![]()

Chapter 1

CHAM AND DAUMIER

Parallel Careers, Diverging Reputations, Complementary Audiences

Bowing to the Great Name Market, I was tempted, for a moment, to call this book “Cham: The Disciple (Rival?) of Daumier.” I soon decided that this would be unfair to both Cham and Töpffer, Cham’s enduring first master. Yet my ambition remains to carve into the dominant “Daumier Market.” This chapter is a first step on this route.

Cham and Daumier, whose lives overlapped so closely, offer a clear contrast in style, critical appraisal, and posthumous reputation. The major comparisons at the time, however, greatly favored Daumier. In Champfleury’s Histoire de la Caricature Moderne (1865), Daumier is half the book, Cham not even mentioned; the same is more or less true of Baudelaire’s writings.

Daumier gained stature as one of the great, virtually mythic painters of his age, who happened to earn his living as a highly productive and much enjoyed journal lithographer. His best satirical lithographs were raised from the journals as “art prints” printed on good paper, hung on the wall, and incorporated into special private and museum collections, some of them aspiring to completeness.

Cham, on the other hand, was always seen as a mere caricaturist. He was (and is still) quite unknown as a painter (cf. Fig. 4.1, chapter 4), and never sought or was granted the status of real artist. Did anyone at the time (apart from the dépôt légal and the French national library) seriously collect Cham? As far as we know, during his lifetime, only his father did. Today, we find emerging a few enthusiasts who have begun the daunting task of compiling his work.

Daumier aimed to produce striking images, single or few figures filling a full page of the daily Charivari, images effective independently of the captions. Daumier tended to disown the text of the captions (or others did so on his behalf), probably because he seldom invented them himself. Cham, by contrast, devised all his own captions, which carry the joke, and give point to the drawing. He developed a specialty in groups of small vignettes, often as many as twelve to a page, focused on a particular theme or the minutiae of day-to-day sociopolitical gossip. His picture stories were for the most part also composed of small vignettes.

Daumier, who scarcely ever attempted narrative (just twice, under editorial duress), and who worked on a much larger scale, was committed to creating lasting social types and depicting pregnant social situations. Whether drawn small or large, Cham’s characters seem more ephemeral, as are his jokes—bound to the moment, the place, the verbal witticism. Cham’s creations, especially when in small album format, allowed for a quick reading and casting away, as opposed to the lingering and repeated gaze that Daumier invited, and posterity has given. At Daumier you looked, admired, smiled; at Cham you laughed, chuckled, smiled, the pleasure of a moment—as we might today at any magazine cartoon.

The audience was different too. Daumier, like Gavarni, appealed to the upper-middle-class segment, the art connoisseurs among Le Charivari’s politicized, culturally aware public; Cham spoke to the lower-middle, less art-conscious class, the curious who relished fun made of the scandal or little folly of the moment. Cham was the chronicler of the fleeting moment, where Daumier wanted to catch the permanence of the human condition. The cultural elite knew this: a critic and poet such as Baudelaire compared Daumier to Michelangelo, and important novelists including Balzac and Banville, and even caricature historian Champfleury, all of whom had upper-class connections, had no time for Cham.

Economically dependent on his regular lithographs for Le Charivari, Daumier eventually became tired, overextended, with an output that appears to us immense: four thousand prints, but in fact a number surpassed by Gavarni and Doré, and even more so by Cham, who produced so many drawings that no one has been able to count them. When Daumier at last took a prolonged (three-year) leave from Le Charivari, more or less willingly, to dedicate himself to painting, Cham, whose output had long outstripped Daumier, was easily able to fill the gap.

Quite apart from his huge contribution to Le Charivari and other magazines, Cham’s audience was certainly bigger, as is attested by the number, variety, affordability, and popularity of his little albums. He also reached a major class of reader normally less drawn to Daumier: children and adolescents. Can Cham justifiably be called the most successful as well as the most prolific and popular caricaturist of what is often called the “age of Daumier?” Some facts and numbers may answer this question.

Cham’s name must have been far more widely known during the last thirty years of his life (and Daumier’s). Despite the critical attention that Daumier garnered during his final years for his paintings, prints, and exhibitions of both, Cham was the first to receive full-scale biographical treatment, in 1884, four years before Arsène Alexandre’s biography of Daumier. In Vapereau’s Dictionary of Contemporaries of 1880, Cham gets more space than Daumier, perhaps because his albums were more available and considerably cheaper than Daumier’s. The pre-1956 National Union Catalog (NUC) of American libraries has nearly 160 entries for Cham dated or datable to the nineteenth century, ten times more than entries for Daumier in the same period.

