![]()

ONE

FROM BRITISH MUSEUM TO MUSEUM OF MANKIND

The monumental facade of the British Museum was an awe-inspiring sight when I walked through the gates on the morning of New Year’s Day in 1968. I was nineteen and going to start work as an assistant conservation officer in the Department of Ethnography. Coming from a farm on the other side of Bristol as a country boy, my new colleagues soon began to tease me as a ‘hayseed’, parodying my Somerset accent with expressions such as ‘Cor, buggerrr me!’ I had my own stereotype of them as Cockneys and I enjoyed their quick wit and urban sophistication. I soon learned that for all the grandeur of the British Museum, ‘Ethno’ was a homely and amusing place to work, as well as a source of fascinating knowledge to feed my imagination about faraway people and places. It did not occur to me that I might still be working for the British Museum fifty years later, and writing about it.

At the time I wasn’t too concerned with what ethnography meant, and nor were my colleagues. Curious acquaintances might make guesses like ‘Is it something to do with insects?’, but we accepted it as technical jargon that went with the job. I was excited to be working on artefacts from Africa, Oceania, the Americas and Asia and it was some years before I had to explain ethnography to visitors, after the Ethnography Department had become the Museum of Mankind and I was its Education Officer. Then I would say that it really meant the description of culture and, since this evidently applied to the whole of the British Museum, go on to explain that it usually covered the cultures studied by anthropology (which was hardly less ambiguous). Over the years one or two senior curators in the Department attempted to redefine ethnography as a distinctive academic methodology, and I tried to confront the unpleasant historical truth that in museums it really meant no more or less than the colonial world’s savages and barbarians or, as they were more politely called, ‘primitive cultures’.

Ethnography in the British Museum began among the ‘artificial curiosities’ of its founding collections in the mid-eighteenth century, which included items like blowgun darts from Borneo; ‘w.ch being try’d had no effect on a wounded pigeon’, and ‘A piece of flowered weaved stuffe made of grasse leaves from Angola worth there one shilling’. In the course of the nineteenth century, the Museum’s artefacts were separated from the Library and the Natural History collections, paintings were sent to the National Gallery, the Museum was rebuilt and then the artefacts were divided into Departments of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Coins and Medals, and Oriental Antiquities. Oriental included all those cultures not regarded as part of the Classical heritage of Europe, including British and Medieval, Egyptian and Assyrian, as well as Ethnography, which emerged as a kind of dustbin category for everything else. However, as the British Museum’s Handbook to the Ethnographical Collections explained in the early twentieth century: ‘the great ancient civilizations … even that of Greece, arose gradually from primitive stages of culture; the instruments and utensils of savage and barbarous peoples are therefore not without interest to the study of antiquities’ (British Museum 1910: 1). That more or less summed up what ethnography meant to the British Museum at that time.

Those who still confuse the British Museum with the Natural History Museum may like to note that the natural history collections moved to the new ‘British Museum (Natural History)’ in the 1880s. This made more room for a growing number of new acquisitions, including massive quantities of ‘ethnography’. As the British Museum continued to reorganise, the Ethnographical Collections were shifted between several new departments – British and Medieval, then Oriental, then Ceramics and Ethnography – as if the Museum didn’t quite know where they belonged – until they were given a department of their own in 1946. What ethnography meant during the latter twentieth century is shown by the things that department did not include. It covered Africa (except ancient Egypt, the ancient Greek and Roman and urban Islamic societies of north Africa, and later European and Asian immigrants); the Americas (all native peoples and ancient civilisations but not European or African immigrants); the Pacific Islands and Australia (again, indigenous peoples only); and contemporary peasant societies of Asia and eastern Europe (but not the ancient or elite cultures of the major civilisations to which most of them belonged).

When I began in 1968, no one seemed to question this institutional structure or the academic world view it represented, and I had already assimilated it from a year of voluntary work for Bristol City Museum, which had qualified me for the job at the British Museum. I had been interested in ancient history and archaeology since I was small and, after demonstrating my inaptitude for engineering during six months as a stores assistant for a tractor company, my father agreed to pay for my keep while I tried something different. An archaeology curator (and future Director of the Museum of London), Max Hebditch, happened to live in our village of Clapton-in-Gordano and he gave me a lift in and out of Bristol each day. After a couple of weeks stuffing envelopes for the Secretary of the Prehistoric Society, Egyptologist Leslie Grinsell, I began to get my hands on the collections. I helped pack the Oriental collections, which they were selling off, then redisplayed the whole Ethnography gallery, which no one else had the time or interest for. It wasn’t beyond even a beginner to improve on the jumbled displays I had gazed at in wonder as a child. There was the grimacing cut-out face added to a Plains Indian shirt and leggings, spread flat on the wall as if waving a tomahawk, under the heading ‘The American Indian at War’, and the chain of Australian boomerangs, strung from each other on wires through holes drilled in the edges. I went through the drawers underneath the tall window cabinets to discover many more marvellous objects and mounted whatever I could fit into the new display on hessian-covered backboards. Much of the remainder I was able to re-store in new wooden cabinets in the basement, with plenty of mothballs to prevent further holes in things like Waiwai feather headdresses from Guiana and red-tufted Naga ornaments from Assam.

