![]()

1 | Early Brain Development, Laterality and Gender Differences |

Brainpower and Boys and Girls

Early brain development – Critical periods and functional changes – Hemispherical characteristics – Laterality – Implications for dyslexia – Gender differences – Gender differences in the educational situation – Some implications for teaching and learning in English – Chapter summary – Teacher activity

□ Early Brain Development

Writing depends upon the use and understanding of speech. The use and understanding of speech depends upon the acquisition of language, and this in turn depends upon early brain development. Motor skills, used in writing, also depend upon brain development, involving the growth of sensori-motor structures and functions leading to hand and eye co-ordination.

Dr Mark Porter, writing in the Radio Times, states ‘The human brain is a complex living computer that weighs just over 2 lbs/1 kg, contains more than 100 billion interconnected cells, and has the consistency of blancmange’ (Porter, 2001). The brain advances more in its development and grows faster in the early years than at any other time in life. At birth it is 25 per cent of its adult weight, but by the age of 5 it is 90 per cent of it, and by 10 years old it is 95 per cent of the final weight (Brierley, 1976). Greenfield refers to this ‘astonishing growth’, and states that by the age of 16 it approximates its adult size (Greenfield, 2000b). All the nerve cells have been present since the middle of foetal life, and none are made beyond that period. Many of the supporting cells, though, grow after birth, and are generally present in large numbers by a year or so. The nerve cells, however, enlarge, develop longer processes and make new connections, which we may visualize through the metaphor of an electric wiring system.

The growth of these is extremely fast, reaching a peak at about eight months old, but still continuing rapidly as general growth takes place. Greenfield (2000a) explains that ‘the advantage of this mind-boggling increase in connections is that it makes the human brain incredibly flexible, able to adapt to the unique life of the individual.’ Furthermore, she adds that the human brain ‘responds to use by making new connections and reforging old ones’, and while depending on the individual persons and their attributes and situations, different parts of the brain may need to adapt more than others. This wiring, then, increases at a phenomenal rate in the early months and years. Regular use stimulates the brain to develop more connections, while neglect has the opposite effect. Experimental evidence shows that areas stimulated more by use show a greater richness of connections (Greenfield, 2000a).

During infancy and childhood, the density reaches even greater levels than in adults. A phase follows when the density begins to reduce, gradually reaching the adult levels. It is thought that perhaps the less useful connections become automatically ‘pruned’; Greenfield refers to this process as one of atrophy (Greenfield, 2000b). Johnson likens this process to that of a newly planted tree, where roots growing into stony ground gradually wither, while those finding fertile soil strengthen and become firmly established (Johnson, 1997).

□ Critical Periods and Functional Changes

While some interactive development is general, other kinds of experience are quite specific in terms of responding to very critical sensitive periods during the growth sequence. If such critical periods are not ‘hit’, or sufficiently stimulated, by environmental experiences, and are missed, deficits can result (Greenfield, 2000a). On the other hand the brain, and particularly the cortex, owns a remarkable plasticity and adaptability, and where critical periods are not involved, development and adaptation can continue to take place.

As well as growth, there are functional changes in children as they develop. For instance, the quality of their movements changes as co-ordination becomes more efficient and refined, and as musculature develops to allow more strength and precision. Compare a 3 year-old kicking a ball with a 7 year-old kicking a ball, or observe a 4 year-old on a tricycle and compare his action with the skill and manoeuvrability shown by a 10 year-old cyclist. Generally, growth tends to proceed outwards towards the extremities, so that an infant reaches out and uses the arm and hand more as a unit rather than being able to adopt a complete range and flexibility of movement in the different parts of the limb. Progression takes place from gross motor skills, i.e. those using limbs and trunk, such as in climbing, kicking, jumping, cycling, to fine motor skills such as drawing, picking up and fitting together small items or using scissors. Movements tend to be overlarge for the fine motor skills to begin with, and lack precise co-ordination, but gradually become fine-tuned. It is also known that some fibre tracts of the brain are not fully functional till around the age of 4, and in particular those involved in the fine control of voluntary movement. This has implications for teachers dealing with young children trying to write, draw, and play with a variety of toys in the nursery and reception classes. Sheridan gives a useful sequence of development in terms of movement and behaviour in the early years (Sheridan et al., 1997).

