![]()

1

Foundations of health activism

Activism

Activism is action on behalf of a cause, action that goes beyond what is conventional or routine (Martin, 2007). What constitutes activism depends therefore on what is ‘conventional’ as any action is relative to others used by individuals, groups and organisations in society. For example, where free speech is respected and protected, posting an email complaining about the government is a routine occurrence. But in an oppressive political system such an action might be seen as subversive and punishable. Likewise, singing in a choir is not activism, but singing as a protest, for example in a prison, can be. Activist actions must therefore go beyond conventional behaviour. However, in practice, organisations employ a combination of both conventional and unconventional strategies and actions to achieve their goals. In systems of representative government, conventional actions include election campaigning, voting, advocacy and lobbying politicians. Organisations that use these types of actions are not (and do not consider themselves as) activists because they operate using conventional actions. The circumstances under which activists are willing to use unconventional tactics, whilst others are not, are discussed in this book.

Human rights are central to the manifestos of many political parties. Civil, political, social and cultural human rights such as the freedom of speech and expression, privacy and the right to health, are also fundamental principles in many activist organisations. Activism and conventional politics can therefore operate side-by-side, for example, union activities alongside a Labour Party or environmental movements alongside a Green Party. Activism can be viewed from the local to the global. Local activism is often about protecting the quality of life of a community, such as when residents campaign for better local services or against the location of an industrial development (Strong, 1998). Activism within a country mostly focuses on issues affecting a nation but there is an increasing orientation toward issues crossing national borders at a global level. Local and global forms of activism can be mutually supportive, for example, community opposition to a factory assists, and is assisted by, an environmentalist agenda (Martin, 2007).

Activism has an explicit purpose to help to empower others and this is embodied in actions that are typically energetic, passionate, innovative, and committed. Activism has played a major role in protecting workers from exploitation, protecting the environment, promoting equality for women and opposing racism. However, activism is not necessarily always for a positive cause as the actions of minority groups can oppose human rights and the beliefs of others. To some, an activist is a freedom fighter, to others he/she may be a protagonist, troublemaker, vandal or terrorist. Activists are pragmatic and tend to draw on whatever information is useful for their immediate practical purposes; they want information about a situation and what is effective for dealing with it. Involvement in an activist organisation can begin by attending a public meeting and then by gradually becoming more engaged. Other people become heavily involved in the organisation very quickly but drop out due to other commitments. It is difficult to maintain a high level of involvement, especially as many activists are volunteers and may have a full-time job and a family. Some sorts of activism such as attending a vigil can last for weeks and are difficult for those with other commitments to attend. One of the challenging tasks for organisations is to develop campaigns that allow many people to participate, not just those who have the free time to be able to do so. Someone working on a campaign might spend time listening to the news, reading and sending emails, phoning others, participating in a meeting or writing a grant proposal. ‘Frontline action’ in which people are participating in support work, usually behind the scenes, is an essential part of what makes activist actions possible. Those involved in behind-the-scenes work, in support of a cause, may call themselves activists, supporters or members of an activist group. Other people who take part may not think of themselves as activists. They are simply doing what is necessary to address a pressing problem. Activist groups run training sessions for their members, but most learning occurs on a person-to-person basis, through direct instruction and learning by doing (Martin, 2007). This can be supplemented by online resources that are freely available on subjects such as community organising, campaigning, and fund raising (Fitzroy Legal Service Inc, 2012). Alternatively, activist organisations may issue their own materials such as general purpose booklets for newly recruited members involved in the campaign on how to organise themselves, where to get information, how to protest, where to find local health care and how to deal with authorities including arrests and police harassment.

Strategies for activism

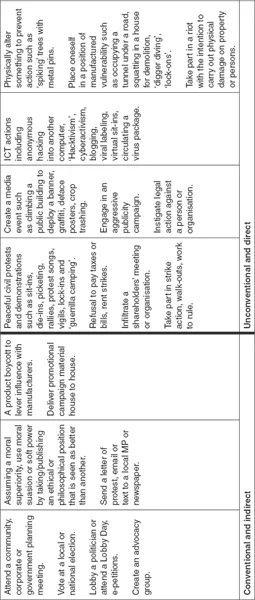

The types of actions that activist organisations engage in can be broadly subdivided into two categories: indirect and direct actions.

- Indirect actions are non-violent and conventional and often require a minimum of effort although collectively they can have a dramatic effect. Indirect actions include voting, signing a petition, taking part in a ‘virtual (online) sit-in’ and sending a letter or email to a person or organisation to protest your cause.

- For most activists, their focus is on short-term, reactive, direct tactics as their primary, and often only, means of action. Direct actions can become progressively more ‘unconventional’, from peaceful protests to inflicting intentional physical damage to persons and property. Direct action is a form of activity that aims to have a real-time and immediate effect, such as the stopping of work at a construction site that may have broader consequences for people in positions of authority or on future agenda setting.