That was how I discovered ‘ethnography’, as the works of faraway exotic peoples whose recent existence made them so much more fascinating than the threadbare past of archaeology which had interested me till then. Not only were the artefacts complete rather than just imperishable buried fragments, but there were photos and books describing the people who had made them, resonating with the colonial folklore of my upbringing. I had been an Indian in games of cowboys and Indians, with chicken feather headdress and a tipi with bamboo poles which later served for homemade bows and arrows and even an African spear. My father had all Rider Haggard’s novels of adventures in Darkest Africa and was an admirer of the adventure novelist Jack London. When I read London’s books based on a voyage to the Pacific I was fascinated by his portrayal of savage Solomon Islanders and incredulous that people could be as brutal and degraded as he described them. Just as I had questioned my Church of England primary school teaching that heathens were condemned to Hell before they had even the opportunity to choose Christian redemption, so I could not accept that ‘natives’ were ordained to be so savage and subhuman. I think my parents’ ideals of social justice led me to idealise the natural order of the world as essentially moral and they certainly encouraged me to question the Christian dogma of that school. I knew that when we were separated into the sheep and the goats on the Day of Judgement, I would be one of the goats, as a non-believer. My childhood cry of ‘But it’s not fair!’ continued to resonate long after my belief in God was destroyed by reflecting on the amorality of the natural world. Eventually I was able to refute the savage stereotype as an anthropologist who got to know these Solomon Islanders personally, but in the meantime I found beautiful Solomon Islands artefacts and read Smithsonian Institution studies of Native Americans as I burrowed through the Bristol collections.

Then I went on to work in the conservation workshop in the basement. I learned to repair and restore shattered Medieval and Roman pots (and a Roman-period skull which I accidentally dropped from a six-foot shelf), to clean corroded bronze and make resin casts of coins and stone tools, some good enough to be confused with the originals. I took the chance to clean a New Guinea over-modelled and painted skull and an Austral Islands Polynesian feather headdress. It was all this, with photos to prove it, that convinced the British Museum to employ me. But at the same time I got involved in the fun and games between the two archaeology conservators and the two taxidermists in the workshop next door, all young men. What started with water-pistol fights between the two factions soon escalated to squeezy detergent bottles. The graphic designer, who used a darkroom in the archaeology workshop for his silk-screen printing, joined in, and then they all raided the carpenters as they were fitting out a gallery upstairs. The climax came when we chained one carpenter’s bicycle to a full dustbin outside our workshops and when he inadvertently pulled the bin over, I lured his wary colleagues down the corridor to laugh at him, got on the other side of them, and we soaked them all with our squeezy bottles. Their most spectacular prank was making gunpowder from sulphur, saltpetre and iron filings, purchased on the petty cash from Boots the chemist. They never managed an explosion, but eventually an inch of the mixture in an aluminium saucepan produced a roaring column of flame which left nothing behind but the iron handle. I’m surprised no one got the sack, but Max Hebditch never even asked on our way home in his car why my hair and shirt were soaked.

So when I came to the British Museum, I was already familiar with the idea of primitive peoples, and with the secrets that the junior technical staff kept from their academic curatorial bosses, but I also became conscious of how the Museum reflected British class culture. I was prepared for this too, having been brought up between families who were bourgeois and petty aristocracy on my mother’s side and working class on my father’s. My companions at primary school were the sons of manual labourers who called my father ‘Mr Burt’ when he employed them for the haymaking, and my best friend’s father was the postman. My mother’s family had big houses and awfully posh accents and all stood up when someone entered the drawing room saying ‘No, don’t get up!’ By occupation as assistant conservation officer, as well as by inclination, I was firmly in the working-class camp at the British Museum, and it was even more fun than Bristol, if less risky.