By the first half of the twentieth century, however, the reverse was true: the NUC lists not a single publication of or about Cham, as opposed to 83 for Daumier. In the NUC, Cham’s oeuvre includes no less than 123 differently titled albums (most admittedly small), exclusive of the more or less composite (factice) anthologies. The standard catalog of French prints by Jean Adhémar lists 241 items for Cham, a few of them duplications. As early as 1886, French publisher and bibliophile Henri Béraldi appealed for a catalog of Cham’s work, noting that producing one would certainly be an “intimidating” task.1 A comprehensive catalog is still lacking. However, it appears first steps have been taken, and Chamophiles can be grateful that compilation is more feasible in this age of the computer and microfiche.

Both Cham and Daumier worked primarily for the same republican, largely oppositional journal, Le Charivari. But they shared its politics unequally. Cham never divested himself of his aristocratic, legitimist-monarchist leanings, which also drew him into the opposition to all four regimes under which he lived. Daumier stands forth, among all his colleagues, as the most unbending republican, always for example, refusing the Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest decoration, instituted by Napoleon in 1802. By contrast, Cham gratefully accepted the honor, but only under the Third Republic, and very late in life. Under the Empire, we are told, it was feared Cham would decline, as Daumier and realist painter Gustave Courbet had.

From his royalist father, Cham inherited support for the “legitimist” Bourbon line, and he thus felt alienated from both King Louis-Philippe and upstart Emperor Napoleon III. Cham’s opposition to republican government revealed itself later, after 1871, but did not prevent him from continuing his collaboration with Le Charivari, despite its explicit republicanism and anticlericalism. He was one with Daumier and all caricaturists in opposing the socialists in and after 1848, as he was in his French chauvinism, and willingness to promote Louis-Napoléon’s military adventurism. He was, however, a close friend and theatrical collaborator of Henri Rochefort, also an aristocrat, who would become a communard. Like the bourgeoisie and the caricaturists generally, Cham deplored the Commune (1871) as much as the German invasion, but he took pity on and sought to help imprisoned communards. Further examination might reveal a petty-bourgeois conservative, as so many satirists are, suspicious of all the various streams in the political current, and content to swim against them all.

Cham and Balzac Maybe?

The above is intended as an alternative to the obligatory critical twinning of Daumier with Balzac. Dare one inject Cham into the dazzling critical spotlight on Balzac?

Did the great novelist ever meet the ubiquitous Cham? He must have, for there is evidence he was close to several of the leading caricaturists—but I find no mention of Cham in the Balzac literature. Yet they were both social pivots and outrageous in different ways. In their own personas, both Balzac and Cham invited personal caricature, Balzac with his famous jeweled cane, Cham with his dog and umbrella. Physically they were opposites: Cham tall, thin, aristocratic. Balzac short, fat, plebeian. Their politics were similar: clerico-monarchist, with a shared admiration for the first Napoleon Bonaparte; satirists of the status quo but content, albeit in a critical way, with modernity.

Bixiou, Balzac’s affable, witty caricaturist and practical jokester, recurrent in La Comédie Humaine, was first created in 1838, the year before Cham began his career. It’s tempting to imagine Bixiou, who, like Cham, was once a government clerk, coming alive in a real-life Cham. Perhaps it would be safer to compare Cham not to the undisputed greatest French writer of his age, but to Balzac’s friend and rival Eugène Sue, whom no one reads nowadays, but who was also excessively prolific and highly regarded in his time. Prolificity then as now was not an unmixed good; journalism encouraged it to excess, and critics grew suspicious. Call it a frenetic overproduction—of which greed, as in any industry, was a suspected motor. Or else, sheer debt and desperation driving Balzac’s close to one hundred novels and stories, encompassing 2,472 characters, 320 of them memorable enough to be mentioned in Philippe Bertier’s Daily Life in Balzac’s Human Comedy. Stack these figures against whatever demons pushed Cham to produce tens of thousands of drawings, with personages of all kinds, including those in the forty or so narratives in focus here, which offer some amusing and memorable characters. (I doubt that there is much memorability in the rest of Cham’s huge oeuvre, the thematic series, the miscellanies, or above all the Revues Comiques.)

Whether or not their superproductivity is truly comparable, Balzac and Cham are linked in a more important literary aspect: their sense of detail. Balzac, in “[his] examination of details and little facts [composed] … with the admirable patience of the old mosaic makers … that impose themselves as the absolute condition of this new society … the bric-à-brac, and the rags and tatters, the language and gesture of a porter, of an artisan, the way a worker leans against the door of his shop” (Bertier). All this in excess, for excess is a way of life, of creation, of journalism, and of the installment novels that Cham so adeptly satirized, even as he wallowed in the bric-à-brac and topical minutiae of his Revues de la Semaine.

