![]()

Part 1

What are Geographies of Nature?

Figure I.1 A small woodland in Greater Manchester, England

Are spaces for nature self-contained, sealed areas from which all trace of people has been banished? In Manchester, the city in England where I grew up, I remember that most woodlands were strongly fenced off, with warning signs nailed onto the trees saying, ‘No trespassing’, ‘Keep out’, and so on (Figure I.1). I ignored the signs, as did most children. The site in Figure I.1 is fenced off from the public, it’s a local state-owned ‘private’ woodland. The positive side is that it has remained a woodland for as long as I can remember, the negative side is that most people cannot access it. Manchester City Council still has a policy of keeping nature reserves and people apart, fearing that people will interfere with wildlife. Its spaces for nature are, in theory and to some extent in practice, people-less. When applied to bigger areas, like, for example, wildlife reserves in Kenya, the term that is sometimes used for this kind of spatial practice is fortress conservation(Adams and Mulligan, 2003). The fortifications, which include guns, police and permits as well as fences, keep the world of people and the world of nature apart. And yet, when you start to observe these places you quickly note that not only are there numerous surreptitious border crossings (ranging from the rather innocuous fence climbing of my youth to the poaching parties that threaten tiger reserves in India), there are also lots of other crossings. Wildlife officers and volunteers enter the woodlands to clear sycamore saplings, brambles and holly under bush – all in order to maintain the habitat. In the larger projects and parks in India and Keyna, wildlife police, tourists, farmers, children, conservationists, scientists, animals, plants, remote sensing devices and animal medicines all pass through the parks. Meanwhile, fortress nature has long since been a contested practice. There are ongoing arguments over the best way to conserve nature – should people and wildlife be kept apart, or is it better (more realistic, more democratic?) to work towards the in situ co-presence of people and nature?

Both discourses of community participation and sustainable development have been mobilized to undermine what is sometimes regarded as the imperial practice of fortress nature. Whatever the answer, the point is that spatially things are not quite so pure and not so singular. Rather than watertight containers, spaces for nature are more permeable and multiple matters. So how do we think such spaces? This part of the book discusses some possibilities. In Chapter 1, I expand on the (im)possibilities for pure, sealed spaces. The focus is on spatial practices of conservation. The question is raised that, perhaps, given this porosity, is it that there are no spaces for nature, other than in our imperial imaginations? In Chapter 2, I discuss the possibility that nature exists more in human imaginations than on the ground. I look at some of the history of nature, focusing on changing understandings of evolution. In Chapter 3, I introduce a third type of spatial practice, that of enactment. The aim here is to use a number of examples, but mainly ones drawn from understandings of disease transmission, and specifically Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE or mad cow disease), to explore the spatial multiplicity of nature. In Chapters 4 and 5, I build some more specificity into this discussion of enactment. In Chapter 4, I investigate common metaphors used to describe naturecultures, including interaction and hybrids. In Chapter 5, I take this forward to a discussion of nature and difference. By the end of this part of the book the aim will have been to suggest that nature is practised in ways that are spatially multiple. In Part II, the empirical practicalities of geographies of nature, how and why they matter, become the focus.

![]()

Introduction

How do we think about and ‘do’ nature? And what does this mean for the ways in which we spatialize nature? In this chapter I want to explore and make some preliminary judgements upon three possibilities. We can sketch them quickly:

- Nature as an independent state (but threatened by invasion)

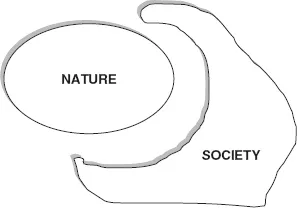

The first possibility is that we understand nature as something that is distinct from, absolutely separate to, the social world (Figure 1.1). Nature is another country, or is a part of ancient history, or buried deep in our make-up. It follows that Nature is real, ‘out there’. ‘Out there’ meaning beyond us, or perhaps outside the ‘in here’ of our minds (so out there can include parts of our human bodies, those parts that are subject to natural urges, rhythms and involuntary movements).

It may also follow that there is little of this nature left – for the social world is spreading, present as much in Antarctica as it is in our hormones. For most of the planet’s inhabitants and history, ‘in here’ has had little or no bearing on the workings of out there. Nature has gone on regardless of human imagination, dreams and schemes. Up until the agricultural, scientific and industrial revolutions of the last millennium, Nature out there was still much the same as it was when humans had barely started to scratch the surface of the planet. More recently this pure unadulterated Nature has become increasingly polluted in some form or other by human processes. The pollution takes at least two forms. First, there is the mixing of forms. Artificial molecules turn up in Antarctica. Second, there is the march of a form of rationality that sees the world as standing reserve, as of value only for human ends. Both mark the death of nature as Carolyn Merchant called it (1990), or the end of nature as McKibben (2003) termed this state of affairs. Not only is nature denuded, humans also suffer through an invasion of their own tissues but also through the repercussions of treating nature as an object to be governed.

