![]()

SECTION 1

Everyday Memory

![]()

1

Memory for People: Integration of Face, Voice, Name, and Biographical Information

Bennett L. Schwartz

From the day we are born, we are immersed in a world with other people, both familiar and unfamiliar. Thus, the ability to recognize and remember other people is and has been critical to human beings and is likely to have played a role in the evolution of human cognition (Adachi, Chou, & Hampton, 2009; Macguinness & Newell, 2014). In this chapter, I review the data on memory for people: for their faces, their voices, their individual characteristics, and their names. This research comes from a variety of perspectives: cognitive neuroscience research, everyday memory, evolutionary psychology, neuropsychology, perception research, and traditional experimental psychology. The goal here is to synthesize this research into a coherent whole. Is there some common representation for individual people, for example, that binds together our memory of their faces, their voices, their names, their history, and their characteristics? These latter questions have only been partially addressed, but an attempt will be made to answer them here.

One of the crucial distinctions in memory for people is the distinction between familiar people and new or unfamiliar people (see Bahrick, 1984; Johnston & Edmonds, 2009, for a review). Familiar people include those we know personally and those we know vicariously, such as athletes, celebrities, and politicians. Unfamiliar people are those we have just seen for the first time. In fact, it is a continuum, ranging from the highly familiar (e.g., a close family member) to the somewhat familiar (a casual acquaintance at work) to the unfamiliar (someone who just passed you on the street of a large city). Following Johnston and Edmonds (2009), it is the current hypothesis that we use different mechanisms to discriminate among familiar people than to recognize facial and other characteristics of new people. From a functional perspective, this is important. We have a history with familiar people, for good or bad. That is, we know we can trust our mother, but we know we cannot trust our boss. This comes about from many interactions with these people as individuals. Therefore, we must be able to recognize these people quickly and accurately. New or unfamiliar people may represent promise or threat. They must be learned quickly and added to the system that represents people. Therefore, for familiar people, the focus will be on models of representation and retrieval. For unfamiliar people, the focus will be on models of encoding (Johnston & Edmonds, 2009). Of course, recognizing unfamiliar people is important in one highly studied area of memory, namely eyewitness memory. Other chapters in this volume will address eyewitness memory, so I will mostly leave that topic for others.

BRIEF HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Historically, memory for people has been divided into separate areas. There are researchers who study face memory (Bruce, Henderson, Newman, & Burton, 2001), a small number of researchers who study voice memory (Mullennix, Ross, Smith, Kuykendall, Conard, & Barb, 2011), researchers who study memory of people’s personal characteristics (Kole & Healy, 2011), and researchers who study memory for names (Evrard, 2002). However, recently, there have been attempts to integrate the research into a common approach based on memory for individual people (e.g., Hanley & Cohen, 2008; O’Mahoney & Newell, 2012). As Hanley and Cohen discuss, memory for people is not like memory for other objects. In most cases, we do not have to recognize individual objects – a hammer is a hammer, a water glass is a water glass. Rather we must simply recognize an item as being part of a class of objects. Of course, we may have a favorite pen, a favorite mug, or a favorite wrench, but these are the exceptions, not the rule. However, in almost all cases, we must recognize individual people as individual people, and not as an exemplar of a particular category of people. Again, there may be exceptions, such as an athlete need not recognize an individual opponent, but rather just recognize him or her as being part of the other team. Indeed, Yovel, Halsband, Pelleg, Farkash, and Gal (2012) found that neonatology nurses were no better at identifying individual newborns than were control participants because such nurses seldom need to focus on faces of infants as individuals (parents will take comfort in those identity bracelets). But in most contexts, we do need to do so. Our first line of person recognition is their facial appearance. So much of this review will focus on faces, rather than other aspects of “personhood.” But the point remains – people must be recognized as individuals not as part of a class of objects.

Memory for faces has been of interest to psychology for a long time, particularly from the perspective of eyewitness memory (Münsterberg, 1908). Earwitness memory, however, is a much more recent interest (Clifford, 1980; Yarmey, Yarmey, & Yarmey, 1994). Witness memory is most often interested in a specific set of circumstances – a brief encounter, under stress, with a stranger. However important to legal circumstances, such memory is not the norm for people as they live their lives. More often, we must recognize well-known faces of family, friends, or work colleagues, or we must remember the names of casual acquaintances based on well-lit exposure to their faces and adequate hearing of their voices. Professors, for example, are occasionally greeted by former students in restaurants, bookstores, and other places. Unlike the eyewitness situation, this is a brief encounter with a familiar person, which does not occur during a stressful situation. Do we recognize these people and can we remember their names?