In order to transmit messages through the nervous system, the nerve fibres need to be covered by an insulating coat or sheath, to preserve the impulse and prevent it leaking away or discharging before it reaches its destination. Our metaphor of electrical wiring gives a ready parallel. First the fibres have to grow. Then the covering, called myelin, develops around them, before they can transmit their messages. The effect of myelinization is sadly demonstrated by its breakdown in the disease known as multiple sclerosis, where patients gradually lose control over many functions. Myelinization is, however, a very prolonged process, and is possibly associated with continually developing sequences of social behaviour, speech, and later with thought processes. Between the ages of 2 and 4 considerable myelinization occurs, allowing the increased development of movement and motor intelligence, and this, in turn, may stimulate more. At puberty, the further surge in myelinization enables far greater control and development in many areas of function and behaviour.

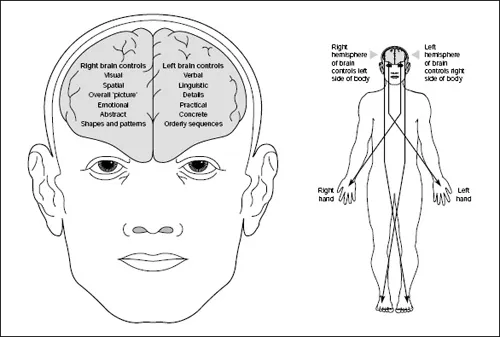

□ Hemispherical Characteristics

Although the brain has the ability to make new connections through external stimulation, despite this plasticity there are certain usual patterns for the various pathways and circuits involved in particular functions within the brain, which are common to most people. Language has a number of related functions, including verbal reasoning, which are normally located in the left hemisphere of the brain, while spatial and non-verbal functions are usually located in the right hemisphere. The brain, with its cerebral cortex over-mantling the rest, somewhat resembles a large grey walnut kernel, with two convoluted hemispheres joined centrally by a harder core, rather like a sunken ridge. The latter is called the corpus callosum, and is an elongated bridge between the two hemispheres where pathways cross from one to the other, enabling intercommunication. This is a crucial crossover effect since the left hemisphere controls the right side of the body and the right hemisphere controls the left side. Most language areas tend to be set up in the left hemisphere, although there are also some specific verbal functions which usually belong on the other side. It is suspected that the right hemisphere may be responsible for prosodic aspects of language, such as intonation and cadence in speech.

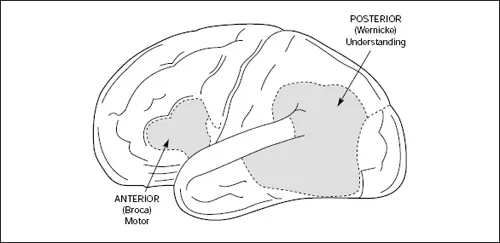

The two hemispheres work together, due to the connections running through the corpus callosum. Paul Broca, a French doctor in the nineteenth century, was the first to realize that there was a specific location for some language functions, through his study of a brain-damaged patient. This area, in the left hemisphere, is now called Broca’s Area (Pinker, 1994; Greenfield, 2000a). There are other areas, too, discovered through studies of brain-damage, such as that first identified and described by Carl Wernicke, a German physician, also of the nineteenth century, dealing with speech impairment. In Wernicke’s aphasia people can articulate satisfactorily, but the content of their speech becomes garbled due to the loss of reasoning elements connected to the speech areas.

Figure 1.1 and 1.2 ■ These figures are reproduced by kind permission of Penguin Books Ltd, from pages 40 and 41 of BRAINSEX: The Real Difference Between Men and Women by Anne Moir and David Jessel, published in London in 1989 by Michael Joseph, copyright © Anne Moir and David Jessel, 1989.

Figure 1.3 ■ The diagram is reproduced by kind permission of John Brierley from Figure 12 in his book

THE GROWING BRAIN, published in Slough in 1976 for the National Foundation for Educational Research.

In a recent study in Japan, participants listened to passages from different literary genres, including a philosophy text, a newspaper report on global warming and some jokes. Brain imaging techniques showed that all genres activated language regions on the left side of the brain, although difficult sequences showed greater activity in the areas known to be involved in processing meaning. The humorous material aroused activation of Broca’s Area augmented by activity in the frontal part of the cortex (Ozawa et al., 2000). Both Broca’s Area and Wernicke’s Area are normally on the side of the left hemisphere, with Broca’s rather further forward than Wernicke’s. Grammatical processing appears to be centred to the front of this, including Broca’s Area, while to the rear of it, including Wernicke’s Area, the sounds of words, especially nouns and some aspects of their meaning are processed (Pinker, 1994). Carter discusses the two important language areas and their roles, suggesting that among the varying causes for dyslexia is a form of dissociation disorder caused by a lack of parallel functioning, i.e. working in concert together, between Broca’s Area and Wernicke’s Area (Carter, 1998). The picture is complex, but the study of braindamaged patients and the modern use of brain scans are rapidly accelerating understanding of such interactive processes today.

