![]()

CHAPTER ONE

WHAT IS ‘DEVELOPMENT’?

‘Development’ is a concept which is contested both theoretically and politically, and is inherently both complex and ambiguous … … Recently [it] has taken on the limited meaning of the practice of development agencies, especially in aiming at reducing poverty and the Millennium Development Goals. (Thomas, 2004: 1, 2)

The vision of the liberation of people and peoples, which animated development practice in the 1950s and 1960s has thus been replaced by a vision of the liberalization of economies. The goal of structural transformation has been replaced with the goal of spatial integration.… … The dynamics of long-term transformations of economies and societies [has] slipped from view and attention was placed on short-term growth and re-establishing financial balances. The shift to ahistorical performance assessment can be interpreted as a form of the post-modernization of development policy analysis. (Gore, 2000: 794–5)

Post-modern approaches… see [poverty and development] as socially constructed and embedded within certain economic epistemes which value some assets over others. By revealing the situatedness of such interpretations of economy and poverty, post-modern approaches look for alternative value systems so that the poor are not stigmatized and their spiritual and cultural ‘assets’ are recognized. (Hickey and Mohan, 2003: 38)

One of the confusions, common through development literature, is between development as immanent and unintentional process… … and development as an intentional activity. (Cowen and Shenton, 1998: 50)

If development means good change, questions arise about what is good and what sort of change matters… Any development agenda is value-laden… … not to consider good things to do is a tacit surrender to… fatalism. Perhaps the right course is for each of us to reflect, articulate and share our own ideas… accepting them as provisional and fallible. (Chambers, 2004: iii, 1–2)

Since [development] depend[s] on values and on alternative conceptions of the good life, there is no uniform or unique answer. (Kanbur, 2006: 5)

1.1. INTRODUCTION

What is the focus of ‘Development Studies’ (DS)?1 What exactly are we interested in? In this first chapter we discuss perhaps the fundamental question for DS: namely – what is ‘development’? Following Bevan’s approach (2006: 7–12), which has been outlined in our Introduction, this is the first ‘knowledge foundation’ or ‘the focus or domain of study’.

In this chapter we discuss the opening quotations to this chapter in order to ‘set the scene’. The writers who have been cited are, of course, not unique in addressing the meaning of development, but the selections have been made in order to introduce the reader to the wide range of perspectives which exists.

It would be an understatement to say that the definition of ‘development’ has been controversial and unstable over time. As Thomas (2004: 1) argues, development is ‘contested, … complex, and ambiguous’. Gore (2000: 794–5) notes that in the 1950s and 1960s a ‘vision of the liberation of people and peoples’ dominated, based on ‘structural transformation’. This perception has tended to ‘slip from view’ for many contributors to the development literature. A second perspective is the definition embraced by international development donor agencies that Thomas notes. This is a definition of development which is directly related to the achievement of poverty reduction and of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

There is a third perspective from a group of writers that Hickey and Mohan (2003: 38) broadly identify as ‘post-modernists’.2 The ‘post-modern’ position is that ‘development’ is a ‘discourse’ (a set of ideas) that actually shapes and frames ‘reality’ and power relations. It does this because the ‘discourse’ values certain things over others. For example, those who do not have economic assets are viewed as ‘inferior’ from a materialistic viewpoint. In terms of ‘real development’ there might be a new ‘discourse’ based on ‘alternative value systems’ which place a much higher value on spiritual or cultural assets, and within which those without significant economic assets would be regarded as having significant wealth.

There is, not surprisingly, considerable confusion over the wide range of divergent conceptualizations, as Cowen and Shenton (1998: 50) argue. They differentiate between immanent (unintentional or underlying processes of) development such as the development of capitalism, and imminent (intentional or ‘willed’) development such as the deliberate process to ‘develop’ the ‘Third World’ which began after World War II as much of it emerged from colonization.

A common theme within most definitions is that ‘development’ encompasses ‘change’ in a variety of aspects of the human condition. Indeed, one of the simplest definitions of ‘development’ is probably Chambers’ (2004: iii, 2–3) notion of ‘good change’, although this raises all sorts of questions about what is ‘good’ and what sort of ‘change’ matters (as Chambers acknowledges), about the role of values, and whether ‘bad change’ is also viewed as a form of development.

Although the theme of ‘change’ may be overriding, what constitutes ‘good change’ is bound to be contested as Kanbur (2006: 5) states, because ‘there is no uniform or unique answer’. Views that may be prevalent in one part of the development community are not necessarily shared by other parts of that community, or in society more widely.