Another important historical development in memory for persons is the seminal model of face memory of Bruce and Young (1986). They were interested in how we represent familiar faces in long-term memory (see Figure 1.1). The model postulates a module known as the face recognition unit (FRU). FRUs are specialized devices designed to quickly and accurately assess whether a face is familiar or not. FRUs are connected to Person Identity Nodes (PINs). PINs are the central memory representations for individual people, containing information about the person’s relation to the perceiver, his or her occupation, nationality, and other such biographic information. Important in the Bruce and Young model is that names are stored separately, in another node (the Name code node). It is the independent representation of name information that creates the situation in which we can recognize a familiar person, know quite a bit about them, but not be able to recall their name (e.g., Hanley & Chapman, 2008). Bruce and Young’s model was influential in face memory research and continues to direct research today (Hanley & Cohen, 2008; Schweinberger & Burton, 2011).

Figure 1.1 A simplified version of the face recognition model developed by Bruce and Young (1986).

Another important historical research trend comes from neuropsychological research on prosopagnosia, or face agnosia (Bauer, 1984). Prosopagnosia represents a neurological condition in which only face recognition is impaired, but other forms of visual object recognition are intact. In reality, such “pure” patients are rare for any neuropsychological profile. Research on prosopagnosia has focused on whether or not there is a special neural mechanism for recognizing faces that is different from recognizing other objects (Tanaka & Farah, 1993). If so, we would expect an occasional patient to show a relatively “pure” pattern. Research on prosopagnosia and recent neuroimaging studies suggests that there are unique neural mechanisms in the human cortex that are responsible for the recognition of familiar faces, as some prosopagnosic patients show impairments remarkably close to the expected pattern of impaired face recognition without impairment to other forms of visual object recognition (Moscovitch & Moscovitch, 2000).

Memory for proper names has also been a topic of interest for some time (Cohen & Faulkner, 1986). Central to the study of memory for proper names is the observation that we may often forget or misremember names of people well known to us (Hanley, 2011). That is, we may recognize a person’s face and may remember factual information about them, such as their profession, but we fail to access their proper name. Indeed, face–name associations are often memories for which we have tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) experiences (Hanley, 2011; Yarmey, 1973). Thus, the oft-experienced phenomenon of being in a TOT experience for the name of a person you know well has also driven research on memory for people. At first glance, it appears that person memory is successful at integrating some forms of information (e.g., face recognition with personal knowledge), but poor at integrating other forms of information (faces with names). We will return to this issue later in the chapter.

Thus, four major trends have driven research on memory for people. They are the research on eyewitness (and earwitness) memory, the Bruce and Young (1986) model of face recognition, research on prosopagnosia, and the research on retrieval difficulties of known proper names. With these trends in mind, it is time to move to a discussion of the current theoretical and empirical debates in person memory. We start with research on face recognition.

MEMORY FOR FACES: IS FACE MEMORY SPECIAL?

Whether face recognition occurs via a special mechanism or through normal object recognition has been a debated topic for some time (Farah, Wilson, Drain, & Tanaka, 1998). Over the last ten years, however, a preponderance of the evidence now supports the contention that face memory is special – that there are specific neurocognitive mechanisms for the rapid recognition and learning of human faces as compared with other kinds of stimuli. There is an important terminological distinction here – face perception refers to the rapid identification of face stimuli as faces, whereas face recognition here refers to the identification of individuals from their faces. In this section, we will consider the evidence that supports the view that face recognition is served by a unique system. Most of this research will therefore draw on the recognition of familiar faces.

