![]()

1

Speech, Language and Communication Impairment Explained

Chapter Objectives

- To set out the aims and framework of the book

- To explore different ways of describing language

- To identify the key components of effective communication

- To provide a framework for understanding language development

- To explore the implications of the interaction between language development and language demands in key stage 3 and key stage 4

1.1 Introduction

Difficulties with speech and language are most closely associated with the early years, so it is easy to assume that students at secondary school or college are able to understand and use language in order to learn. However, this assumption cannot be made for students who have a history of speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) or others who may experience more general learning difficulties.

By the time children with a history of SLCN start the secondary phase of their education any persisting difficulties may be quite difficult to identify. The obvious signs, primarily difficulties with speech, have usually been resolved unless there is a physical cause; for example, cerebral palsy. We are able to understand what they are saying and make the assumption that they are able to understand what we are saying. We also assume that they are able to express their needs, wishes and feelings, if they choose to do so.

The optimistic view that language problems are an issue primarily for the early years was challenged by a national longitudinal study of children with SLCN (Conti-Ramsden and Botting, 1999) which reported that in year 2 only 1% of the estimated 5% of children with specific language impairment had been identified on the special needs registers in school. Four percent of children with SLCN did not have their primary need identified in key stage 1. Children who were the most likely to have had their difficulties identified in their early years and may have had speech and language therapy (SLT) were those who had problems with speech production usually associated either with limited control of the articulatory system or problems with their sound system (phonology). Many of these children would have been discharged from SLT before starting school because their speech was intelligible.

Children with SLCN had often been given a range of other labels or had individual education plans that focused on the secondary effects of their core language problem. Common examples included:

- Dyslexia – when they were slow to learn to read and spell because of the effect of residual problems with their sound system (phonological system) on their ability to access the phonic route to reading.

- Social, emotional, behavioural difficulties (SEBD) – because of the impact that a language impairment may have on social, emotional and behavioural development.

- Autistic spectrum condition (ASC, also known as ASD) – because of the impact that a language impairment may have on patterns of social interaction and social communication. Typically, as the language of these children improves, the early ‘autistic-type’ features recede.

Some children with SLCN who were in the ‘missing’ 4% at key stage 1 may be identified during key stage 2. The two most common markers are: when the children find it hard to access the more demanding language of instruction, or when their decoding skills for reading are found to be in advance of their reading comprehension (Snowling and Stackhouse, 1996). However, there are students who have primary language needs who may transfer to secondary school without their core language difficulties having been identified.

Andy and Alice are typical examples of children whose language needs were not addressed before they started at secondary school.

Andy had a history of behavioural difficulties at school and the Behavioural Support Services has worked with him, his family and the school.

He was referred to the Speech and Language Therapy Service while at infant school but he has refused to co-operate with the assessment.

Andy was included in a transition group in year 6 which met at the local secondary school. He was assessed in school by the educational psychologist during the autumn term year 7:

- Non-verbal abilities – average range

- Receptive language – low average, except semantic knowledge first centile (i.e. 99% of students of his age would be expected to obtain a higher score)

- Expressive language – first centile

- A reluctant communicator – speech not fully intelligible

- Low tolerance of failure when tasks become challenging

- Low self-esteem as a learner – ‘I’m think’

Andy’s behaviour in school was challenging:

- Confrontational and abusive to staff

- Volatile and aggressive to other students

- Refusal to attempt classroom tasks

- Refusal to do homework

Alice attended a mainstream school, moved schools at the time of family breakdown and returned to her first school from year 3 onwards.

Staff at the junior school had no significant concerns about her educational progress or social development, so she was not on the SEN register.

Alice transferred to secondary school having attained levels 3/4 for key stage 2 SATs. In year 9 Alice became increasingly reluctant to attend school.

Assessment by an educational psychologist revealed:

- Verbal skills at 0.3 centile; that is, 99% of students her age would be expected to obtain a higher score

- Social communication skills were an area of relative strength so that she was able to:

- take turns in conversation

- initiate and close a conversational exchange skillfully

- adapt what she said to the needs of the listener

- demonstrate appropriate prosody and non-verbal communication skills

Alice’s relatively strong social skills and social communication skills, together with her age-appropriate decoding skills for reading and encoding for spelling appear to have masked her significant, core difficulties with language comprehension until her inability to access the year 9 curriculum led to school refusal.

