![]()

ONE

Asking Questions and Individual Interviews

This chapter introduces:

- Question and answer sequences: closed and open questions and follow-up questions or probes.

- Structure in interviews.

- Forms of interviewing, including phenomenological, ethnographic, feminist, oral and life history, and dialogic interviewing.

In the film Surname Viet, Given Name Nam, Trinh T. Minh-ha (1989) purposefully upsets our assumptions about interviewing by juxtaposing English-language interviews of Vietnamese women that at first look to be real, against interviews conducted in Vietnamese with English subtitles of – we find out as the film unfolds – authentic interviews of people who have acted the parts of the interviews we have seen earlier in the film. In a further twist, we find out that Trinh has translated transcriptions of interviews from a Vietnamese book to form the basis of the scripts for interviews of the Vietnamese women who introduce the film with their touching, evocative, and sometimes heart-rending narratives. In but one of the themes explored in this film, Trinh cleverly asks questions of both the interview as method, and how researchers translate the voices of others into visual, oral, and written texts.

In this chapter, I begin my exploration of the interview as a research method by first examining ‘questions’ and ‘answers’ as a basic conversational sequence. Second, I discuss different structures for interviewing, including structured, semi-structured, and unstructured interviews. Third, I review a variety of approaches to individual interviewing practice used by qualitative researchers. In contemporary qualitative research practice, there are numerous forms for conducting individual interviews as well as labels to characterize them. These include semi-structured, unstructured, and structured interviews; formal and informal interviews; long, creative, open-ended, depth, and in-depth interviews; life history, oral history, and biographic interviews; feminist interviews; ethnographic interviews; phenomenological interviews; and dialogical, conversational, and epistemic interviews. And this is by no means an exhaustive list! The purpose of reviewing a variety of approaches to interviewing is to assist researchers to make sense of the labels used in the methodological literature. Researchers may then select the kind of interview structure and form that is both consistent with their theoretical assumptions, and appropriate to generate data to answer research questions.

An Introduction to Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative interviews may be conducted individually or in groups; face-to-face, via telephone, or online via synchronous or asynchronous computer mediated interaction. In this book, I focus on qualitative interviews in which an interviewer generates talk with an interviewee or interviewees for the purposes of eliciting spoken, rather than written data to examine research problems (for those interested in learning about synchronous and asynchronous online interviews, see Beck, 2005; Davis et al., 2004; Egan et al., 2006; Hamilton and Bowers, 2006; James, 2007; James and Busher, 2006).

Information concerning the design and conduct of structured interviews or standardized surveys is not the focus of this book, since the purpose of these interviews – often administered via telephone – is to generate responses that may be coded to a fixed set of categories, and analyzed quantitatively. Much research has investigated the standardized survey methodologically (Houtkoop-Steenstra, 2000; Maynard et al., 2002; Schaeffer and Maynard, 2002; Suchman and Jordan, 1990); and advice is also plentiful with respect to construction and administering of surveys and questionnaires (see for example, Brenner, 1985; Foddy, 1993; Genovese, 2004). Interestingly, many suggestions for conducting an effective survey interview are reiterated in recommendations for conducting ‘good’ qualitative interviews.

The term interviews is used to encompass many forms of talk – including professional interviews such as counseling and therapeutic interviews, job interviews, journalistic interviews, and so forth. What all of these forms of talk have in common is that parties are engaged in asking and answering questions. Whatever the structure or format of an interview, or medium used for an interview (such as telephone, face-to-face, or computer-mediated), the basic unit of interaction is the question–answer sequence. Given that researchers pose questions to participants with the aim of eliciting answers, it is useful to examine in more detail how ‘closed’ and ‘open’ questions work, and how they can generate different kinds of responses.

Questions and Answers

Questions are particular kinds of statements that request a reply – although posing a question does not necessarily mean an answer will be forthcoming, or that the answer will relate to the particular question posed. In his analysis of conversation, sociologist Harvey Sacks (1992) located a class of utterances that he labeled ‘adjacency pairs’ (see Appendix 2 for a glossary of terms used in conversation analysis). In an adjacency pair, when a first-pair part (in this case, question) has been uttered, it sets up the expectancy that a second-pair part (an answer) will be forthcoming. Interviews are built on the assumption that questions asked by the interviewer will be followed by answers provided by the interviewee. Two kinds of questions that are routinely used in interviews are closed and open questions.