Direct actions can be further sub-divided into: non-violent and violent actions.

| 2.1 | Non-violent direct actions include protests, picketing, vigils, marches, rent strikes, product boycotts, withdrawing bank deposits, publicity campaigns and taking legal action. |

| 2.2 | Direct violent actions include physical tactics against people or property, placing oneself in a position of manufactured vulnerability to prevent action such as ‘digger diving’, squatting in a house detailed for demolition or taking part in a civil disobedience involving the damage of personal property. |

Direct action can be symbolic and challenging, sending a message to the general public, and/or to the owners, shareholders, and employees of a specific company, and/or to policymakers, about specific grievances and threats. For example, engaging in direct action that blockaded the roads around the G8 summit in Scotland in 2005 was an example of symbolic direct action, drawing the world’s attention to the high levels of anger felt by the anti-globalisation movement. Even though the protests were relatively successful in terms of the amount of disruption to the summit they caused, such direct action would not by itself solve the problems of globalisation, but it did succeed in drawing attention to the key issues (Plows, 2007).

Some organisations use a dual strategic approach: one which is moderate and conventional whilst also using unconventional and more radical tactics. The radical strategy is carried out by individuals or covert affinity groups, ‘independent’ of the organisation, whilst the conventional tactics form the ‘official’ actions of the organisation. In practice the dynamics of this relationship are often unclear. However, a strategy that employs both conventional tactics such as lobbying and unconventional tactics such as publicity stunts, can have a dramatic influence on public opinion. The environmentalist movement Greenpeace and Code Pink, an international organisation dedicated to uniting women against violence (Code Pink, 2012), have used this approach. The risk is that the unconventional tactics can result in negative publicity and impact on future resource allocation and recruitment to the organisation. Some organisations do not accept donations from governments or corporations and depend instead on contributions from individuals and the assistance from volunteers in order to maintain an independent agenda. The balance between individual autonomy and group responsibility, and the relative importance of means and ends, are therefore often points of contention in using conventional and increasingly violent actions. Tactics vary from country to country and from organisation to organisation and the autonomy exercised by activists and their non-hierarchical structure makes a dual strategic approach both a viable and an attractive option (Martin, 2007).

The range of tactics used by activists can be explained as a dynamic continuum (see Figure 1.1) that progresses from conventional, peaceful tactics to increasingly unconventional, illegal and more violent actions. Some organisations, those that do not fall within the definition of activism, remain on the left-hand side of the continuum and use only conventional tactics. Other organisations, groups and individuals are willing to progress further along the right-hand side of the continuum to engage in unconventional tactics that are disruptive and violent. The continuum is dynamic because organisations can use a variety of tactics that move up and down the continuum, culturally informed and to some extent shaped by local laws. If the use of conventional tactics by an organisation is not successful then it may choose to use more radical tactics further along the continuum as a part of their overall strategy.

Health activism

Health activism is a combination of two key concepts: activism (discussed above) and health. But what do we mean by ‘health’? There are many different ways to define and interpret health, each of them leading to different strategies to improve and to gain more control over its determinants. Health’s many definitions include the World Health Organization’s classic: ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity’ (World Health Organization, 1948); and the Ottawa Charter’s emphasis on it being: ‘a resource for everyday life’ (World Health Organization, 1986); to the extended Bangkok Charter’s qualification of it as; ‘a determinant of quality of life … encompassing mental and spiritual well-being’ (World Health Organisation, 2005). The important elements of the concept of health that we might take from these definitions are: (1) perception and meaning (health is as much what is experienced as what can be measured), (2) social relations (health is embedded in human networks and interactions), (3) capacities/capabilities (health is a product of many intrinsic and extrinsic resources) and (4) physical functioning (health is embodied and not simply imagined) (Laverack, 2009).

Official definitions of health can differ significantly from lay definitions but both are ideal types and in practice coexist and inform one another. Practitioners have embraced a discourse that uses an official definition that goes beyond health care and lifestyle to feelings of well-being. Health is considered to be a means to an end that can be expressed in functional terms as a resource which permits people to lead an individually, socially and economically productive life. However, in practice, public health programming has increasingly been concerned with accountability to funders, effectiveness and value for money (Boutilier, 1993). Budgetary constraints and competition for funding priorities have also had a strong influence on the way in which health has been interpreted. The public health profession has taken the pragmatic view that whatever interpretation of health is used, it must be measurable and accountable, otherwise programmes employing its ideology and strategies will risk being unable to justify their economic and quantifiable effectiveness. This being the case, the measurement of health has focused on the bio-medical approach that is concerned with demonstrating a relationship between a health status measure and a behaviour such as smoking or a condition such as morbidity and mortality. The boundaries for practice and discourse have consequently been defined by the interpretations of illness and disease rather than by the way in which most people generally view their own health.