This was before there were any professional qualifications for organics conservation, which was what we were mostly doing. Again, the workshop (not yet a laboratory) was in the basement of the East Residence wing of the museum, named because it originally housed museum staff, in a cluster of rooms down a long passage. I had a bench in the main room, with Conservation Officers John Lee at the other end and Tom Govier in a small room of his own next door. The senior conservation officers in a room beyond that were older men who had been at the British Museum since before the War. Les Langton would go on about what we youngsters would not have got away with if we had been under him in the Navy, while Harold Gowers was mild and avuncular and more independent minded. They didn’t really like each other. Then there were the museum assistants who did the fetching carrying and storing of artefacts in the warren of vaulted tunnels and pokey rooms under the ground floor galleries, and the carpenter and handyman who made fixtures and fittings. They all took their tea breaks with us in the main conservation workshop on accustomed chairs and stools, and more often than not the banter focused on Senior Museum Assistant Albert Davis.

Albert must have been about fifty, lanky in a dark suit with a gaunt face and toothy quizzical smile. He would sit on a stool in the middle of the room, teasing all of us until, at a signal, everyone would screw up their paper sandwich bags and bombard him with them. The joke was that he was Jewish, but only because his wife worked for a Jewish dry cleaners, and he played to the stereotype, pretending to be tight-fisted. He also smoked like a chimney and his car was said to be an ashtray on wheels. Of various more or less tasteless Jewish jokes played on him, the best was when they made him a seven-branch cigarette holder, of silver-plated copper tubing.

We also had fun with Albert’s tea things. He kept his cup and saucer in a cupboard in Tom’s small room and left his lunchtime cheese roll there every day. I had the idea of putting a square of thick polythene under the slice of cheese, so when he bit into it his teeth wouldn’t go through. He enjoyed that joke and every day afterwards he would make a show of lifting the cheese to check underneath it before eating. So I cut a slice of tough yellow beeswax and substituted it for the cheese, he went through the usual pantomime, took a bite and couldn’t get his teeth through the wax, just leaving a row of tooth marks. He enjoyed that too, so we tried something else. With the help of our boss Harold Gowers, we tried to drill a hole in the bottom of Albert’s teacup, but unfortunately it split in two, so I repaired it with water-soluble glue. When Albert had his tea, it should have fallen in half but instead it stayed together above the tea-line and just opened up at the bottom, filling the saucer with tea – less dramatic but still amusing.

Mick Goddard, Museum Assistant for Africa and about thirty years old, was the most ingenious of the practical jokers, and later the creator of many practical inventions for the Department. He was very good at creeping up behind you when you were concentrating on repairs to an African or Polynesian artefact and dropping a large iron bin or slapping a plank on the floor with his foot. I never managed to catch him out in the same way. Perhaps his best stunt was a booby trap which he set up after work to catch Tom in his room the next morning. Unfortunately, it caught one of the security warders on his night-time patrol instead. As the poor man opened Tom’s door, a huge block of expanded polystyrene fell on his head, the bin fell with a clang on the floor, and his torch lit up the naked figure of a shop window dummy standing in the middle of the room.

I doubt if the senior staff of the Department, in their offices on the second floor of the east wing galleries, had any idea of what was going on in the basement. The Keeper, Adrian Digby, was a Central America archaeologist, a kindly old bloke but very formal. Every few weeks he would come down to our workshop, jingling his keys in front of him with both hands and looking over his half-moon glasses as he asked questions on the lines of ‘How’s it going Burt? Finding the job interesting?’ He was ‘Mr Digby’ to me, and ‘Sir’ to Les Langton, who was a typical NCO. More than twenty years later, when Digby returned for exhibition openings where hardly anyone remembered him and I kept him company, he told me the story of how, when the collections and staff were evacuated during the War, ‘Langton’ asked if he had seen ‘his other wife’s shoe’, meaning his wife’s other shoe. He found this amusing enough to tell me more than once. The other senior curators were rather less formal and called me Ben, but to me they were still ‘Mr (Bryan) Cranstone’, Assistant Keeper for Oceania, ‘Miss (Elizabeth) Carmichael’, Assistant Keeper for the Americas, ‘Miss (Shelagh) Weir’, Assistant Keeper for Asia and Europe, and ‘Mr (William) Fagg’, Deputy Keeper. Bill Fagg, a distinguished African art historian, was the most difficult to get to know, partly because he spoke so slowly that you wanted to finish his sentences for him, but also probably because he was shy. I later heard that there were tensions between Digby and Fagg, but this was not apparent to the junior staff.