1.2 Describing language

Children who are unable to communicate effectively through language, or to use language as a basis for further learning, are handicapped socially, educationally and, as a consequence emotionally. Byers-Brown and Edwards (1989)

It is important for teachers who work with students who have SLCN to be familiar with some of the ways that language is described by other professionals. How language is described often depends on the focus of the describer. Thus, speech and language therapists may find that the analysis of a language profile using a psycholinguistic model (Stackhouse and Wells, 1997) helps to guide the planning of a programme of intervention, while a teacher might find a social interactionist model (Barthorpe and Visser, 1991) a more appropriate way of looking at the needs of a student. The form/content/use model (Lahey and Bloom, 1988) is the preferred model for many CPD courses for teachers (described in Ripley et al., 2001). The many ways of describing language reflect the complexity of language as a system in which different aspects and different levels interact. This section introduces some key terminology that is in common use.

1.2.1 Language delay and language disorder

Every child learns language in their own way. In some cases children show an unusual delay in the development of their understanding of language and/or their ability to express themselves. Difficulties in these areas will inevitably have some impact on the way in which that child uses language in order to communicate. Fortunately, most children with a language delay do ‘catch up’, often before they reach school age. For other children, their language develops in an idiosyncratic way. These individuals are described as having a language disorder and their difficulties may persist into key stage 3 or 4. The language problems may affect their access to the curriculum, as well as their social, emotional and behavioural development.

1.2.2 Effective communication

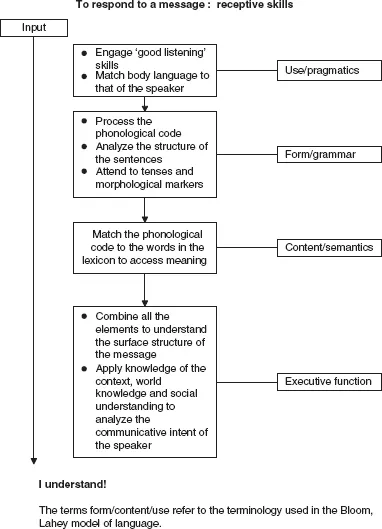

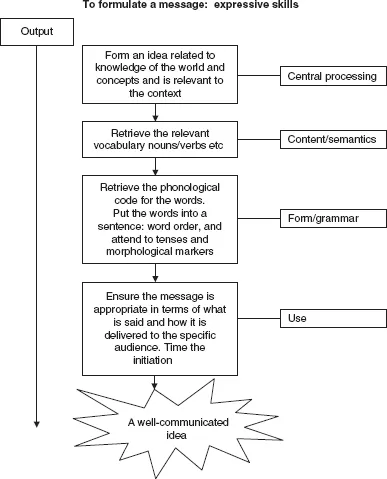

In order to communicate effectively we need to be able to listen and understand what is said to us: receptive language. There are many sub-skills which are needed in order to do this, even if we can hear what is said. These skills are described in detail in Chapter 2. We also need to be able to articulate our thoughts, feelings and needs: expressive language. This is another complex process which is discussed in Chapter 6.

Some students have adequate levels of receptive and expressive language, but experience communication problems associated with how they use their language. This area of difficulty, known as pragmatics, is often the core problem for students on the autistic spectrum. However, students who have difficulties with speech, receptive or expressive language may show secondary problems with the pragmatic aspects of language which recede as their language improves.

The pragmatic aspects of language include the two main components:

- the functions and purposes for which the student uses language

- the way in which the student uses their language (e.g. how they adapt what they say to the ‘audience’).

Pragmatic skills are discussed in Chapter 7. A glossary of terms is presented in Appendix I. It is possible to illustrate the processes involved in effective communication using a basic input/output model (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Figure 1.1 Input/output model.

Figure 1.2 Input/output model.

1.3 Language development

For most children, language acquisition is a robust process but for children with SLCN things do not go according to plan. Normal language development follows a biologically order...