Both Balzac and Cham are excessive journalists, Balzac obviously much more than that. He has been called the historian of his age. Is Cham this too, at a much lower level, but higher than that of a mere gossipmonger? I believe so. Unlike Balzac, Cham does not mold his social observations into a dynamic unity, but rather seems to regard the age as defying the very idea of unity—hence his Revue Comique filled with “rags and tatters” of mini-cartoons that virtually parody the self-image of the journalist as historian-reporter, engaged like the caricaturist in the retailing of trivia. Balzac in Lost Illusions has the journalist wondering, “‘what have we got for tomorrow’s issue?’ ‘Nothing.’ ‘Nothing?’ ‘Nothing!’ And yet, it must appear. And so it will: on time, piquant, mischievous, pyrotechnical.”2 A conversation one can well imagine in the offices of Le Charivari.

![]()

Chapter 2

THE JOKER IN THE PACK OF LIFE

The Gentleman

We are slowly discovering more about the life of Cham. There is only one proper biography on which I rely much here, by journalist Félix Ribeyre, a close friend of Cham. Published in 1884, just four years after Cham’s death, it is anecdotal more than analytical. I have gathered some additional journalistic and archival scraps from sources elsewhere, but I have found that extant biographical material about Cham is as thin as his physique, especially compared with available material about the other major caricaturists of the era, Grandville, Töpffer, Daumier, Gavarni, Nadar, and Doré. Fortunately, some success has attended my efforts to overcome this dearth of material: two important caches of privately owned Cham correspondence have been made available to me, which illuminate hidden corners of his family relationships.

This much about Cham is undisputed, or nearly so: he was born in 1818 in Paris into an ancient and respected aristocratic family. Although his full given name was Charles Henri Amédée de Noé, in childhood he was known as Amédée, and later by the pseudonym Cham.

Contemporary opinion that has survived agreed on two salient personal characteristics about Cham the man: he was the perfect gentleman, but also a lifelong joker. He was a lover of practical and verbal humor, addicted to playing tricks, telling jokes, and uttering torrents of witticisms and puns. Practical jokes aside, the latter are the stock in trade of caricature generally; perhaps these more genteel, less satiric forms of conversational humor allowed Cham to maintain his “gentlemanly” aristocratic demeanor and entertain his bourgeois friends. This was all the easier for him, since he lacked the overarching political convictions or passions of Daumier, Grandville, or Nadar—always excepting his hatred of communards.

Cham was the topographer of the surface, seldom aspiring to depth either in his design or in psychology. In a compilation published by conservative interests in a conservative Third Republic seeking stability, he was praised for the gaiety and humanity of his humor, versus the cynical and melancholic irony of Gavarni and the bitterness of Daumier. Cham was said to have made no personal enemies, and to have harbored no malice even when mocking public figures, like the political activist and anarchist theoretician Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. The little we know about Cham indicates that his peers saw his jokes as mostly inoffensive, but it is not clear whether this widely held view pertained to his innumerable printed cartoons, his conversational wit, or both. There appears to be general agreement that Cham was courteous as befits a gentleman, with a generosity extended to colleagues and younger aspiring artists. (We reserve to the end of this chapter a tribute to his gentlemanly character from his lifelong friend Nadar.)

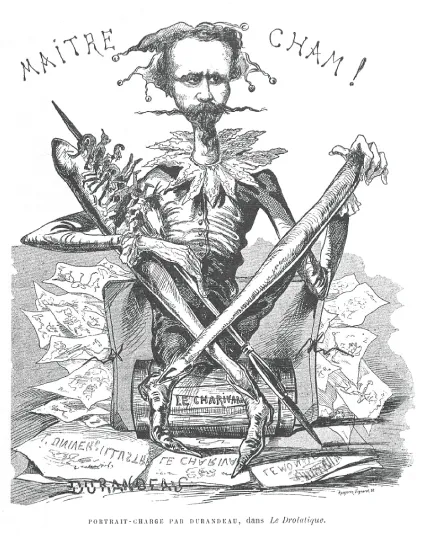

Fig. 2.1. Emile Durandeau, Maître Cham! As jester, skewering all classes. Le Drolatique. From Ribeyre.

Ideology is implicit in the emphasis on the gentlemanly: it gives us a kind of classless (or supra-class) universalizing. This is evident in the critics’ need, surviving Cham’s death, to make this aristocrat déclassé working for a republican magazine under four very different regimes appear an apolitical animal, with a friendly face to all, the court jester laughing genially at everything, with malice toward none (Fig. 2.1).

In some ways, he was “above it all”—and quite literally. Physically, he was striking. Albert Wolff, the editor of Le Charivari who knew him well in his later years, saw Cham “as tall as a drum-major, thin as an Englishman, with his cold mask, to which formidable moustaches and a long goatee beard gave a conscious military air. Cham wanders through Parisian life without bitterness or passion, laughing at everything, sk...