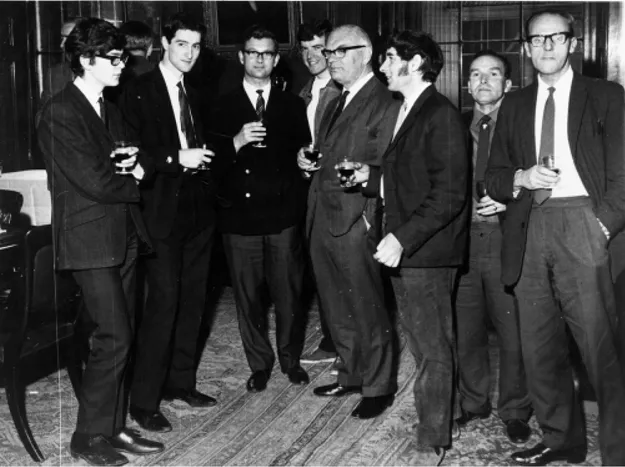

Figure 1.1. ‘Ethno’ staff at Adrian Digby’s retirement party in 1969: left to right, Ben Burt, Assistant Conservation Officer; Tom Govier and John Lee, Conservation Officers; Dave Osborn, handyman; Bill Fagg, Deputy Keeper; Mick Goddard, Museum Assistant; Sid Hunter, Carpenter; and Harry Cousins, Museum Assistant. (© Trustees of the British Museum.)

The gap between the basement and the upstairs offices was an apt symbol for the class structure of the British Museum in those days. The only time I remember the keepers noticing any untoward behaviour was when the handyman, Dave Osborne, was taking pot-shots with an airgun from the basement at pigeons on the roof, and accidentally shot a hole in Mr Digby’s office window on the second floor. I heard that Digby ran out shouting ‘Someone’s trying to kill me!’ Dave was only saved from the sack because his father was head of the carpenters’ shop and interceded with Maisie Webb, the Deputy Director, who he used to do private jobs for.

The British Museum employed mostly men in all kinds of trades and none, and the junior curatorial staff came from similar backgrounds, finding themselves there more or less by accident with no prior interest in museums or their contents. These were working-class jobs where people might remain for life, if they chose, as many did. Parents might be followed into the British Museum by their children, like Dave and his father, or ‘Ron the Painter’ Gazzaniga, who had a son in the locksmiths and a daughter in the bookbinders. But those with the aptitude might move from trades or unskilled work into more interesting jobs with the museum collections. Albert Davis had started as a labourer in the ‘heavy gang’ of masons’ assistants who moved large objects and loads around, before coming to Ethnography as a museum assistant and ending up in charge of the Department’s Stores. Mick Goddard began by fetching books in the Library in 1962, following about twenty unskilled jobs and a spell as an army conscript in Kenya during the Mau Mau rebellion, after leaving school with no qualifications and very dubious spelling. He retired in 1995 as a senior museum assistant doing an artistic technical job which he more or less invented for himself during thirty-five years’ service. In Conservation, Harold Gowers and Les Langton were craftsmen, John Lee had been a British Museum photographer, and Tom Govier a British Museum locksmith.

In those days, everyone was learning on the job and, while some never learned very much, others had the opportunity to develop new skills and interests. However, without university degrees they could not hope to move into the academic grades in the British Museum. Denis Alsford, who first joined his uncle in the locksmiths, became a museum assistant in Ethnography and a self-taught expert on Amazonian Indians, but he had to go to Canada to get academic recognition, soon becoming Curator of Collections in the National Museum of Man. Tom Govier later joined him there, to become Head of Conservation. Not all were as well suited to their jobs, including the clumsy museum assistant who accidentally kicked the ear off a famous ancient Mexican onyx jaguar. Others just worked steadily and conscientiously without academic ambition until they became indispensable experts on where and how the collections were stored. John Osborn joined the British Museum as a photocopier straight from school in 1964, became a museum assistant in Ethnography in 1966 and eventually retired as Albert’s successor in charge of the Stores in 2009. Then there was Ted the Messenger, a bent and wizened old ex-soldier in a khaki overall who had his own chair and cupboard in the passage where he made his tea and boiled his eggs for lunch in the same kettle and grumbled at everyone. He was one of those people who made life miserable for himself by trying to make it miserable for everyone else. Once, when Mick had dressed a dummy in a white lab coat and wire-wool hair to stand with its back turned at Harold Gowers’ workbench, Ted walked in and began speaking to it, to everyone’s amusement but his own. Nor was Ted amused when someone who saw him and Albert pushing a barrow of artefacts through a gallery was reminded of a popular TV comedy series about rag and bone men and called out ‘Steptoe and Son!’

While the academic staff of the Department had to deal with the scholarly legacy of primitivism to curate the artefacts of the ‘savage and barbarous peoples’, their juniors had the casual racism of British popular culture to enliven tea break conversations in the conservation workshop. Geoff was a carpenter in his thirties who rode a BMW motorbike with a sidecar and was often told he was using a racehorse ...