![]()

PART I

PEACE THEORY

1

Peace Studies: an Epistemological Basis

1.1 A Point of Departure: Peace by Peaceful Means

To start with, two compatible definitions of peace:

- Peace is the absence/reduction of violence of all kinds.

- Peace is nonviolent and creative conflict transformation.

For both definitions the following holds:

- Peace work is work to reduce violence by peaceful means.

- Peace studies is the study of the conditions of peace work.

The first definition is violence-oriented; peace being its negation. To know about peace we have to know about violence.

The second definition is conflict-oriented; peace is the context for conflicts to unfold nonviolently and creatively. To know about peace we have to know about conflict and how conflicts can be transformed, both nonviolently and creatively. Obviously this latter definition is more dynamic than the former.

Both definitions focus on human beings in a social setting. This makes peace studies a social science, and more particularly an applied social science, with an explicit value-orientation.

Epistemologically, peace studies will share some assumptions with all scientific endeavors, some with other social sciences, and some with other applied sciences such as medical (health) studies, architecture, and engineering.

Thus, peace studies follows such general rules for scientific research as intersubjective communicability and acceptability. Premises (data, values, theories), conclusions, and links between them must be open to public scrutiny. Science and idiosyncracy do not go together. Nor do science and secrecy, as in security studies protected by the ‘confidential: stamp. Science is public.

1.2 A Tripartite Division of Peace Studies

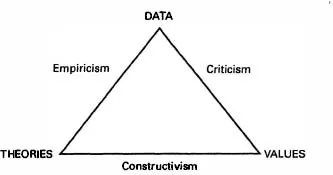

A suitable point of departure is the distinction between three branches of peace studies.1

- Empirical peace studies, based on empiricism: the systematic comparison of theories with empirical reality (data), revising the theories if they do not agree with the data-data being stronger than theory.

- Critical peace studies, based on criticism, the systematic comparison of empirical reality (data) with values, trying, in words and/or in action, to change reality if it does not agree with the values – values being stronger than data.

- Constructive peace studies, based on constructivism: the systematic comparison of theories with values, trying to adjust theories to values, producing visions of a new reality – values being stronger than theory.

Broadly speaking, these are peace studies in the past, present, and future tenses, or modes, respectively. In the logic of empiricism, data prevail over theory; in the logic of criticism, values prevail over data; and in the logic of constructivism, the (transitive) conclusion is drawn from this: values prevail over theories. Thus, in peace studies the values lumped together under the heading of ‘peace’ have the upper hand, directing the construction of the theories used to account for data. Yet the data also have the upper hand, since theories are used to account for them.

How can they both have ‘the upper hand’? Because peace studies, like any other applied science, is based on the conviction that the world is changeable, malleable, at least up to a certain point. How this adds up to an epistemology for applied science will be explored below.

Empirical peace studies will inform us about patterns and conditions for peace/violence in the past, since only the past can yield data. The canons of research are the same as for other social sciences: careful data collection, processing, and analysis, and inductive theory formation; or the other way round, deductively, comparing data and theories, adjusting the latter to the former to get consonance between data and theory.

Much can be learned from this, particularly about the past. But the (positivist) assumption that what held in the past also holds in the future is a dramatic assumption, presupposing that social phenomena have time homogeneity, with no major changes, continuous or discontinuous (ruptures) through time. Continuous changes can be predicted through extrapolation, particularly if they are monotonic, with never-waxing or never-waning trends. Discontinuous changes are more problematic. Could people in the Roman Empire have understood the ‘Middle Ages’, manorial or feudal phases; could medieval people understand the ‘Modern Period’; indeed, do we understand ‘Post-Modernity’? Futures transcending past experiences, available through empirical studies, are unknown and possibly unknowable. They are sui generis, of a new kind. History – societies or persons – does make ‘quantum leaps’, like physical nature. And so, according to evolution theory, does biological nature.

The conceptual and other tools needed to conceive of the future are not necessarily found in a research tool-chest adjusted to the present and the past, although a macro-historical overview may help. This is an argument for understanding the future through non-scientific means, dreams and myths, intuition, with artists and mystics the better scientists. More imaginative.

Critical peace studies would evaluate data or information about the present in general, and present policies in particular, in the light of peace/violence values. Such comparisons may conclude with consonance or dissonance (agreement or disagreement). In the latter case, the conclusion is not the empiricist ‘the theories/values were false’, but the criticist ‘reality is bad/wrong’, as in literary criticism or in (penal) jurisprudence. Dissonance is no reason to change values, but it is the reason to change reality so that future data may show consonance. Critical peace studies, like art criticism, should not necessarily lead to negative conclusions, even if the word ‘criticism’ is often thus interpreted. Applaudable policies can and should be applauded. Defendants are at times acquitted. But law rarely offers praise, and criticism rarely concludes ‘neither good, nor bad’.