In this chapter we discuss these issues and we seek to accommodate the diversity of meanings and interpretations of ‘development’. In Section 2 we critically review differing definitions of ‘development’. In Section 3 we ask what different definitions mean for the scope of DS (i.e. what is a ‘developing’ country). Section 4 then turns to indicators of ‘development’ with Section 5 summarizing the content of the chapter.

1.2. WHAT IS ‘DEVELOPMENT’?

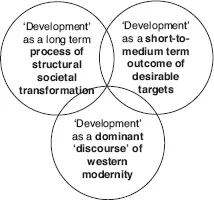

In this section we set up three propositions about the meaning of ‘development’ (see Figure 1.1). It is inevitable that some members of the development community will dismiss one or more of these, while others will argue strongly in favour. Even within individually contested conceptualizations there is space for considerable diversity of views, and differing schools of thought also tend to overlap. This overall multiplicity of definitional debates includes a general agreement on the view that ‘development’ encompasses continuous ‘change’ in a variety of aspects of human society. The dimensions of development are extremely diverse, including economic, social, political, legal and institutional structures, technology in various forms (including the physical or natural sciences, engineering and communications), the environment, religion, the arts and culture. Some readers may even feel that this broad view is too restricted in its scope. Indeed, one might be forgiven for feeling that ‘there is just too much to know now (as, indeed, there always was)’ (Corbridge, 1995: x).

We would argue that there are three discernable definitions of ‘development’ (see Figure 1.1). The first is historical and long term and arguably relatively value free – ‘development’ as a process of change. The second is policy related and evaluative or indicator led, is based on value judgements, and has short- to medium-term time horizons – development as the MDGs, for example. The third is post-modernist, drawing attention to the ethnocentric and ideologically loaded Western conceptions of ‘development’ and raising the possibilities of alternative conceptions.

Figure 1.1 What is ‘Development’?

1.2a. ‘Development’ as a long-term process of structural societal transformation

The first conceptualization is that ‘development’ is a process of structural societal change. Thomas (2000, 2004) refers to this meaning of development as ‘a process of historical change’. This view, of ‘structural transformation’ and ‘long-term transformations of economies and societies’, as Gore noted, is one that predominated in the 1950s and 1960s in particular. Today, one might argue that this definition of development is emphasized by the academic or research part of the development community but that there is less emphasis on this perspective in the practitioner part of the development community (as has already been broached in our Introduction).

The key characteristics of this perspective are that it is focused on processes of structural societal change, it is historical and it has a long-term outlook. This means that a major societal shift in one dimension, for example from a rural or agriculture-based society to an urban or industrial-based society (what is sometimes called the shift from ‘traditional’ to ‘modern’ characteristics), would also have radical implications in another dimension, such as societal structural changes in the respective positions of classes and groups within the relations of production for example (by which we mean the relationship between the owners of capital and labour). This means that development involves changes to socio-economic structures – including ownership, the organization of production, technology, the institutional structure and laws.3

In this conceptualization development relates to a wide view of diverse socioeconomic changes. The process does not relate to any particular set of objectives and so is not necessarily prescriptive. Equally, it does not base its analysis on any expectations that all societies will follow approximately the same development process.

All countries change over time, and generally experience economic growth and societal change. This process has occurred over the centuries, and might be generally accepted as ‘development’ in the context of this discussion. This perspective on development is not necessarily related to intentional or ‘good’ change. Indeed, in some cases development involves decline, crisis and other problematical situations – but all of this can be accommodated within this wide perspective of socio-economic change.

Despite its generally non-prescriptive nature this approach has a strong resonance with the ‘meta-narratives’ (meaning overriding theories of societal change – refer to Chapter 4 for a more detailed treatment) that dominated DS during the Cold War. These were grand visions of societal transformation – either desirable transformation as modernization, or desirable transformation as a process of emancipation from underdevelopment. These are different perspectives which, generally, sought to prescribe their own one common pathway to an industrial society for newly independent countries. Although these meta-narratives have a strong resonance with the definition of development as structural societal change, they were deemed to be unsatisfactory in explanatory power in the late 1980s. Hickey and Mohan (2003: 4) argue that the failure of this approach to development theory is one reason why there has been a shift away from defining development as being coterminous with structural change.

Hickey and Mohan (2003) take the view that the pressure on international development research to be relevant has undermined this older established definition in favour of a more instrumental one (a fuller discussion of this issue appears in Chapter 2). A long-te...