□ Laterality

The dominant hand in right-handed persons is controlled by the left hemisphere, which also usually has the speech and language areas laid down within its connections. In left-handed people, the dominant hand is controlled by the right hemisphere, of course, with its greater specialization for spatial and visual aspects of processing, among others. Dominance of one hand or the other is usually well established between the ages of 2 and 3, although some children are much later in arriving at this stage (Sheridan et al., 1997). Carter, in fact, gives evidence that hand preferences can even be discerned prenatally (Carter, 1998). There is, however, some variability in the establishment of handedness. Along with a strong preference for the use of one hand over the other, is the development of dominance of one eye over the other as a kind of ‘lead ‘ eye, and connections formed between hand and eye are important for the efficiency of both fine and gross motor skills through hand-eye co-ordination. One leg or foot is also usually preferred for kicking, stepping off and initiating leg or foot movements. The establishment of the dominant hand, eye and foot are together called the establishment of laterality. In most people the three components of laterality are in line, being all right-sided or all left-sided, and thus controlled by the same hemisphere of the brain. For the majority of people, being right-handed, laterality is right-sided, involving the left hemisphere. The opposite is true for left-handers, despite language centres generally still being located in the left hemisphere for left-handers. However, in some individuals laterality is mixed; this means that either or both the dominant sides for the lead eye and foot are not the same as for the hand.

Pinker thinks that this is determined genetically. He says that ‘90 per cent of people in all societies and periods in history are right-handed, and most are thought to possess two copies of a dominant gene that imposes the right hand (left brain) bias’ (Pinker, 1994). He goes on to add that those with two copies of the recessive version of the gene develop without a strong right-handed bias; in this category are right-handers with some ambivalence, those who are ambidextrous and the left-handers. He also tells us that left-handers are not mirror images of the right-handers. Carter agrees, and tells us that the left hemisphere controls language in virtually all right-handers (95 per cent of these), but the left hemisphere only controls language in about 70 per cent of left-handers, while in the other 30 per cent most have language areas in both hemispheres (Carter, 1998). Pinker suggests that about 19 per cent of lefthanders have most language areas in the right hemisphere (Pinker, 1994). There is some evidence that left-handers, though better at mathematical, spatial and artistic activities, are more susceptible to language impairment, dyslexia and stuttering. Both Carter and Snowling agree with the genetic determination of handedness, but add that it may also be attributable to prenatal influences in some cases (Carter, 1998; Snowling, 2000).

□ Implications for Dyslexia

A wealth of evidence is summed up by Gredler in support of his opinion that an appreciable proportion of dyslexic children show poorly developed laterality or mixed laterality. However, he comments that though this might be interpreted as demonstrating that poorly developed laterality can be linked with incomplete cerebral dominance, it cannot be established as a comprehensive cause, since many children with poor or late establishment of dominance or mixed laterality do not show any difficulties in becoming literate (Gredler, 1977, in Reid and Donaldson; Hulme, 1987, in Beech and Colley). Certainly a sense of directionality is necessary in acquiring reading and writing skills, with a recognition that the letter order in a written word reflects the sound order of the spoken word, and laterality may be linked with this. Some other studies quoted by Gredler have indicated that mixed laterality only becomes a prominent factor below certain levels of general ability, and certainly below average levels of ability. Snowling quotes research showing that although it was expected that left-handers would be at risk of having speech difficulties, including dyslexia, results were not clear, and there was some evidence that children with very strong right-handedness as well as very strong left-handedness were more numerous among poor readers (Snowling, 2000). While the cognitive difficulties of dyslexia are more than likely to stem from inherited differences in the speech processing mechanisms located in the left hemisphere of the brain, further research is needed in this area.

Some children have not developed dominance fully by the time they come to school, or may have uncertain or mixed dominance. Teachers can check for this easily, by giving a kaleidoscope to the child, ensuring that presentation is made centrally towards the chest. The child will then use one or other hand to accept it and will usually place it to the eye on the same side as the chosen hand. If this is repeated on different occasions, and the same hand and eye are used each ti...