![]() FICTIONS OF RHYTHM

FICTIONS OF RHYTHM![]()

Beyond Meaning: Differing Fates of Some Modernist Poets’ Investments of Belief in Sounds

Natalie Gerber

In an essay entitled “The ‘Final Finding of the Ear’: Wallace Stevens’ Modernist Soundscapes,” Peter Middleton argues that “[s]ound is secondary” and noncognitive and finds Stevens’ and other modernist American poets’ investment of belief in sound to be “utopian.”1 Of course, such investment was not limited to the American modernists. The romantic poet William Wordsworth speaks of the “power in sound/ To breathe an elevated mood,”2 and fellow romantic Samuel Taylor Coleridge qualifies a legitimate poem as one that, “like the path of sound through the air,”3 carries the reader forward. Likewise, the nineteenth-century French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé aspired toward a musicalized language for poetry that would make the poet capable “not just of expressing oneself but of modulating oneself as one chooses.”4 Paul Valéry, Stevens’ contemporary, believed, as Lisa Goldfarb writes, that “the poet must perceive the primacy of sound over meaning.” 5 Hence American modernist poets like Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, and William Carlos Williams could not claim uniqueness but rather obstreperous insistence upon both the primacy of sound and its value beyond the semantic.

These poets’ willingness to believe that linguistic sound offers transparent access to our innermost thoughts, feelings, and emotions ought to be startling;6 it certainly has been challenged and problematized by scholars pointing to both the constructed and the socially, historically, and politically situated contexts that produce both the poem and the poet’s subjectivity.7 Yet cognitive research proves that rich phonological representations are activated early in our processing of silent reading;8 this so counters Peter Middleton’s assertions about the nature of sound that we should reconsider these poets’ appeal to prosody as a primary ground as perhaps not merely utopian or impressionistic, even if we recognize their statements to exaggerate the importance of sound over meaning.9 While a full correlation of psycholinguistic findings in relation to some modernist poets’ investments of belief in sound will have to wait for another essay, this one will prepare that ground by disentangling competing claims regarding sound among three particular American modernists (Stevens, Williams, and, especially, Robert Frost) and by offering a novel solution why Frost’s claims have fared worse than these contemporaries’, all of which are equally predicated upon the sound structure of a poem.

Stevens and Frost

As two preeminent American modernists writing metrical verse, Stevens and Frost might well share a limited legacy of formal innovation; and yet Stevens has been granted greater stature as a prosodic innovator and theorist. It is tempting to attribute this difference in reception to Frost’s adamant rejection of newer modes of poetic rhythm, while Stevens practices free verse alongside metrical composition. Nonetheless, the difference is more likely attributable to the specific nature of their prosodic innovations, which differ significantly in the level of phonological representation involved, a difference that matters to the reception of their legacy.

As in his well-known remark in “The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words,” Stevens’ comments about sound focus on the sounds of individual words: “Above everything else, poetry is words; and . . . words, above everything else, are, in poetry, sounds.”10 Rarely, if at all, does he speak of larger linguistic units, such as the phrase, sentence, or line. Throughout Stevens’ letters and his prose, we find statements such as “I like words to sound wrong,”11 or “A variation between the sound of words in one age and the sound of words in another age is an instance of the pressure of reality.”12