Figure 1.1 Continuum of activist actions

The bio-medical model evolved as a result of scientific discoveries and technological advances in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and this led to a greater understanding of the structure and functioning of the human body. As knowledge and understanding increased, health took on an increasingly mechanistic meaning. The body was viewed as a machine that needed to be repaired. A professional split between the body and mind developed, the body and its physical illnesses were the responsibility of physicians while psychologists and psychiatrists looked after the psyche and its abnormalities. However, the focus remained on the external causes of ill health and was reinforced by the constant threat of disease and death from epidemics such as polio and scarlet fever (Laverack, 2009). The biomedical era continued to dominate until the 1960s and 1970s, when the growing costs of publicly funded health care collided with one of capitalism’s cyclical crises of too much supply, too little demand and a declining rate of profit. This led to market pressures on the state to lessen taxation and liberalise the economy, which in turn fuelled government interest to find ways to reduce the fiscal pressure of rising medical care costs. At the same time, the ‘epidemiological transition’ in high-income countries was complete: few infectious diseases remained as threats and chronic degenerative illnesses (heart disease, cancer, autoimmune disorders) had become the major causes of morbidity and mortality. These chronic diseases involve the interplay of different behavioural risk factors over time such as smoking, lack of exercise and a poor diet, and have become synonymous with a ‘healthy lifestyle’. The search for genetic explanation had yet to commence and few were discussing the role poverty or hazardous environments played in creating disease. Health education to modify unhealthy behaviours became the principal public health intervention, slowly expanding to a broader policy focus to influence the economic and cultural forces that pattern unhealthy behaviours. As with the biomedical approach, however, there was little room for concerns with empowerment and activism and the tendency of practice was to focus on individuals in ways that became victim-blaming (Labonté and Penfold, 1981). The confluence of state interests in medical cost containment, the rise of chronic disease with more scope for prevention and the emergence of powerful new social movements (feminism, environmentalism, the New Left, civil rights), nonetheless created fertile ground for a ‘new’ public health embrace of ‘old’ public health activism.

Peter Aggleton (1991), a commentator on public health issues, divides the official interpretations of health into two main types: those which define health negatively, and those which adopt a more positive stance. There are two main ways of viewing health negatively. The first equates with the absence of disease or bodily abnormality, the second with the absence of illness or the feelings of anxiety, pain or distress that may or may not accompany the disease. Aggleton points to the importance of recognising that some people may be diseased without knowing it. People are unaware of their illnesses until they start to suffer pain and discomfort, when the person is said to be ill. Negative definitions of health emphasise the absence of disease or illness and are the basis for the medical model. A number of problems have been raised concerning the negative definition of health. In particular, the notion of pathology implies that certain universal ‘norms’ exist against which an individual can be assessed when making a judgment as to whether or not they are healthy. This assumes that such standards actually exist in human anatomy and physiology. The way in which people interpret the meaning of their own health is a personal and sometimes unique experience. Health is a subjective concept and its interpretation is relative to the environment and culture in which people find themselves. Health can mean different things to different people. Many people define health in functional terms by their ability to carry out certain roles and responsibilities rather than the absence of disease. People may be willing to bear the discomfort and pain of an illness because it does not outweigh the inconvenience, loss of control or financial cost of having the condition treated (Laverack, 2009). But on a day-to-day basis most people are not concerned if their health is perfect and instead are concerned with the trade-offs they have to make in order to live their lives. Cohen and Henderson (1991) cite examples of people who are diseased or ill and yet still perceive themselves as being healthy and willing to bear the discomfort and pain of an illness because it does not outweigh the inconvenience, loss of control or financial cost of having the condition treated. People are willing to make certain ‘trade-offs’ such as leading a stressful lifestyle, doing less exercise, smoking or drinking alcohol, in deciding what they need, or want to do, to live life but at the same time experience being healthy. However, there are situations in which people feel that even given their own personal ‘trade-offs’ that they are prevented from leading a healthy life because of, for example, the lack of opportunity or an injustice.

People may be sure about what they want but are often less certain about the means to achieve it, especially how to gain access to political influence and resources. Under such situations, people are motivated to empower themselves in order to achieve what they need and want. To become empowered involves a process by which people gain more control over the decisions and resources that influence their lives and health. Community empowerment builds from the individual to the group to a wider collective and embodies the intention, as does health activism, to bring about social, political and economic change for improvements in peoples’ lives. Empowerment and health activism also share the same sense of struggle and liberation that is bound in the process of gaining power. Power cannot be given but must be gained or seized by those who want it from those wh...