Closed Questions

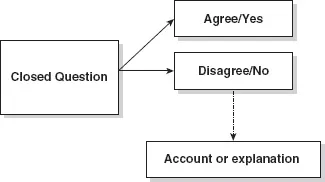

Understanding questions is simple – isn’t it? Maybe not. Although we immediately recognize or understand when a question has been posed in interaction, how to ask interview questions that are comprehended by others and answered in ways that generate relevant data is more complex than initially apparent. Some question structures have been found to have a certain kind of preference for the response. That is, response types might be marked or unmarked for certain kinds of adjacency pairs. For example, invitations prefer acceptances, and declinations are typically followed by accounts, or are ‘marked.’ Self-deprecations prefer disagreements, whereas agreements present an interactional difficulty to be negotiated by speakers. The question beginning this section is posed as an assertion with a tag, ‘isn’t it?’ This question formulation implies a particular kind of response, which, in this case is confirmation (‘yes’). The response that follows the statement above is the ‘dispreferred’ response, or disagreement. Researchers have found that dispreferred responses (such as when an invitation is declined) are usually followed by accounts, or explanations (as demonstrated in this paragraph). Although this closed question is formulated as an assertion that implies confirmation, the response generated is neither yes nor no! Thus, we can express something about the format of this particular question–answer sequence as shown in Figure 1.1 below. Note that that dotted arrow from the dis-preferred response to the account or explanation indicates that a speaker may provide an explanation, although this does not always occur.

Figure 1.1 A closed question and possible ways of responding

Many methodological texts advise qualitative interviewers to ask open, rather than closed questions because closed questions have the possibility of generating short one-word answers corresponding with yes/no or factual information implied by the question (for example, What time is it? One fifteen). Thus, closed questions are those in which the implied response is restricted in some way. For example, the closed question I posed below is answered by a single-word affirmation from the participant:

Excerpt 1.11

| Interviewer (IR) | And, do you have choruses at school yourself? |

| Interviewee (IE) | Uh-huh. |

Interviewees may respond to closed questions as if they were open by providing further description. For example, in response to the following probe that I posed as a closed question, the interviewee in Excerpt 1.2 provided further explanation, rather than supplying a one-word affirmation such as ‘yes.’

Excerpt 1.2

| IR | Now you mentioned that you started taking private lessons yourself. Had you had formal music training prior to that? |

| IE | At a very early age, my father had enrolled me in a piano class. And I begged him to let me drop out. And he said, ‘Well the only way I’ll let you drop out is if you play a sport.’ So I started playing soccer, so that I would not have to play the piano. |

| IR: | Huh. |

| IE: | That was probably the dumbest decision that either one of us ever made. |

In Excerpt 1.2, we see that even closed questions can generate significant explanation, rather than simple yes/no responses. Thus, while closed questions may imply yes/no responses – they are not always taken up in that way. Yet, it is a wise move for novice interviewers seeking to generate in-depth descriptions of people’s perceptions and experiences to learn how to pose open, rather than closed questions. This should not be taken to mean that there is no place for closed questions in a qualitative interview. In Excerpt 1.2, a closed question is used as a follow up question to clarify an aspect of a preceding narrative that was not central to the research topic. Therefore, closed questions can also be used judiciously by qualitative interviewers to clarify their understanding of details provided by interviewees.

Open Questions

Open questions are those that provide broad parameters within which interviewees can formulate answers in their own words concerning topics specified by the interviewer. Questions beginning ‘Tell me about …’ invite interviewees to tell a story, and can generate detailed descriptions about topics of interest to the interviewer. These descriptions can be further explored when the interviewer follows up on what has already been said by asking further open-ended follow up questions, or ‘probes’ that incorporate the interviewee’s words. For example, I have used the following kinds of questions in interviewing to clarify topics, and elicit further description:

You mentioned that you had ______; could you tell me more about that.

You mentioned when you were doing ____, _____ happened. Could you give me a specific example of that?

Thinking back to that time, what was that like for you?

You mentioned earlier that you _____. Could you describe in detail what happened?

