![]()

Chapter 1 Lesson design for learning in English

Objectives of this chapter:

- To consider the thought process behind lesson preparation

- To present a distinction between lesson planning and lesson design

- To assist you in developing challenging and precise learning objectives

- To help you understand how precise objectives relate to lesson activities and pupils’ progress in learning

Introduction

This chapter has a relationship with everything that follows in this book. It is about designing lessons and preparation for teaching. It looks at the skills you need to put together lessons in which pupils learn and make progress in English, and at the related thinking and decision-making that contributes to success in the classroom. The phrase ‘lesson design’ is used very deliberately as an alternative to ‘lesson planning’. The latter phrase, the more commonly used, suggests a schedule of activities that you work through with a class during a lesson. While deciding on a sensible sequence of engaging activity is an important dimension of preparing for teaching, a focus on these aspects alone doesn’t quite capture everything that you do. Somewhere in your deliberation you may have in mind an ethos for your teaching, some guiding values and principles that may be tacit in your eventual lesson content. There will also be aspects of presentation to consider where aesthetic choices have some influence on pupils’ learning, for instance in how you design a supporting worksheet, or the arrangement of PowerPoint slides. The nature of the school timetable framing your work will have an impact on the rhythm of your teaching: some of you will work in schools where 45-minute lessons impel urgency, some of you will work in 60-minute sessions, and others will teach lessons of around 90 minutes duration which could afford different opportunities for combining two or more phases affording depth of engagement.

Not one of these items is specific to English or the pupils you teach. You will also have to take care in establishing what dimension of English merits emphasis in the immediate lesson and must often take additional responsibility for selecting the material suited to your aim. It sounds more straightforward than it is. In almost any subject in the curriculum pupils are asked to read, write, speak and listen during lessons. Clearly this is true of English, presenting teachers of the subject with opportunities and a very specific dilemma. On one hand, it means you can find connections between those different skills that have potential to be rich and enjoyable for pupils. On the other, your success as a teacher in supporting pupils’ progress can often depend on how precise you are in identifying the particular skills you want pupils to develop in the lesson being prepared. Given that pupils will use many and diverse language skills in each English lesson, isolating and emphasising the most relevant ones can be challenging. The problem is most obvious in literary study. The emphasis is usually on pupils’ responses to text and thus developing their reading skills. However, these skills are often demonstrated through writing, for example in formal assignments or creative pieces written from the perspective of a central character. The skills pupils need to write in either of these forms are very different from one another, and different too from the reading skills the pieces are intended to capture.

Finally, your design of lessons responds to the pupils that you work with on a weekly basis, having their own interests and enthusiasms as individuals and with their unique dynamics collectively in class groups. You will introduce items in one way rather than another because you know it will particularly help one pupil to grasp the topic, or use an analogy because you realise it resonates with what you know most of a class watch on TV, with the music they listen to or the sports that interest them. Some of this will happen spontaneously during teaching, but often it will be strategic too, resulting from choice, an element in a design. And the way you shape your lessons, including the space you give pupils for independent work, will reflect your concept of ‘a pupil’ – what they can do, the boundaries within which they work and the nature of their relationship with their teacher and with the subject.

The influence of the curriculum on lesson design

The information you draw on to decide what to teach will vary depending on the department you are working in, the age and level of the class and where you are in the stages of your teacher education. If you are in a first placement in the first term of your training course, you could find yourself devising lessons one at a time, probably with the guidance of a mentor or the usual class teacher. They might indicate to you the precise content and skills each lesson needs to address. In other situations, you will have access to contextual information and more responsibility and choice for deciding what pupils need to learn and how to approach it. This supporting information is likely to be in the form of a ‘scheme of work’, an overview for teaching the topic in hand, signalling the expected outcomes, activities and assessments that typically comprise this unit and often archived with supporting resources too. In some departments you may be given work booklets, worksheets and PowerPoint presentations that you are expected to incorporate into your own lessons.

The information provided by your department is likely to be connected to the most recent version of the National Curriculum (Key Stage 3: DfE, 2013; Key Stage 4: DfE, 2014a), though since its publication some schools have had greater freedom in their relationship with this according to their status. Academies and free schools are not obliged to follow it but instead have scope to devise their own curriculum for English as they do for other subjects. In schools that belong to a chain (a group of academy schools connected either locally or nationally) you may find the English department working to a curriculum shared by the whole group. Some organisations have appointed curriculum advisors with the role of designing and implementing their bespoke curriculum across each school in the chain.