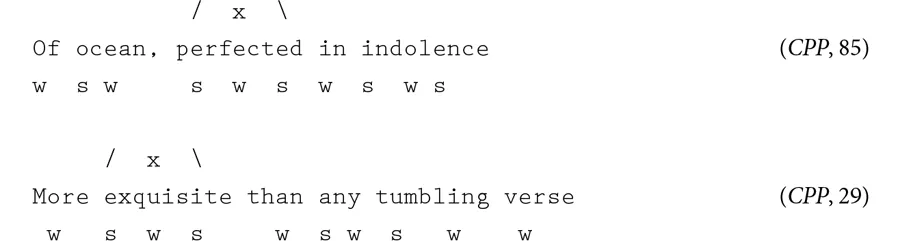

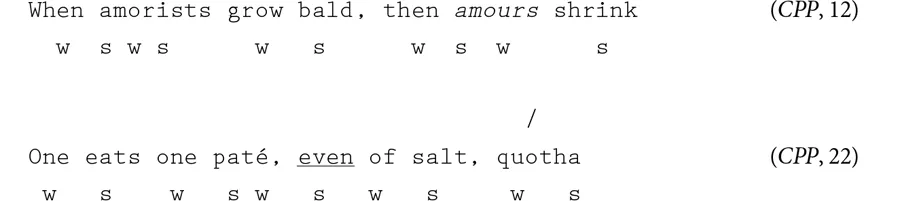

Likewise, as I have shown elsewhere,13 much of Stevens’ early and mid-career metrical innovations turn upon an inventive yet strictly rule-governed play with lexical stress, that is, with how words sound depending upon their linguistic, syntactic, and, of course, metrical environments. Stevens’ placement of words into the meter in such a way that they “sound wrong”—i.e., altered from normative realizations—displays quite a sophisticated awareness of factors influencing lexical phonology; these run the gamut from historical pronunciations and cross-linguistic difference (particularly between French and English) to quite supple realizations of English stress rules (for lexical, compound, and phrasal stress). For example, when Stevens writes,

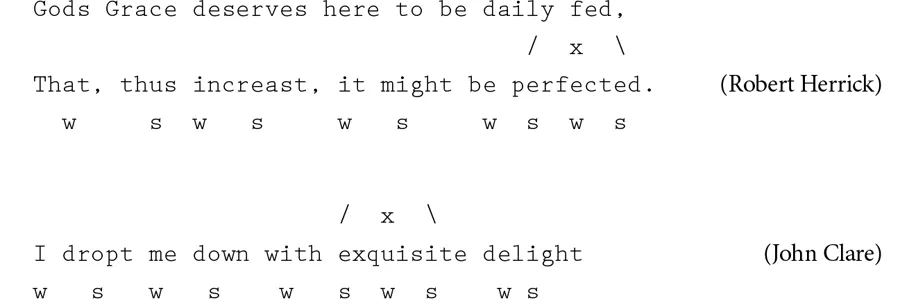

he is echoing usages of an earlier age, as in the second line of Robert Herrick’s couplet from 1647, and John Clare’s line from 1819:

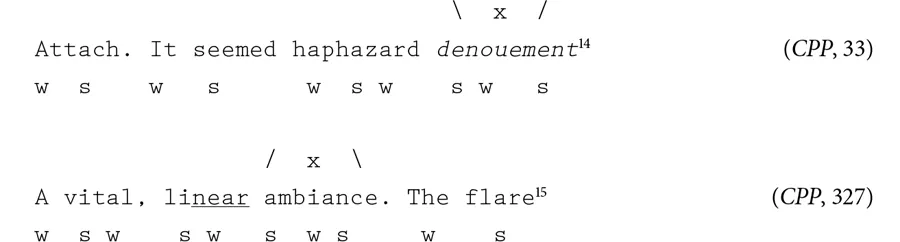

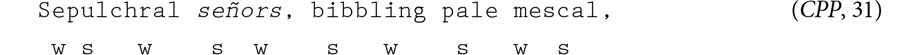

And when Stevens writes lines like those below, he is drawing on the use of French stress patterns, to motivate an alternate pronunciation:

In stark contrast, the next examples display Stevens self-consciously forcing a bungled Anglicization of a foreign word, a rhythmic tactic that contributes to the comic portraiture of the young poet:

Supple auditor of French that he is, Stevens’ use of the rhythm rule to retract stress from the second syllable of amour to the first to avoid a stress clash with shrink displays a virtuosic multilingual wit, one echoed in the prior examples.

