![]()

1

Introducing Action Research

Claire Taylor

This chapter will help you to:

- understand the scope of research and why it is important to engage in it

- understand specific terminology relating to research

- investigate the nature of ‘action research’ and its relevance as a tool for improving teaching and learning

- familiarise yourself with strategies to enhance further development as a reflective practitioner.

What is research?

You are probably reading this book because you have been asked to conduct a research project as part of a school initiative, or a course of further study. If you have not taken part in a formal research project before, you may be feeling a mixture of emotions: daunted, worried, excited, challenged, wondering where to start, overwhelmed. However, have you ever considered that you may already possess some of the skills necessary to engage in worthwhile research?

Education practitioners are engaged in ‘research’ as part of the routines of day-to-day work in school. Whether it be using the Internet to gather up-to-date resources for a new classroom-based project, observing a pupil to find out why certain behaviours are occurring, or analysing the latest assessments for a cohort of pupils, all of these activities constitute ‘research’. Teaching Assistants (TAs) are increasingly at the forefront of such activities and are therefore practising a wide range of research techniques – often without realising it!

Of course, there is a danger, when acknowledging that, potentially, we are all researchers, that an oversimplification of the research process may occur. It is vital that this does not happen. The issues bound up in research are varied, and the complexity of any research task must never be underestimated. It is important, though, to try to define what we mean by research, and in this respect the definition by Bartlett et al. (2001: 39) is helpful in that they describe research as ‘the systematic gathering, presenting and analysing of data’. Therefore, research uses the information-gathering practices we all use daily, but in an organised, systematic way, in order to develop theory or deal with practical problems.

Why do research…?

…to improve teaching and learning

Research in schools is becoming an accepted part of professional development, as practitioners seek to gain new insights and understanding of a wide range of school-based issues. Research is attractive as a way to build evidence-based explanations for events and phenomena. As already highlighted above, it implies a systematic approach, built upon order and organisation. More fundamentally, the expectation is for improvements in teaching and learning.

Many ‘novice’ researchers quickly develop an acute awareness of the direct benefits of engaging in research practice. For example, here are Leanne’s reflections upon the importance of research:

In the past I have successfully contributed and played an active role in research-based developments within our school, working alongside colleagues, children and parents …. As a result, I am aware of the positive impact that research can have on future developments and how it informs the raising of standards within a given subject.

All practitioners have a role to play in improving both standards and the quality of teaching and learning in school. Recent developments in school workforce reform have seen a reconsideration of ‘team working’, with teaching staff and support staff working collaboratively across the school. Therefore, a whole-team approach to evidence-based research practice has the potential to have a positive and lasting impact upon teaching and learning in a wide variety of educational settings.

…to generate new theory

While focusing on how and why educational practice can be improved is vitally important, it is not the only reason for engaging in research. McNiff and Whitehead (2005) are absolutely clear that action research in particular plays a central part in enabling teachers to be involved in the generation of theory. They go as far as to state that ‘teachers are powerful creators of theory and should be recognized as such’ (2005: 4). It seems logical to include all classroom practitioners, including TAs, within this statement, if we accept the context of a whole-team approach to evidence-based research practice as discussed above. Therefore, within the systematic and disciplined approach of a research framework, there are significant opportunities for theory generation as well as for understanding practical processes within teaching and learning.

…to facilitate the development of reflective practitioner skills

In addition to being a useful vehicle through which to spearhead improvement in teaching and learning and to generate theory, the research process is an invaluable tool for the development of reflective practice. The concept of ‘reflective practice’ within the workplace has been explored by Schon (1983; 1987) and Brockbank et al. (2002); in addition, specific work around reflective practice in educational settings has been explored by Pollard (2002) and others. This theme will be expanded later in the chapter.

Approaches to research

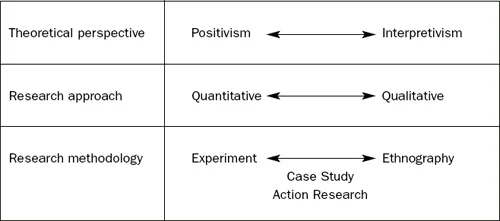

There are many different approaches to conducting research projects, and each methodological approach is situated within a theoretical perspective. Such perspectives may be represented as a continuum. At either end of the continuum are the positivist and interpretivist perspectives, and these in turn align with quantitative or qualitative research approaches, often referred to as ‘paradigms’.

