even be argued that ‘postmodern’ culture represents no more than a capacity to look back on modernity, to reflect on it, rather than a movement in any particular direction. Table 1.1 presents a summary of some of the main themes associated with traditional, modern and late/postmodern cultures.

Table 1.1 The key characteristics of traditional, modern and postmodern cultures

Although therapy is embedded in, and grows out of, the forces of history and culture, its main focus is on the detail of individual lives. The differences between the traditional, modern and postmodern worlds exist not only at the level of social organisations, institutions and forms of communication, but also at the level of the individual person. The sense of what it is to be a person is socially constructed. It depends on the relational web, the belief and kinship systems, the economic order, into which one is born. And the sense of what it means to be a person has changed. Therapy is both affected by this change and has helped to bring it about.

The feel of what it might be like to be a person in traditional times is captured in these passages from Philippe Ariès and Alasdair MacIntyre:

The historians taught us long ago that the King was never left alone. But in fact, until the end of the seventeenth century, nobody was ever left alone. The density of social life made isolation virtually impossible, and people who managed to shut themselves up in a room for some time were regarded as exceptional characters: relations between peers, relations between people of the same class but dependent on one another, relations between masters and servants – these everyday relations never left a man by himself. (Artès, 1962: 398)

One central theme of heroic societies is . . . that death waits for both alike . . . . If someone kills you, my friend or brother, I owe you their death and when I have paid my debt to you their friend or brother owes them my death. The more extended my system of kinsmen and friends, the more liabilities I shall incur of a kind that may end in my death. . . . The man therefore who does what he ought moves steadily toward his fate and his death. It is defeat and not victory that lies at the end. (MacIntyre, 1981:124)

These accounts offer a way of beginning to understand the stories that people in traditional cultures lived (and live) within: stories of ‘never being alone’ and stories of ‘moving steadily toward my fate’. To be a person in a traditional culture is to live in close proximity to others, in spiritual and psychological as well as physical terms. For such a person the notion of an ‘inner self’ that forms the basis for decision-making and action (Landrine, 1992) is difficult to comprehend: ‘who I am’ is defined externally, through history, kinship, duty and fate.

The sense of personhood in modern society is quite different. It is perhaps helpful to differentiate two aspects of the development of a modern concept of person (Gergen, 1994). One aspect is characterised by the construction of person and relationship through the idea of romanticism. The romantic–modern notion of the person retains the traditional sense of the person being constituted through his or her deep ties with others, but replaces the traditonal embeddedness in community and history with relationships with others (for example, sexual or marriage partners). This aspect of modern personness is reflected in much twentieth-century psychology. For example, the focus of psychodynamic theory on inner ‘self-objects’ and the achievement of intimacy in relationships can be understood as examples of this movement away from a sense of person-in-community to a sense of person-in-relationship. And what accompanied this realignment of ‘what it means to be me’ was the discovery or creation of an inner landscape of a ‘Self with a capital ‘S’. The goals of personal happiness, fulfilment, and loving and being loved by a special other, required, in the romanticist narrative, a thorough exploration and mapping of the individual, bounded Self.

The other central aspect of the modern concept of the person is a sense of the person as a mechanism. There is in modern life an overwhelming importance attached to rationality, control and the abolition of risk. Behind all religious stories is an encompassing macronarrative of how the individual is ultimately subject to the will and guidance of a greater power. Behind all scientific theories is a macronarrative of prediction and control: science makes it possible for human beings to be the masters of the universe. While in the nineteenth century the scientific world-view was restricted mainly to people who were actual scientists or were particularly ‘progressive’, during the twentieth century we have all become scientists. Through theories such as psychoanalysis, behaviourism or cognitive psychology, we are able to explain our own being in scientific, cause-and-effect terms. We are all (faulty) mechanisms.

