The purpose of this book is to provide a short – but interesting and, importantly, critical – account of the rise of knowledge management and its current place in and implications for contemporary management theory and practice. To achieve this purpose it is necessary to explore where knowledge management comes from, what it is, why it is significant and where it is going. This will reveal the value of studying knowledge management in the global business environment. The book is not written solely for prospective or practicing managers – rather it is of relevance to everyone; for knowledge management is not something confined to large private or public sector organizations. Knowledge management of one sort or another is widespread. We are all touched by knowledge management systems of some description. From the Tesco supermarket checkout to hospital appointment systems, from the online booking of flights to the university or college admissions system, organizations collect information about us, analyse it, and use it to create knowledge about our purchasing habits, our travel preferences, our health, our qualifications – and much, much more.

Related to the idea of knowledge management is the popular debate on the knowledge economy, which, replete with associated concepts such as knowledge workers, knowing communities, and knowledge systems, pervades contemporary discussions of the competitiveness of organizations and of national and regional economies. The imperative to manage knowledge derives largely from the desire to improve competitiveness through innovation and through increased productivity, which in turn should arise from the creation and application of knowledge-based assets.

Knowledge: a few initial observations

The challenge of defining knowledge has given rise to a whole branch of philosophy that is concerned with it: epistemology – that is, the theory of knowledge. It would not be possible to explore this immense field in a short book – and the present one has a different purpose.1 Nevertheless, a working definition of knowledge is required. According to the Oxford Dictionary of English (2003: 967), knowledge may be defined as ‘facts, information, and skills acquired through experience or education; the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject … the sum of what is known’. As this formulation indicates, there are several different types of knowledge, for example theoretical and practical. The varied nature of knowledge will be considered in the next chapter. For now, it is useful to begin our exploration of knowledge by drawing a clear distinction between data, information, and knowledge.

First, what is meant by the term ‘data’? Data may be defined as series of observations, measurements, or facts – presented for example in the form of numbers, words, sounds, and/or images. Data have no meaning, but they provide the raw material from which information is produced. Information is defined as data that have been arranged into a meaningful pattern. Data may result from conducting a survey; information results from the analysis of these data in the form of a report, or of charts and graphs that give them meaning. Knowledge may be defined as the application and productive use of information. Knowledge is more than information, because it involves an awareness or an understanding gained through experience, familiarity, or learning. Yet the relationship between knowledge and information is symbiotic. Knowledge creation is dependent upon information, but the development of relevant information requires the application of knowledge. The tools and methods of analysis applied to information also influence knowledge creation. The same information can give rise to a variety of different types of knowledge, depending on the nature and purpose of the analysis.

To illustrate these differences between data, information, and knowledge, let’s take a numerical example:

1 7 5 9 6 4 2 7 0 3 9 8 5 4

Here we have data in the form of a set of numbers. But what does the set mean? It could be a series of recorded observations – say, the number of times 10 individuals are able to catch a ball without dropping it:

17, 5, 9, 6, 4, 27, 0, 39, 8, 54

Combining this information with our existing knowledge, we can perhaps infer that those individuals with a higher number of catches have better hand–eye coordination than those with a lower number. Alternatively, by interpreting the numbers as one whole number, adding a dollar sign, and applying our knowledge of the USA’s economy, we can take this set of numbers to represent the USA’s outstanding public debt in July 2014 (TreasuryDirect, 2014):

$17,596,427,039,854

Imposing some form on the series of numbers transforms the raw data into information. Knowledge takes this process further. To produce knowledge from information, we need to combine this information with our existing understanding of the world, so that we can interpret the former and situate it in a context that gives it meaning.

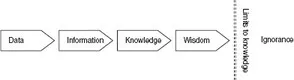

The transformation of data into information and then into knowledge, as described above, illustrates a rationalist perspective on knowledge formation. Such a linear process may go beyond the stage where data constitute the raw material for information production and information provides the input for knowledge, to a stage where knowledge becomes the basis for ‘wisdom’ or ‘meta-knowledge’ – which includes beliefs and judgements (Figure 1.1). Importantly, wisdom recognizes the limits of knowledge and the uncertainties in the world (McKenna, 2005). Hence this is the point where our ignorance must be acknowledged.