Positivism

A positivist approach argues that the properties of the world can be measured through empirical, scientific observation. Any research results will be presented as facts and truths. Of course, the counter argument is that truth is not, and can never be, absolute. A positivist approach generally involves testing a hypothesis, using an experimental group and a control group. In this way, the research is viewed as measurable and objective. However, no research method is perfect and a big drawback of the positivist approach is that the research will not explain ‘why’. In addition, statistical correlations do not always equate to causality, and even controlled experiments are not immune to human contamination. However, the positivist approach has brought with it a useful legacy of sound experimental design and an insistence upon quantifiable, empirical enquiry.

Interpretivism

This stance is wholly anti-positivist and argues that the world is interpreted by those engaged with it. The perspective is aligned with a qualitative approach, with researchers concerned to understand individuals’ perceptions of the world.

Within this paradigm, researchers acknowledge that there is no single objective reality and that different versions of events are inevitable. Explanations are important and the focus is on natural settings. In addition, the research process is central, with theory developing from data after research has begun, not as the result of a predetermined hypothesis.

With each perspective comes a wealth of terminology and technical jargon, peculiar to the research world. In your reading, you may come across words such as ‘quantitative’, ‘qualitative’, ‘paradigm’ and ‘ethnographic’, to name but a few. Do not let this specialised language put you off – it has developed to enable professionals within the particular field of research to communicate with each other effectively. Sandra sums this up neatly, in her reflections upon research terminology:

Clearly, it is important to get to grips with the language used in research and to be confident that I understand all the meanings.

Action research sits within the qualitative, interpretivist perspective, but before we consider action research methodology in more depth, it will be worthwhile to summarise some other key styles of research in order to give the bigger, contextual picture of the field of research as a whole.

Experimental research

In this form of positivist, quantitative research, there is usually a hypothesis, which an experiment seeks to prove or disprove. There is an emphasis on reproducing ‘lab’ conditions in a highly structured way, and on measuring quantifiable outcomes. This approach is heavily reliant on establishing theories of cause and effect.

Case study

This is a useful approach for individuals wishing to research an aspect of a problem or issue in depth. Many education practitioners have conducted case studies investigating particular pupils. The resulting data can be rich and highly descriptive, providing an in-depth picture of a particular event, person or phenomenon. It is the richness of the account that is crucial, and Merriam (1988) is keen to emphasise that case study is more than just a description of a programme, event or process. Rather, case-study methodology is interpretive and evaluative, committed to the ‘overwhelming significance of localised experience’ (Freebody, 2003: 81).

Ethnography

This style of research was originally developed by anthropologists wishing to study cultural groups or aspects of a society in depth. The approach relies heavily upon observation and, in particular, participant observation. This sometimes demanded complete immersion in the social group that was being studied, in order to fully understand and appreciate the events taking place.

In summary, research projects may be conducted by various different approaches, aligned to certain theoretical perspectives, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1

What is action research?

‘Action research is a powerful tool for change and improvement at the local level’ (Cohen et al., 2000: 226).

Essentially, action research is practical, cyclical and problem-solving in nature. Research is seen as a fundamental way in which to effect change. When viewed in this way, the action researcher really is operating at the chalk face and is actively involved in the research process as an ‘agent of change’ (Gray, 2004: 374).

‘Often, action researchers are professional practitioners who use action research methodology as a means of researching into and changing their own professional practice’ (Gray, 2004: 392).

The focus for an action-research project is often highly local in nature. Therefore, it is unlikely that research results could be generalised to other settings; rather, the action-research project is concerned with effecting change locally, in situ. To this effect, the action-research model has wide-ranging applications and can be carried out by individuals or groups, situated within a class, department, school or cluster of schools. Cohen et al. (2000) suggest an impressive list of possible applications in educational settings, such as changing learning and teaching methods; modifying pupils’ behaviour, attitudes and value systems; or increasin...