Probes frequently use the participant’s own words to generate questions that elicit further description. This is an important point, because in everyday conversation, we regularly use ‘formulations’ of what others have said to us to clarify our understanding of prior interactions. There is a distinct difference between using formulations to sum up our understanding of others’ talk and using the participants’ words to generate questions. In the former, interviewers use their own terms to sum up what they have heard (through a process of preserving, deleting, and transforming aspects of what has already been said, see Heritage and Watson [1979] and Appendix 2 for further information). By formulating talk, interviewers are likely to introduce words into the conversation that the participants themselves may not use. Just as in everyday conversation, interviewees may take up the researcher’s terms at a later point in the talk – in effect recycling what the interviewer has said rather than selecting their own words. This is avoided when interviewers use the participants’ words to generate probes. In Excerpt 1.3, we see in an interview that I conducted how I formulated talk in a way that my research participant commented on.

Excerpt 1.3

| IR | Yeah, so the, like the identification of the vocal timbre. |

| IE | Right. |

| IR | Gets identified with sexual orientation. |

| IE | Exactly. |

| IR | Yeah. |

| IE | Look at you. Putting that into big words, you know. |

In this example, I formulated the interviewee’s previous talk concerning how she had overheard comments from fifth-grade boys that boys who sang sounded gay as ‘the identification of the vocal timbre gets identified with sexual orientation.’ In this instance, the interviewee commented on how this formulation had transformed her comments into ‘big words.’ Here I elicited agreement to my formulation from the interviewee; however, another way of approaching this talk could have been to generate more detail concerning the interviewee’s response. There are many probes using the participant’s words that could have been used, however, perhaps the simplest probe is: tell me more about that.

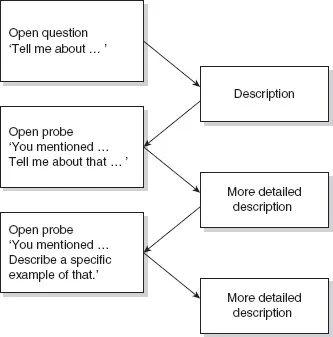

When asking open ended questions, interviewers need to be sure that the topic is sufficiently specific so that the interviewee will be able to respond. If topics have not been explained, or are unclear to interviewees, they may have difficulty in answering broad open-ended questions. When interviewees and interviewers both feel comfortable talking to one another, it can take as few as four or five key interview questions with appropriate probes to generate talk of an hour or more. A possible sequence of open questions can be illustrated diagrammatically (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 An open question and possible ways of responding

‘Structure’ and Interview Talk

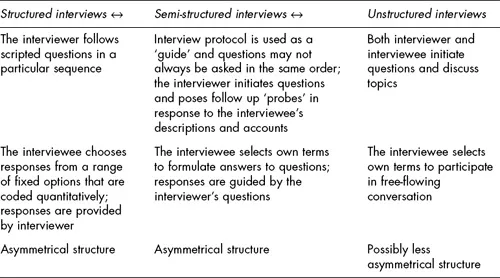

Broadly speaking, research interviews for the purposes of social research range across a spectrum from structured, tightly scripted interviews in which interviewers pose closed questions worded in particular ways in specific sequences, to open-ended, loosely guided interviews that have little or no pre-planned structure in terms of what questions and topics are discussed (see Table 1.1).

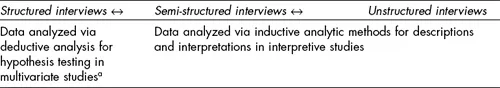

Table 1.1 Range of interviews

Note: aAlford (1998: 38) explains that multivariate arguments attempt to measure factors that explain a ‘particular social phenomenon’, while ‘interpretive’ arguments are those that ‘combine an empirical focus on the language and gestures of human interactions with a theoretical concern with their symbolic meanings and how the ongoing social order is negotiated and maintained’ (1998: 42). Interpretive arguments may also ‘focus on ideologies, discourses, cultural frameworks’ (1998: 42).

Respondents of structured interviews are called upon to select their answer from those listed by the interviewer (see Foddy [1993] and Fontana and Prokos [2007] for more detail on structured interviews). Interview researchers using a standardized format of interview are advised not to deviate from the script, although conversation analytic studies of talk generated in standardized survey interviews suggest that this is technically very difficult to do, given that interviewees may not understand questions, and speakers may demonstrate a variety of other interactional difficulties in the administration of survey instruments (see, for example, Houtkoop-Steenstra, 2000; Houtkoop-Steenstra...