Cushman (1990, 1995) has argued that the modern configuration of ‘person-ness’, the interplay of romanticism and mechanism, was generated through the efforts of mature capitalist economies to create new markets through the creation of a different type of consumer. He suggests that the sense of inner-directedness and repression of sexuality in the service of love and disciplined work noted by Albee (1977) and others was characteristic mainly of early capitalism. In later capitalist economies, the loss of family, tradition and community, particularly in the post-war middle classes, led to the a general sense of alienation: the ‘empty self’. Cushman writes that:

It is a self that seeks the experience of being continually filled up by consuming goods, calories, experiences, politicians, romantic partners and empathic therapists in an attempt to combat the growing alienation and fragmentation of the era. This response has been implicitly prescribed by a post-World War II economy that is dependent on the continual consumption of nonessential and quickly obsolete items and experiences. . . . Psychotherapy is one of the professions responsible for healing the post-World War II self. Unfortunately, many psychotherapy theories attempt to treat the modern self by reinforcing the very qualities of self that have initially caused the problem: its autonomous, bounded, masterful nature. (1990: 600–1)

Cushman’s account of the conditions under which the modern notion of person-ness arose relies heavily on an analysis of the influence of the industrial revolution, the development of advanced capitalist economies and the movement toward a secular, scientifically oriented, mass urban consumer society. Behind these factors can be glimpsed yet earlier social and cultural processes, for example the slow historical emergence of consciousness (Jaynes, 1977) and the development of literacy (Ong, 1982), and the Western sense of an expressive, instrumental self (Taylor, 1989).

The construction of the modern person has brought with it a vast array of new stories-to-live-by. There are huge classes of narrative that hardly existed in traditional cultures, for example such stories as ‘seeking fulfilment’, ‘falling in love’, ‘getting divorced’, ‘being in therapy’, or ‘choosing a new car’.

Yet the wheel of human culture and history turns yet again, and reveals yet another reconstruction of the person in the late/postmodern era in which we currently live. It is always difficult to capture with any confidence the sense of what is happening now, but the social philosopher Kenneth Gergen has perhaps achieved this task better than anyone else. His notion of the saturated self effectively conveys some of the essential features of life in advanced capitalist economies at the turn of this century. Gergen (1994) describes the ways in which people are now globalised, with the potential to have relationships and roles in all parts of the world, thus giving endless opportunity to view one life from a myriad perspectives. The postmodern person is bombarded by information – satellite, cable, faxes, the Internet, mobile phones and so on. The result of all this is fragmentation. The person is not known by any one other or group as a consistent whole, but experiences himself or herself as different selves in different settings. A whole psychology of multiple personality and ‘sub-selves’ has grown up to enable people to describe these experiences.

Perhaps the most significant new dimension of the stories people tell in late/postmodern times lies in the extent to which these stories are permeated by reflexivity (Giddens, 1991). There are so many alternative life-styles on offer, so many channels of satellite/cable TV serving up apparently limitless repertoires of how to be a person. Eventually, these media of communication converge to drive home one simple message: you can choose who you are. It is no coincidence that in recent years social psychologists have begun to describe the phenomenon of possible selves (Wurf and Markus, 1991). People in modern and postmodern times can look at who they are, and imagine being someone else, in a way that would be impossible for someone from traditional culture.

This classification of social and cultural history into three broad stages – traditional, modern and late/postmodern – is an oversimplification. Fragments of traditional ways of life survive in modern times, and have undergone a revival in some postmodern circles. However, my aim in offering a division of cultural history into these three stages is to highlight my argument that psychotherapy and counselling are essentially products of modernity. Therapy constitutes a crucial element of the cultural apparatus of modern society. As we move further in the direction of whatever the post in late/postmodernity will bring, the nature of therapy will necessarily undergo a transformation as fundamental as that which occurred when the religious ‘cure of souls’ was replaced by psychoanalysis.

‘Psychotherapy’ in traditional cultures

The construction of what we now know as psychotherapy took place over a long period of time, and involved the assembly of many different cultural elements. It is difficult for us to know exactly how psychological healing was conducted in Europe in the pre-psychotherapy era. Most of the historical accounts currently available attempt to classify and interpret traditonal healing in terms of contemporary medical and psychiatric categories. Not enough historical research has looked at how people with emotional, relationship and behavioural problems were actually dealt with in the centuries before these types of problems were medicalised (although see Neugebauer, 1978, 1979). There is, however, evidence available from anthropological studies on non-Western, non-industrialised societies. Material from both historical and anthropological sources can be brought together to give a general picture of some of the ways that ‘problems in living’ can be, and have been, addressed in traditional cultures.

One of the main themes that appears in historical studies of the treatment of psychological disturbance is the importance of religion. In pre-industrial Europe and America, the priest or pastor, and the Church, acted as sources of help for those in psychological distress. Holifield (1983) reports that, in the Roman...