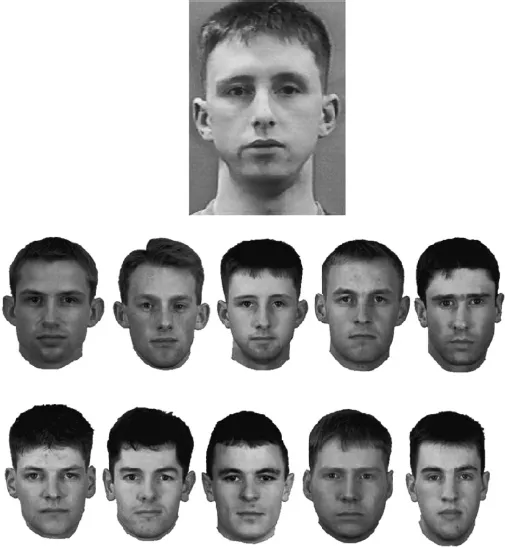

Most studies suggest that people are good at recognizing familiar faces even across various transformations whereas unfamiliar faces are quite difficult to recognize after transformation. For example, Bruck, Cavanagh, and Ceci (1991) asked participants to match college yearbook photos of classmates with the current images of those people. Despite 25 years of aging, the participants showed high accuracy in matching the 22-year-old faces with the 47-year-old faces. Hole, George, Eaves, and Razek (2002) showed that familiar faces could be recognized across a variety of computergenerated transformations, such as inversion and vertical and horizontal stretching. Moreover, people are good at recognizing familiar faces across transformations of age, hair style, camera angle, and a host of other variables, although often poor at recognizing unfamiliar faces across these transformations (Megreya & Burton, 2006) (see Figure 1.2). These findings have a number of practical implications. For example, they suggest that including photographs on identification cards may not particularly help in identifying identity thieves, as clerks and others may not be good at matching the face handing them the card with the face on the card (Kemp, Towell, & Pike, 1997).

Megreya and Burton (2006) argued that the special mechanism for face recognition is specific to familiar faces, and that unfamiliar faces are processed by normal mechanisms of object recognition (also see McKone, Kanwisher, & Duchaine, 2007). Their reasoning is based on the data with the matching of inverted faces. The inversion effect refers to the observation that people are poor at recognizing inverted (upside-down) faces relative to the inversion of common objects (Valentine, 1988; Yin, 1969). The standard explanation is that faces are matched by holistic face-specific mechanisms, which are disrupted by inversion, whereas normal object recognition is not. This has been taken as evidence that there is a specific face-specific recognition mechanism (McKone et al., 2007; Hanley & Cohen, 2008). Interestingly, Megreya and Burton found that unfamiliar faces showed less decrement in performance when the faces were inverted than when familiar faces were inverted, and that individual differences in performance with unfamiliar faces was positively correlated with performance on non-face objects, but that there was no correlation between non-face objects and familiar faces. As a consequence, Megreya and Burton argue that specific face-recognition mechanisms exist for familiar faces, but that unfamiliar faces use the same mechanisms as non-face objects.

Neuroscience research suggests that we have specialized neural mechanisms that have evolved specifically for face learning and face recognition. Neuroscientists have identified an area of the brain known as the fusiform face area (Kanwisher, McDermott, & Chun, 1997; McKone et al., 2007; Macguinness & Newell, 2014; Sergent, Ohta, & MacDonald, 1992). The fusiform face area (FFA) is located on the ventral surface of the temporal lobe, adjacent to the medial temporal lobe area. Although there is some debate as to how specific the FFA is to face recognition, most research now suggests that the area is involved in the recognition of familiar faces (and face-like objects) after an object has already been perceived as a face. That is, the FFA is an area for identifying familiar faces (Liu, Harris, & Kanwisher, 2010; Ewbank & Andrews, 2008). A separate area of the brain – the occipital face area (OFA) appears to be responsible for making the initial identification of a face as being a face, regardless of its familiarity (Liu et al., 2010) (see Figure 1.3). Thus, neuroanatomy supports the idea that there are differences between recognizing familiar and other objects. However, some research disputes that the FFA is unique to face perception; these researchers argue that the FFA is sensitive to other stimuli in addition to faces, and therefore it is inaccurate to refer to it as an area that specializes in face recognition alone (Haxby, Hoffman, & Gobbini, 2000; Minnebusch, Suchan, Köster, & Daum, 2009). Nonetheless, the bulk of the neuroimaging research points to the FFA as a distinct area for recognizing familiar faces (Liu et al., 2010).

Figure 1.2 Try to find the face among the ten below that match the face above. It is there but is surprisingly difficult to find. From Megreya and Burton (2006). Memory & Cognition. Reprinted with permission.

Neuropsychological research consistently shows that it is possible to show dissociations between deficits in face recognition (prosopagnosia) and other kinds of object recognition (object agnosia). For example, Sergent and Signoret (1992) examined a population of diagnosed prosopagnosics. They found that the prosopagnosics were superior at recognizing makes of cars than they were at identifying familiar faces. In a double-dissociation study, Moscovitch and Moscovitch (2000) examined prosopagnosic patients and patients diagnosed wit...