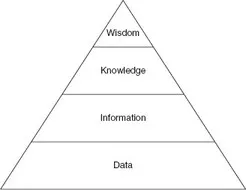

In contrast to this linear representation, the relationship between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom (DIKW) is often represented in a hierarchical form, particularly among those concerned with the management of information. The exact origin of this representation is open to debate, and the DIKW hierarchy has been subject to much consideration and critique (see, for instance, Rowley, 2007, and Frické, 2009). Each tier of the hierarchy is thought to include all the categories below it (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 A linear process of knowledge formation and its limits

Figure 1.2 Data–information–knowledge–wisdom (DIKW) hierarchy

However, as noted above, the relationship between knowledge and information is symbiotic. Indeed the collection of data is also dependent on information and knowledge. Linear or hierarchical interpretations of the interactions between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom fail to employ wisdom in their construction. Acknowledging the full complexities of these interactions and transformations requires recognition that they may be multidirectional, recursive, and/or random. For instance, in the quotation at the beginning of this chapter, which comes from T. S. Eliot’s Choruses in The Rock (Eliot, 1934), the poet and playwright suggests a reversal of the linear process of knowledge transformation outlined above.

In relation to our understanding of the knowledge we acquire from information, we must always be aware that our interpretation is dependent on our past experience and on our worldview. Moreover, in the western philosophical tradition knowledge tends to be defined as ‘justified true belief’. For someone to have knowledge of something, that knowledge (or what is to count as such) must be true, and the person must not only believe it to be true but be justified in holding it – that is, their belief must be subject to empirical validation. But what counts as ‘justified true belief’ is open to question and very much dependent on the perspective from which we interpret empirical evidence. Such perspectives can change over time and in different contexts. Hence knowledge may be viewed as socially constructed.

For instance, before the heliocentric theory of the Renaissance astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus was accepted, it was commonly believed that the earth was the centre of the universe. Copernicus’ theory, published just before his death in 1543, in On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, contradicted accepted understandings of the position of the earth in the universe. Importantly, heliocentrism conflicted with the biblical account, which was of course supported by the powerful Roman Catholic church. Hence the dissemination of this new knowledge was impaired by the social and political structures of the time. Indeed in 1633 Galileo Galilei, the philosopher and astronomer credited with the introduction of significant improvements to the telescope, was tried by the Roman Inquisition for supporting heliocentrism. He was suspected of heresy and placed under house arrest for the remainder of his life.

This example illustrates two important points about knowledge. First, although we may believe that there are certain factual elements of knowledge that are true beyond doubt, we must remember that knowledge is socially constructed and dynamic in nature. Moreover, if we are wise, we will recognize, like the Greek philosopher Socrates, that our own ignorance is always vastly greater than our knowledge. Technological developments like the improved telescope in the early 1600s or the Internet in the twenty-first century can extend the scope of our knowledge; but they do not diminish our ignorance, since with new technologies come new unknowns. In addition, what is recognized as knowledge (or not) is highly contested. And this leads me to the second point: power influences what counts as – or is accepted as – real knowledge. In the seventeenth century the Roman Catholic church had the power to suppress knowledge that conflicted with its own dogma, according to which the earth was stationary and situated at the centre of the universe and the sun and stars rotated around it; and that dogma was accepted as real ‘knowledge’.

The word ‘knowledge’ also possesses positive connotations. For example, who could disagree with the idea that knowledge is good, or that more knowledge is better than less? If knowledge is good, its accumulation and management must also be a good thing. It is this positive view of knowledge that permeates many business texts on knowledge management. Knowledge certainly does have a positive impact, as advances in medical knowledge over the past century demonstrate. Nonetheless, it is essential to recognize that there are negative aspects to it too. For instance, in recent years, major advances in knowledge of the human genome have provided a wide range of medical tests that can inform us about our predispositions to various life-threatening conditions; yet few of us wish to gain such knowledge. Perhaps sometimes ignorance is bliss. We might also question the value of knowledge of how to produce nuclear weapons, or the benefit of an excess of knowledge if it prevents timely decision making.