In some form or another, this is probably the most common version of nature in Western societies. It informs many types of environmentalism, from the triumphalism of human mastery over nature to Western versions of stewardship and even some deeper green philosophies where nature needs saving from humankind, and humankind from itself. (The literature is vast but two of the best books remain Glacken, 1967 and O’Riordan, 1976).

Figure 1.1 Nature as independent state (threatened by invasion). Nature and Society are separate spaces, but Nature is about to be or has been engulfed by Society.

- Nature as a dependent colony, a holiday home

The second possibility regards nature as mainly, if not wholly, the product of human imagination. It is an idea. What is understood as natural is nothing but a product of the ways in which people order the world. Nature is ideological. It is socially contrived, produced by people and their value systems, political systems, cultural sensibilities. If there is reality, then that reality is social (Figure 1.2). Out there can be explained by in here. Nature, in this version of affairs, is a comforting illusion, or even a trick that people use to convince others of the faultlessness of their arguments (‘it’s natural that we do this, there’s no point trying to change what’s natural’). When we are told that the English Lake District or Niagara Falls are largely artifice, the product of hundreds of years of farming, design, literary and visual work, that they are ways of seeing rather than natural wonders, then we are starting to argue that what is taken to be natural in some quarters is, on the contrary, social all the way down. Likewise, when we contest fixed sexual identities, we’re unsettling the fixity and conservatism of an ideological and already always political nature. Contesting the ideology of nature is often attractive politically, especially for a political project that is interested in gaining freedoms, or opposing those who would constrain liberties.

- Nature is enacted (a co-production)

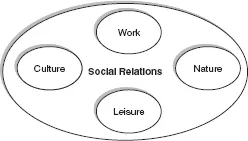

The third possibility I want to consider is perhaps the hardest and we will have to work at the spatial imagery. It suggests that nature and society make one another (so thus are not independent), but aren’t necessarily reducible to one another (so thus are not strictly dependent). This is more difficult, but the basic argument will be that society and nature need not be considered as a zero-sum game. In other words, we do not need to think of a set amount of nature which is progressively eroded as society expands. Rather, the more activity there is in one, the more we might expect from the other.

This might be a more radical and interesting way of understanding nature, and one that this book is in part an attempt to elaborate upon. It’s radical because it might well change the ways in which we attempt to practise nature. So, for example, nature conservation might well be a different practice once we view nature as neither totally independent of, nor totally dependent on, social worlds. It’s also the least intuitive version of nature and requires us to do the most work.

Figure 1.2 Nature as dependent state. Nature is but one of many categories that emerge from and exist within the realm of human actions and orderings. It is therefore dependent on and not prior to social relations.

Three possibilities, each of which has numerous variations and possible trajectories, and which will need a certain amount of teasing apart. You might, as we expand on each of these possibilities, become adept at spotting them in action (indeed, they are at work, practised in all manner of situations). But before we go on, I want to add that they are often mixed together in the same setting, making it more difficult to attach them as labels to organizations, people, or modes of thinking than might be supposed. My hope in raising the third possibility is not necessarily to call for some kind of absolute clarity. Rather, it is to suggest that where nature is concerned, things are often unclear, or not as clear as they seem. Our question then becomes how do we proceed, and proceed well, when clarity is always accompanied by murkiness. But before we get into these debates, it will be useful to use this three-part taxonomy, our three possibilities, to discuss how nature is mobilized in various settings. We will look in more detail at each in turn. In this chapter we will look at the possibility of nature as an independent entity (or, more accurately, its impossibility as I provide a critical review). In Chapter 2, we will explore nature as something dependent on society and culture. Again, the tone is largely critical, and, in being so, both these chapters start to trace the other possibility that I have called co-production. So the remainder of this chapter and the next involve laying groundwork for later chapters.