Each curricular framework, whether the National Curriculum or an in-house system, will indicate the skills pupils are expected to develop in English and the content to be addressed. In English this often entails stipulating the experience pupils should have with respect to language use, knowledge of grammar, and literary texts and approaches to them.

We will use the National Curriculum as the example framework in this chapter and throughout the book, concentrating on the skills you need to interpret and use a curricular framework so that the principles can be applied to those alternative arrangements too. Wherever you teach, you will find that as well as taking into account a curriculum, you will also need to be aware of the linked assessment framework. At Key Stage 3, between the ages of 11 and 14, this is very flexible, and all schools have the scope to assess as they see fit, providing the system works in the interests of their pupils and supports their progress in learning:

Assessment levels have now been removed and will not be replaced. Schools have the freedom to develop their own means of assessing pupils’ progress towards end of key stage expectations. (DfE, 2014b: 3)

At Key Stage 4, covering ages 14 to 16, assessment practice tends to be directed by the formal examination system, with English departments looking to the detail of GCSE specifications for guidance. The process of curriculum reform reflected this in simultaneous publication of new curricular details for Key Stage 4 and revised specifications for English and English Literature at GCSE. Specifications can derive from any one of the major examination boards relevant to England, Wales or Northern Ireland. The Ofqual website provides an up-to-date overview of participating examination boards at any given time.

Deciding what to teach in your lesson

When you come to the point of designing a lesson, you are likely to have to formulate objectives. These are usually termed ‘learning objectives’ so that emphasis falls on the development you intend to support in your pupils. These may be provided for you in your department’s scheme of work or you may need to devise them yourself to express development that has some link with the curriculum framework relevant to your setting. Wherever you teach, they can often be phrased in terms of knowledge, skills and understanding.

Lesson design: an example

Arthur has prepared a lesson around Romeo and Juliet, focused on the first act which communicates to the audience information about the protagonists as each one speaks with friends or family members. In Act 1, scene 1, Romeo speaks to Benvolio about Juliet, while in Act 1, scene 3 Juliet, the Nurse and Lady Capulet debate Juliet’s marriage to Paris.

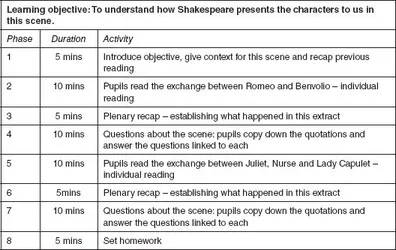

On paper, Arthur’s preparation is very much a plan in the sense of a schedule rather than a design (see Figure 1.1). It starts with an objective Arthur has devised himself, linked with the department’s Year 8 scheme of work on Shakespeare, ‘to understand how Shakespeare presents the characters to us in this scene’. When Arthur taught the lesson, it went smoothly insofar as pupils worked through the listed activities. They were compliant with Arthur’s instructions and in that respect things very literally went to plan. Even before teaching, however, it is possible to look at Arthur’s lesson details and anticipate its limited impact on pupils’ learning in terms of the stated objectives. It does not offer a coherent design because it does not describe activities or even phases to match the learning objective. The questions Arthur asks of his pupils direct them to significant details in each scene, and even to relevant information that suggests something of each character’s feelings, but no part of his plan signals that time will be spent addressing the presentation of the characters. His tutor remarked:

The steps in Arthur’s plan attend more to exploring the psychology of characters, tacitly accepting them as real people whose motives and thoughts we might explain. This is useful activity, but not what Arthur has set out to teach according to his stated objectives. You will notice too that Arthur’s lesson has a repetitive structure, with the phases of reading and questioning repeated. This may have benefit in that pupils get used to an approach to the text in the first part of the lesson and then consolidate it in the second half. However, because the tasks don’t match Arthur’s learning objective and because the questions make similar demands of pupils in each phase, the plan in this form does not convey how pupils will make progress in learning.

The objective you shared with pupils has links with the textual detail considered today but you did not address it in a way that would help pupils make progress in their understanding of presentation specifically. This aspect deserves more focused attention in your lesson design and more emphasis during teaching...