Were these examples not enough, one could examine Stevens’ existential play with the stresslessness of nonlexical words to unmoor any certain meaning, and thus destabilize what otherwise ought to be a triumphant declaration: for example, in response to the question “What am I to believe?” in “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction,” the twelve-syllable, entirely nonlexical iambic-pentameter line “I have not but I am and as I am, I am”16 winkingly refuses our desire to impose certain iambs and shapes on belief. Or we could look to evidence in “Sea Surface Full of Clouds” of Stevens’ masterly orchestration of the full variety of circumstances that produce disyllabic words with initial stress. As the poem renders its serial, modulating impressions of the sea “In that November off Tehuantepec,” the image brought to mind shifts from “rosy” to “chop-house,” “porcelain,” “musky,” and, finally, “Chinese chocolate,” as in “And made one think of chop-house chocolate.”17 Thus, within the metrical baseline “And máde one thínk of [ / x] chócoláte,” we find activated supple rules for “‘fitting . . . a selection of the real language of man in a state of vivid sensation’” to the meter:18 these range from phonological rules governing segments (i.e., consideration of vowel length and its influence on stress [e.g., the underlying vowel length and lexical rhythm of rosy and musky are comparable to the vowel length and lexical rhythm of Mary, not Marie] and the reduction of sonorant sequences [porcelain]), to stress rules involving larger entities (e.g., compound stress [chop-house] and the rhythm rule, whose domain is the phrase [Chinese chocolate]).

In summary, we can isolate the word as a significant locus of Stevens’ innovative metrical effects, discerning how his virtuosic meter intensifies our awareness of the variable rhythms that come from words’ shifting relationships in linguistic context, grammar, syntax, and metrical placement.

In contrast with this exacting play with words by Stevens, Robert Frost treats words as plastic elements within larger compositional units, rather than individual lexical entities. Frost once remarked, “The strain of rhyming is less since I came to see words as phrase-ends to countless phrases just as the syllables ly, ing, and ation are word-ends to countless words.”19 Clearly, Frost came to regard words, for poetic purposes, as functionally equivalent to morphological adjuncts in language—they may be essential, but they are not the base.

That base, for Frost, lies in larger prosodic units like phrases and, especially, sentences, which Frost presents as the domain generative of meaning: “I shall show the sentence sound saying all that the sentence conveys with little or no help from the meaning of the words.”20 Indeed, when Frost speaks of words, he speaks of them as “other sounds” that may be strung upon the sentence sound, suggesting that, for him, sentence sound is primary: “A sentence is a sound in itself on which other sounds called words may be strung.”21

As we might expect then, unlike Stevens, Frost rarely invites us to attend to individual words, to modulations in their stress accents or even finer adjustments in linguistic rhythm occasioned by their changing syntactic functions or metrical placement. Instead, Frost invites us to hear the possible shifts in either the nature or location of melodic accent—a higher-level accent that falls across sequences of words and reflects a speaker’s or reader’s sense of what holds the greatest informational, contextual, or emotional value.

Frost’s acclaimed “Home Burial” exemplifies how his scaffolding of speech rhythms within the metrical template focuses attention on the intonational contours (that is, both on the possible locations of the tonic syllable and the potential for shifts in pitch height and direction on the tonic) and thus on the range of interpretive stances associated with the characters’ statements. Its opening lines, with multiple possibilities for melodic accent,22 mirror the poem’s subject matter—a mobile and latently violent power struggle between the husband and wife. Whether we place melodic accent on either or both members of the contrastive gender pair (he and her, she and him) or upon the preposition before makes a tremendous difference to our interpretation of the poem’s unfolding drama: “He saw her from the bottom of the stairs / Before she saw him.”23 That all of these decisions are enabled by the poem’s metrical rhythm, a muted blank verse, means that readers must struggle with decisions regarding melodic emphasis as essentially matters of interpretation. The multivalent possibilities for pitch height and direction on the phrase “before she saw him” are essentially inferential: any single prosodic change also involves meaning....