Nature out there

In our everyday language, we tend to treat nature and society as separate entities. If something is social, then almost by definition it can’t be natural. And if something is described as natural, then it is unlikely to have much to do with society. So, for example, when we describe a landscape as ‘natural’ we often mean to suggest that it is undeveloped, untouched and that the social or human-made world is largely absent. But such a view, attractive and seductive though it can be for some, is often difficult to sustain. William Cronon, in a landmark essay entitled ‘The trouble with wilderness’ (1996a), launches a critique of this independent state version of nature, one that he argues has recently re-emerged in relation to the ways in which biodiversity and its conservation are imagined:

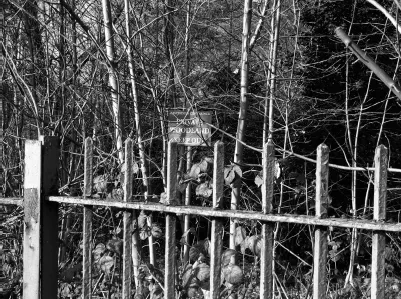

The convergence of wilderness values with concerns about biological diversity and endangered species has helped produce a deep fascination for remote ecosystems, where it is easier to imagine that nature might somehow be ‘left alone’ to flourish by its own pristine devices. The classic example is the tropical rainforest, which since the 1970s has become the most powerful modern icon of unfallen, sacred land – a veritable garden of Eden [Figure 1.3] – for many Americans and Europeans. And yet protecting the rainforest in the eyes of First World environmentalists all too often means protecting it from the people who live there. Those who seek to preserve such ‘wilderness’ from the activities of native people run the risk of reproducing the same tragedy – being forceably removed from an ancient home – that befell American Indians. Third World countries face massive environmental problems and deep social conflicts, but these are not likely to be solved by a cultural myth that encourages us to ‘preserve’ peopleless landscapes that have not existed in such places for millennia. At its worst, as environmentalists are beginning to realize, exporting American notions of wilderness in this way can become an unthinking and self-defeating form of cultural imperialism. (Cronon, 1996a: 81–2)

One way in which nature independent gets done is, then, to expel all ‘invaders’ no matter how long they have been there, and no matter that they had a role in creating this landscape in the first place. It is worth reflecting too that these people were once simply labelled as part of nature, at a time when the separate continent of nature was not thought worthy of saving. As a part of nature, the people living there were often treated as unworthy of respect, rights or political representation – a racism buttressed by naturalism. So whether part of nature or not, people living in the continent called nature have been anything but respected for their roles in ecological productions.

Figure 1.3 Rainforest as Eden, ‘La Forêt du Bresil’, Johan Moritz Rugendas

The message from Cronon and other environmental historians is clear. So-called wilderness areas are peopled, have histories and geographies, and in being so are in some way or another social as well as natural productions. In a similar vein, forested and non-forested lands on the African continent are as Fairhead and Leach (1998) have demonstrated, similarly peopled, and are in fact co-produced landscapes, landscapes where people have had a hand in developing the characteristic flora and fauna. Likewise, wild animals living in Kenya, so often visited by western tourists in search of the wonder and spectacle of nature-independent, are in some sense there on account of cohabitation with people (Thompson, 2002; Western et al., 1994). The list could be extended, but the point is made that what might look natural or wild to a western metropolitan eye is already mixed up with human worlds. To think otherwise and thereby to act otherwise (see Box 1.1) is to potentially do great damage to those people and to the landscapes, plants and animals that they have helped to make (and that have helped to make them).

Box 1.1 Thinking and acting

There’s an unfortunate tendency to imagine that thinking and acting are either unrelated or only related in certain ways. In the first case, it is common to say that actions speak louder than words. We also often say that people think one thing but often do another. And the power of thought is weak compared to the power of bulldozers. Thinking seems harmless enough, compared, for example, to the violence that can be done with other tools. The phrase ‘sticks and stones can hurt me but names never will’ is something that many learn as a means to cope with the evil thoughts of others that in the end, we are taught, matter little. But as any child knows, names and thoughts are incredibly powerful and hurtful (a matter that feminist literary theorists like Judith Butler (1997) have usefully demonstrated). Thought matters, and can have effects. So thinking and acting are related. The way we think has repercussions. It follows that the way we think about something or represent a thing or an issue often shapes the way we enact it. If I think that wilderness is a people-less space, then I might feel the need to keep it that way. On the other hand, if historians convince me that this has not been the case, then I might think of ways to enact different kinds of wilderness, ones where people cohabit with wildlife. So thinking and acting are related to one another and it is not useful to make a hard and fast distinction between thought and action. An important adjunct to this argument is that even while this is often accepted, we still tend to assume that thinking and action ar...

Figure 1.1 Nature as independent state (threatened by invasion). Nature and Society are separate spaces, but Nature is about to be or has been engulfed by Society.

Figure 1.1 Nature as independent state (threatened by invasion). Nature and Society are separate spaces, but Nature is about to be or has been engulfed by Society. Figure 1.2 Nature as dependent state. Nature is but one of many categories that emerge from and exist within the realm of human actions and orderings. It is therefore dependent on and not prior to social relations.

Figure 1.2 Nature as dependent state. Nature is but one of many categories that emerge from and exist within the realm of human actions and orderings. It is therefore dependent on and not prior to social relations.