Hence knowledge is far from neutral; and, as I have already shown, what counts as knowledge is open to debate. The idea that ‘knowledge is power’, first articulated by the sixteenth-century English philosopher Francis Bacon, was later inverted into ‘power is knowledge’ by the twentieth-century French philosopher Michel Foucault (see Foucault, 1979). When considering knowledge, then, it is essential to recognize the power that access to it provides, as well as the way in which power itself can give legitimacy to knowledge claims. Moreover, as the philosopher and historian of science Thomas Kuhn noted, knowledge that reinforces or sits easily with our existing knowledge system is more readily accepted than one that requires a paradigm shift in our worldview (see Kuhn, 1996). Similarly, in societies dominated by rational modes of thinking, knowledge claims based on myth or faith will carry less weight than knowledge claims based on scientific reasoning. Clearly knowledge is complex, and through the pages of this book I will frequently return to the challenges and opportunities that such complexity presents for those who are seeking to manage it.

Knowledge in the economy

In today’s world we are regularly bombarded with media messages telling us how important knowledge is; how we now live in a knowledge economy, where knowledge work is the primary occupation of most of the productive workforce. Nations, organizations, and individuals, we are told, must now live in a globally competitive knowledge environment. National and international organizations – for instance, the Work Foundation, the World Bank, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) – regularly urge policymakers to develop knowledge resources though investments in education and in research and development (R&D). It is against this background of an increasing emphasis on knowledge in the economy that any study of knowledge management must be set.

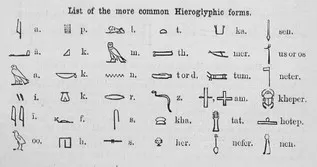

We might ask: ‘Why the sudden focus on knowledge? After all, hasn’t knowledge always been important?’ And, of course, we would be right. Knowledge has always been an important resource. From the earliest human societies until today, knowledge – be it awareness of the habitat and behaviour of prey in hunter-gatherer communities or our ability to contain infectious diseases in the advanced world – has been crucial to survival. As civilizations developed through specialization, trade, and agriculture, the types of knowledge that were available and relevant to the smooth functioning of society expanded and deepened. Methods of recording information in the form of counting devices became necessary. Early systems of writing, such as Egyptian hieroglyphs, emerged around 3000 bc; they were of the pictographic–ideographic variety (Figure 1.3). These forms of writing permitted the recording of a broad range of information, which supported the economic and political structures of the societies in which they developed. The Phoenicians’ introduction, around 2000 bc, of alphabetic writing enabled the expression of any concept that can be formulated in language. The record-keeping requirements associated with the extensive trading activities of the Phoenicians very probably helped to stimulate this innovation: the documentation of knowledge has always been closely aligned to economic activity, whether to count sheep or to control and organize international trade.

Figure 1.3 Common hieroglyphic forms

Source: A Handbook for Travellers in Lower and Upper Egypt. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. Paris: Galignani; Boyveau. Malta: Critien; Watson. Cairo and Alexandria: V. Penasson. 1888. P. 069. Available from Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Available at http://hdl.handle.net/1911/13077 (accessed 31 July 2014). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA.

These early means of recording information and preserving knowledge can be viewed as primitive or incipient knowledge management systems. Prior to their development, information and knowledge would have been passed on through oral traditions and through learning by doing. The central purpose of passing on knowledge – in writing or verbally, through explanation or through demonstration – is to ensure that the recipient does not spend time rediscovering it. And, of course, there is no guarantee that knowledge, once lost, can be easily restored. For instance, after the fall of the western part of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, Western Europe was plunged into a long period (often labelled the ‘Dark Ages’) during which much knowledge was lost – roughly until the Renaissance in the fourteenth century. Transferring knowledge can be more difficult than merely giving a verbal explanation or demonstration. I am sure that, like me, you have occasionally listened attentively to a lecture and yet failed to grasp what the professor seemed to be imparting in an eloquent and seemingly successful manner to other members of the audience. Knowledge transfer, let me repeat, is not a simple process. I will elaborate on this in Chapter 4.

The evolution and persistence of human civiliz...