Constructive peace studies takes theories about what might work and brings them together with values about what ought to work; this is what architects and engineers are doing, coming up with new habitats and constructions in general. If they had been empiricists only, they would have been content with empirical studies of caves and of the carrying capacity for human beings; if they had been criticists only, they would have been content with declarations deploring the shortcomings of caves and humans. Constructivism transcends what empiricism reveals, and offers constructive proposals. Criticism is an indispensable bridge between the two. There has to be motivation, anchored in values.

Empirical peace studies is mainstream social science. When applied to international relations, for instance, the result is just that: the field of ‘international relations’.2 Critical peace studies takes explicit stands. What makes it research is the explicitness not only of data but also of values, specifying what is good/right and bad/wrong, how and why. Very often this will have to be done with reference to the future: what looks like a plausible policy today may turn out to be disastrous; what looks unacceptable today may work in the longer run.

A prognosis is added, with all its uncertainties. And constructive peace studies adds to this a dimension of therapy or remedy, producing blueprints for the future – visions, images. The prognosticist gambles on a bad prognosis as a self-denying prophecy, a therapist on the self-fulfilling nature of a therapeutic vision as prophecy. Both transcend empiricism as a way of defining epistemological borders, defended by some and broken through by others. But that does not mean that every single piece of peace studies has to end up with explicit policy implications. Solid empirical peace studies is indispensable. But this is not the final product: only the beginning of a complex process, much more difficult than empirical studies alone.

1.3 Trilateral Science: the Data-Theories-Values Triangle

The three approaches build on each other because of the inner connections in the data-theories-values triangle (see Figure 1.1). Data divide the world into observed and unobserved; theories into foreseen (meaning ‘accounted for by the theory’, which may or may not imply an element of prediction) and unforeseen; and values divide the world into desired and rejected. The logic of empiricism is to adjust theories so that the observed becomes foreseen and the unforeseen unobserved. The logic of criticism is to adjust reality so that the future will produce data with the observed being the desired and the rejected being unobserved. And the logic of constructivism is to come up with new theories, adjusted to values so that the desired is foreseen and the rejected unforeseen. There is nothing new in this: medical people, architects, and engineers have been doing this for generations, centuries.

Figure 1.1 The Data–Theories–Values Triangle

If the observed is foreseen and desired, and the unobserved is unforeseen and rejected, then we live in the best of all worlds. The second-best is a world where the desired is unobserved but foreseen through an evolutionary process with some automaticity, like ‘we are condemned to peace’ in the longer run. Both of which are unlikely.

The other six combinations have built-in dissonance, with the empiricist trying to resolve the foreseen/unobserved and unforeseen/observed dissonances, and the criticist calling attention to the observed/rejected and the unobserved/desired dissonances. The constructivist tries to create a new reality by adjusting the three to each other. The point of departure is the desired/unforeseen or rejected/foreseen dissonances; this calls for new theories to make the desirable foreseeable.

Sooner or later, however, the proof of the pudding is in the eating: the foreseen also has to be observed. It is one thing to foresee, ‘image’, UN Peacekeeping Forces (UNPKF), with hand-weapons essentially as symbols of authority, combining two desirables, no violence and peace-keeping. Another is whether it works, i.e. is observed in reality.

For this it is useful to recall the distinction between empirical reality, already there in past and/or present; potential reality, to come about in the future; and irreality, never possible. Applied science explores empirical reality for ideas about a potential, and presumably better, reality. The cognitive bridge is a theory open enough to foresee the unobserved, not a closed system accounting only for an already observed empirical reality. And the bridge is composed of the values defining steep gradients between the rejected and the desired, with the persistent question, ‘But could it not work in the future?’ This is a meaningless question in a world assumed to be unchanging or to run according to unchanging laws – which is how we have been taught to think about the physical world, but not about biological, social, and personal worlds.

The ultimate test can be found only in the logic of empiricism, where data have the final say. But since reality is not final but created all the time (a Buddhist/humanist rather than a Christian/physicist assumption3), there is always a new approach, a new reality, new data, in an everlasting process. The negation of that process – insisting that the desired potential can never be empirical, e.g., ‘because violence is inherent in human nature’, or that the desired potential has by definition already been realized ‘because we are revolutionary/had a revolution’ – that is known as dogmatism.

Although this spiral process can be started at any point in the triangle and work in any direction, one frequent point of departure is the observed/foreseen/rejected dissonance. Something empirical is well accounted for, ‘explained’, theoretically. But it is also ‘bad’, to put it in simple terms – like war. This is where imagination has to enter the process. To account for the empirical also calls for that commodity. But to account for the non-existing or not-yet-existing calls for even more, since there is no empirical reality to be inspired by or to latch onto.

What is often done is to locate some tiny empirical reality in the remote corners of society, history, and geography, and then explore the conditions for its existence (including the conditions for its non-existence if it vanished), attempting generalizations.4 Another, more promising, approach is to explore a fully fledged empirical reality that is isomorphic, structurally similar, to the potential reality one hopes to bring about, like deriving hypotheses about peace from healthy life.

1.4 Science as Invariance-Seeking and – Breaking Activity

One formula for breaking through the wall which theories have built around empirical...